2. 南京医科大学附属苏州医院重症医学科(苏州市立医院重症医学科),苏州 215000

2. Department of Critical Care Medicine, The Affiliated Suzhou Hospital of Nanjing Medical University (Department of Critical Care Medicine, Suzhou Municipal Hospital), Suzhou 215000, China

脓毒症是由于宿主对感染的反应失调引起的严重器官功能障碍[1],具有较高的病死率,尽管随着医学的进步,病死率有所下降,但脓毒症相关死亡仍占据了全球所有死亡人数的19.7%[2]。谵妄是一种脑病,其特征是警觉性和注意力的急性改变,在短时间内出现认知障碍[3]。多达17.7%~48.0%的ICU患者会发生谵妄[4],并且ICU谵妄在脓毒症患者中更为常见[5]。

谵妄与病死率增加有关[4, 6],脓毒症相关谵妄也与脓毒症患者ICU 28 d病死率增加相关[7],因此确定具有短期病死率高风险的脓毒症相关谵妄患者的预后具有重要意义。目前已经开发了脓毒症相关脑病(sepsis-associated encephalopathy, SAE)预后的相关模型[8-9],但脓毒症相关谵妄作为一个新的概念,其排除了SAE中昏迷的患者[10],该类患者的预后预测模型未见报道。

列线图可以细化每个预测因子的分数,以评估患者死亡的概率,是一种简单的统计可视化工具,近年来被广泛用于预测疾病的发生、发展、预后和生存[11-12]。本研究通过医学信息市场重症监护数据库-Ⅲ(Medical Information Mart for Intensive Care Ⅲ, MIMIC-Ⅲ)数据库数据建立脓毒症相关谵妄患者预后预测模型,构建列线图,并使用嘉兴市第一医院的数据进行外部验证,在临床实践中,可以识别出28 d死亡风险较高的脓毒症相关谵妄患者,对于脓毒症相关谵妄患者的后续决策,治疗和重症监护具有重要价值。

1 资料与方法 1.1 研究对象本研究内部验证数据来自MIMIC-Ⅲ数据库,数据来自贝丝以色列女执事医疗中心重症监护室,包含2001年至2012年在ICU住院患者的临床数据。运用Navicat软件,根据国际疾病分类第九版诊断编码从MIMIC-Ⅲ数据库中提取首次入住ICU的成年脓毒症患者,从中筛选出合并谵妄的患者。本研究成员已取得数据库的授权(证书编号:46429516)。同时回顾性收集嘉兴市第一医院2021年1月至2022年9月收治的符合脓毒症相关谵妄的患者临床资料。入选标准:(1)年龄≥18岁;(2)首次入住ICU;(3)住ICU时间 > 24 h;(4)符合脓毒症诊断;(5)采用CAM-ICU工具进行谵妄筛查符合谵妄诊断。排除标准:(1)有原发性脑损伤(颅脑外伤、脑出血、缺血性脑卒中、癫痫,或颅内感染及其他脑血管病)患者;(2)精神障碍和神经系统疾病患者;(3)长期酗酒或吸毒;(4)代谢性脑病、肝性脑病、高血压性脑病、低血糖性昏迷及影响意识的肝病或肾病患者;(5)PaCO2≥80 mmHg(1 mmHg=0.133 kPa);(6)数据缺失患者。本研究已通过嘉兴市第一医院医学伦理委员会批准(伦理编号:2022-KY-590)。

1.2 研究分组将MIMIC-Ⅲ数据库中的脓毒症相关谵妄患者作为建模组,根据28 d是否死亡分为存活组和死亡组。嘉兴市第一医院收集的脓毒症相关谵妄患者作为验证组。

1.3 研究方法提取患者的一般资料,包括年龄、性别、生命体征:心率、平均动脉压、呼吸频率、氧饱和度(均为入ICU 24 h内平均值);实验室指标,包括血糖、尿素氮、肌酐、钠离子、钾离子、乳酸、血红蛋白、白细胞计数、血小板计数、红细胞压积,均为入ICU后首次化验结果。以及机械通气(入ICU时)、序贯器官功能衰竭评分(sequential organ failure assessment, SOFA)(入ICU时);既往史:心血管疾病、高血压、糖尿病。嘉兴市第一医院与MIMIC-Ⅲ数据库提取的数据内容及时间节点均相同。

1.4 统计学方法对数据采用SPSS 21.0软件及“R”语言(4.2.1)进行统计分析。符合正态分布的计量资料,采用均数±标准差(x±s)表示,组间采用独立样本t检验,计量资料为非正态分布,用中位数(四分位数)[M(Q1,Q3)]表示,组间采用Mann-Whitney U检验。计数资料以频数(%)表示,比较采用卡方检验或Fisher精确检验。单因素差异有统计学意义的因素采用多因素Logistic回归(逐步向前法)得出独立影响因素。本研究分为建模组和验证组,通过建模组构建预测模型,并绘制列线图,并通过验证组进行外部验证。通过绘制受试者工作特征(receiver operating characteristic, ROC)曲线、校准图以及决策曲线(decision curve analysis, DCA)对模型的区分度、校准度、净获益进行评价。以P < 0.05表示差异有统计学意义。

2 结果 2.1 患者基本临床资料在建模组中,根据纳入及排除标准从MIMIC-Ⅲ数据库获得250例患者的临床资料。在验证组中,来自嘉兴市第一医院的154例患者用于外部验证。两组在年龄、心率、平均动脉压、尿素氮、钾离子、乳酸、白细胞计数、血小板计数、机械通气、SOFA评分、心血管疾病、糖尿病方面差异有统计学意义(均P < 0.05),见表 1。

| 指标 | 建模组(n=250) | 验证组(n=154) | 统计值 | P值 |

| 一般情况 | ||||

| 年龄(岁)a | 67.00 (57.00, 78.75) | 72.00 (66.00, 81.00) | -2.699 | 0.007 |

| 男性b | 141 (56.4) | 101 (65.6) | 3.347 | 0.067 |

| 生命体征a | ||||

| 心率(次/min) | 89.00 (76.25, 102.75) | 101.00 (90.00, 114.00) | -6.525 | < 0.001 |

| 平均动脉压(mmHg) | 73.00 (67.00, 80.00) | 64.00 (60.00, 83.75) | -3.837 | < 0.001 |

| 呼吸频率(次/min) | 20.00 (17.00, 23.00) | 20.00 (17.00, 24.00) | -0.937 | 0.349 |

| 氧饱和度(%) | 98.00 (96.00, 99.00) | 97.00 (94.00, 100.00) | -1.125 | 0.261 |

| 实验室检查 | ||||

| 血糖(mmol/L)a | 7.72 (6.34, 9.51) | 7.40 (6.00, 10.07) | -0.647 | 0.517 |

| 尿素氮(mmol/L)a | 9.64 (6.07, 16.33) | 11.68 (7.64, 17.31) | -2.469 | 0.014 |

| 肌酐(µmol/L)a | 123.76 (79.56, 203.32) | 135.25 (78.45, 239.50) | -0.726 | 0.468 |

| 钠离子(mmol/L)a | 137.00 (134.00, 140.00) | 136.95 (133.00, 140.15) | -1.074 | 0.283 |

| 钾离子(mmol/L)a | 4.40 (3.90, 4.80) | 3.80 (3.40, 4.30) | -6.254 | < 0.001 |

| 乳酸(mmol/L)a | 1.80 (1.30, 3.00) | 2.30 (1.30, 4.10) | -2.058 | 0.039 |

| 血红蛋白(g/L)a | 110.00 (93.00, 127.75) | 108.00 (94.00, 124.00) | -0.289 | 0.773 |

| 白细胞计数(×109/L)a | 12.70 (8.30, 17.50) | 10.12 (6.29, 15.04) | -3.373 | 0.001 |

| 血小板计数(×109/L)a | 208.00 (140.25, 288.50) | 131.50 (76.75, 192.75) | -6.863 | < 0.001 |

| 红细胞压积(%)a | 0.34 (0.29, 0.39) | 0.33 (0.28, 0.37) | -1.251 | 0.211 |

| 机械通气b | 185 (74.0) | 37 (24.0) | 96.141 | < 0.001 |

| 评分 | ||||

| SOFA评分a | 7.00 (4.00, 10.00) | 6.00 (4.00, 9.00) | -2.190 | 0.029 |

| 既往史b | ||||

| 心血管疾病 | 178 (71.2) | 33 (21.4) | 94.616 | < 0.001 |

| 高血压 | 173 (69.2) | 96 (62.3) | 2.017 | 0.156 |

| 糖尿病 | 88 (35.2) | 36 (23.4) | 6.262 | 0.012 |

| 28 d病死率b | 65 (26.0) | 42 (27.3) | 0.079 | 0.778 |

| 注:SOFA评分为序贯器官功能衰竭评分;a为M(Q1,Q3),b为(例,%) | ||||

根据28 d是否存活,MIMIC-Ⅲ数据库的185例(185/250,74%)患者为存活组,65例(65/250,26%)患者为死亡组。两组在性别、心率、平均动脉压、氧饱和度、血糖、钠离子、钾离子、白细胞计数、红细胞压积、机械通气、高血压、糖尿病差异无统计学意义(P > 0.05),而两组在年龄、呼吸频率、尿素氮、肌酐、乳酸、血红蛋白、血小板计数、SOFA评分、心血管疾病方面差异有统计学意义(P < 0.05),见表 2。

| 指标 | 存活组(n=185) | 死亡组(n=65) | 统计值 | P值 |

| 一般情况 | ||||

| 年龄(岁)a | 66.00(56.00, 76.00) | 76.00(66.00, 85.00) | -3.914 | < 0.001 |

| 男性b | 106(57.3) | 35(53.8) | 0.233 | 0.629 |

| 生命体征a | ||||

| 心率(次/min) | 88.00(76.00, 102.00) | 92.00(80.00, 103.00) | -1.217 | 0.223 |

| 平均动脉压(mmHg) | 73.00(68.00, 80.00) | 71.00(67.00, 81.00) | -0.777 | 0.437 |

| 呼吸频率(次/min) | 19.00(17.00, 23.00) | 21.00(19.00, 24.00) | -2.891 | 0.004 |

| 氧饱和度(%) | 98.00(96.00, 99.00) | 97.00(95.00, 98.00) | -1.735 | 0.083 |

| 实验室检查 | ||||

| 血糖(mmol/L)a | 7.66(6.28, 9.54) | 7.92(6.63, 9.13) | -0.308 | 0.758 |

| 尿素氮(mmol/L)a | 8.93(5.71, 15.35) | 12.85(8.21, 21.06) | -3.651 | < 0.001 |

| 肌酐(µmol/L)a | 106.08(79.56, 185.64) | 167.96(97.24, 247.53) | -2.630 | 0.009 |

| 钠离子(mmol/L)a | 137.00(134.00, 141.00) | 137.00(134.00, 140.00) | -0.294 | 0.769 |

| 钾离子(mmol/L)a | 4.30(3.90, 4.80) | 4.50(3.90, 5.20) | -1.588 | 0.112 |

| 乳酸(mmol/L)a | 1.70 (1.20, 2.80) | 2.20 (1.40, 3.50) | -2.007 | 0.045 |

| 血红蛋白(g/L)a | 112.00 (94.00, 130.00) | 98.00 (91.00, 116.00) | -2.685 | 0.007 |

| 白细胞计数(×109/L)a | 12.50 (8.40, 17.30) | 13.00 (8.20, 19.30) | -0.286 | 0.775 |

| 血小板计数(×109/L)a | 218.00 (150.00, 296.00) | 184.00 (110.00, 255.00) | -2.524 | 0.012 |

| 红细胞压积(%)a | 0.35 (0.29, 0.39) | 0.32 (0.28, 0.37) | -1.676 | 0.094 |

| 机械通气b | 142 (76.8) | 43 (66.2) | 2.811 | 0.094 |

| 评分 | ||||

| SOFA评分a | 6.00 (4.00, 9.00) | 9.00 (6.00, 11.00) | -3.496 | < 0.001 |

| 既往史b | ||||

| 心血管疾病 | 124 (67.0) | 54 (83.1) | 6.043 | 0.014 |

| 高血压 | 126 (68.1) | 47 (72.3) | 0.398 | 0.525 |

| 糖尿病 | 68 (36.8) | 20 (30.8) | 0.756 | 0.385 |

| 注:SOFA评分为序贯器官功能衰竭评分;a为M(Q1,Q3),b为(例,%) | ||||

纳入上述基本临床资料中差异有统计学意义的变量,运用多因素Logistic回归分析发现,年龄、呼吸频率、乳酸、血红蛋白、SOFA评分是脓毒症相关谵妄患者28 d死亡的独立预测因素。结果如下:年龄(OR=1.057,95%CI: 1.030~1.084,P < 0.001),呼吸频率(OR=1.117,95%CI: 1.037~1.202,P=0.003),乳酸(OR=1.137,95%CI: 1.011~1.279,P=0.032),血红蛋白(OR=0.983,95%CI: 0.970~0.997,P=0.020),SOFA评分(OR=1.184,95%CI: 1.070~1.309,P=0.001),见表 3。

| 指标 | 回归系数 | 标准误 | Wald | P值 | OR值 | 95%CI |

| 年龄 | 0.055 | 0.013 | 18.297 | < 0.001 | 1.057 | 1.030~1.084 |

| 呼吸频率 | 0.110 | 0.038 | 8.603 | 0.003 | 1.117 | 1.037~1.202 |

| 乳酸 | 0.129 | 0.060 | 4.603 | 0.032 | 1.137 | 1.011~1.279 |

| 血红蛋白 | -0.017 | 0.007 | 5.456 | 0.020 | 0.983 | 0.970~0.997 |

| SOFA评分 | 0.168 | 0.051 | 10.743 | 0.001 | 1.184 | 1.070~1.309 |

| 常数 | -7.024 | 1.629 | 18.599 | < 0.001 | 0.001 |

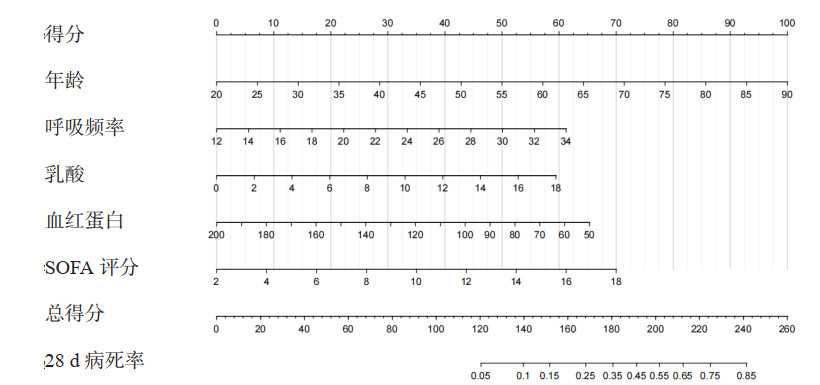

根据上述5个独立预测因素,建立脓毒症相关谵妄预后预测模型Logit (P)= -7.024+0.055×年龄+0.110×呼吸频率+0.129×乳酸-0.017×血红蛋白+0.168×SOFA评分。使用R语言绘制列线图,综合各因素的得分以计算总分,可得出脓毒症相关谵妄28 d死亡的概率,见图 1。Hosmer-Lemeshow检验显示,建模组(χ2=3.795,P=0.875)和验证组(χ2=7.459,P=0.488)均表明该模型拟合效果较好。

|

| 图 1 预测脓毒症相关谵妄患者28 d死亡的列线图 Fig 1 Nomogram for predicting 28-day mortality of patients with SAD |

|

|

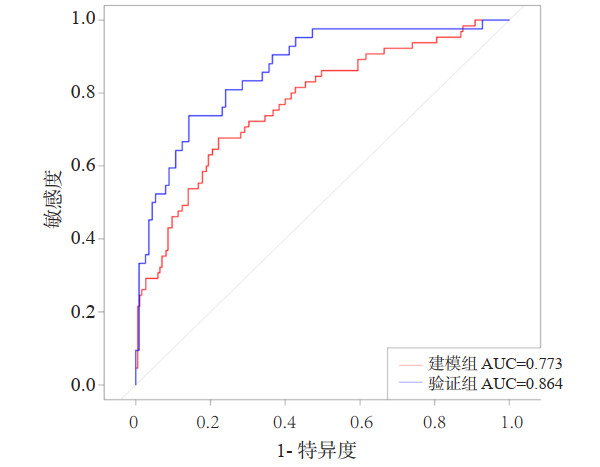

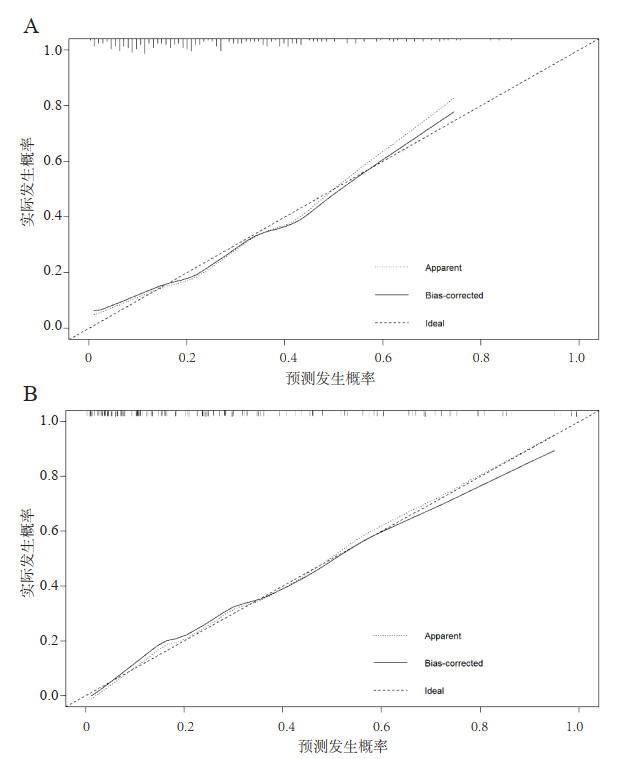

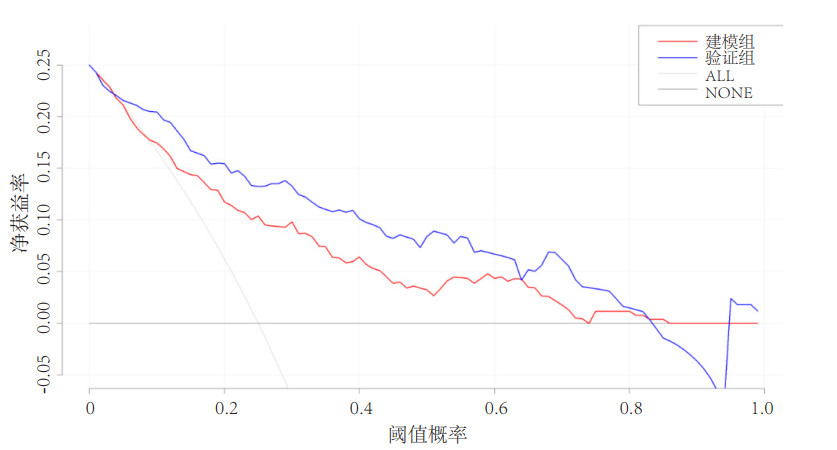

在建模组中,列线图的曲线下面积(AUC)为0.773(95%CI: 0.705~0.841)(图 2),校准曲线接近理想的对角线(P=0.875)(图 3A)。此外,DCA在预测模型中表现出较好的净获益(图 4)。运用嘉兴市第一医院的154例患者进行外部验证,检验该列线图,AUC为0.864(95%CI: 0.799~0.928)(图 2),反映了列线图的良好准确性。同时,该模型具有良好的一致性,验证组的校准曲线也接近于理想的对角线(P=0.488)(图 3B),并同样表现出较好的净获益(图 4)。

|

| 图 2 建模组和验证组中预测模型的受试者工作特征(ROC)曲线 Fig 2 ROC curve of prediction model between the training and validation cohorts |

|

|

|

| 图 3 建模组(A)和验证组(B)中列线图模型的校准曲线 Fig 3 Calibration curve of nomogram between the training(A) and validation(B) cohorts |

|

|

|

| 图 4 建模组和验证组中列线图模型的决策曲线 Fig 4 Decision curve of nomogram between the training and validation cohorts |

|

|

本研究显示,建模组中26%的脓毒症相关谵妄患者和验证组中27.3%的患者28 d死亡。基于多因素Logistic回归分析发现,年龄、呼吸频率、乳酸、血红蛋白、SOFA评分与脓毒症相关谵妄患者28 d死亡显著相关。据本团队所知,尚无预测模型来预测脓毒症相关谵妄患者的预后,本研究构建的列线图模型为脓毒症相关谵妄患者早期预警和干预提供了一种简单且相对准确的风险识别工具。

既往研究得出,年龄是脓毒症死亡的独立预测因素[13],病死率随着年龄的增加而增加,并且在71~77岁之间,病死率的增加率最大[14]。本研究得出,年龄是脓毒症相关谵妄患者28 d死亡的独立预测因素,且年龄与患者病死率呈正相关。这与之前关于SAE的研究结果一致[15],这可能与高龄可能与更多的共存疾病、免疫应答受损、营养不良等因素相关。同时,伴有基础疾病的重症患者往往进展较快,预后较差。特别是合并高血压、糖尿病、急性肾损伤和慢性阻塞性肺疾病的患者,这些患者可能更容易发生中枢神经系统并发症[16-19]。

呼吸频率已被许多危重病预测评分系统用作预测因子,如qSOFA[20]以及APACHE Ⅱ评分等。回顾性研究提示,呼吸频率是脓毒症患者预后不良的预测因素[21],也是SAE 30 d死亡的独立预测因素[8]。正常大脑功能的维持即需要高度依赖氧气和营养物质,谵妄患者的脑功能活跃,代谢产物更多,为防止神经功能的损害机体则会代偿性地加强通气和营养物质消耗[22],合并脓毒症时,呼吸驱动进一步增强,进而导致呼吸频率增加,导致脓毒症相关谵妄患者病死率增加。

血清乳酸升高是器官灌注不足的表现,脓毒症引起组织缺氧和线粒体功能障碍时,丙酮酸迅速积累,通过代谢引起高乳酸血症。根据最新的定义,乳酸升高是Sepsis-3脓毒性休克定义的一部分[23],乳酸是判断脓毒症严重程度的重要标志物之一。2020年一项回顾性研究显示,乳酸升高是SAE 30 d死亡的独立危险因素[8],并且乳酸已被用于脓毒症相关谵妄的预测,乳酸的蓄积导致的代谢性酸中毒可能会进一步加重脑代谢功能障碍,导致脓毒症相关谵妄患者病情进一步加重,从而影响患者的预后。

脓毒症常导致需氧量增加,并发谵妄则会进一步增加需氧量,而血红蛋白降低导致氧输送减少,进一步加重脓毒症患者组织缺氧,导致器官功能障碍加剧。血红蛋白是脓毒症患者短期和长期预后的独立预测因素[24-25]。本研究提示血红蛋白与脓毒症相关谵妄患者28 d病死率呈负相关,对于脓毒症相关谵妄患者输注红细胞的研究未见报道,本团队将在后续研究中探索输注红细胞能否改善脓毒症相关谵妄患者这一特定亚组的预后。

SOFA评分最初设计用于序贯评估脓毒症所致危重症患者器官功能障碍的严重程度[26],其中包含了对神经功能的评估,即格拉斯哥昏迷评分。目前SOFA评分已广泛运用于重症监护室,并且易于获得。有研究得出,SOFA评分每增加1分,脓毒症患者平均病死率增加1.8%~3.3%[27]。SOFA评分也是老年SAE患者病死率增加的独立预测指标[28]。SOFA评分越高,提示脓毒症相关谵妄患者器官功能障碍越严重,病死率越高。

本研究仍存在一些不足:(1)本研究样本量较少;(2)本研究为回顾性研究,可能存在一定程度的内部偏倚;(3)MIMIC-Ⅲ数据库仅包含2001年至2012年的患者数据,无法获取部分实验室检测结果,如铁蛋白、免疫学指标等,因此一些潜在的预测因素没有进行评估,本团队将在接下来的研究中研究更多的潜在指标,建立更准确的预测模型;(4)本研究仅纳入了入院24 h内的指标,未纳入动态指标。

本研究中,年龄、呼吸频率、乳酸、血红蛋白、SOFA评分是脓毒症相关谵妄患者28 d死亡的独立预测因素,由此构建的列线图为ICU医生提供了一个简单且直观的工具以预测脓毒症相关谵妄患者的预后,可以帮助临床医生评估患者情况,以此做出临床决策,可能对患者预后产生积极影响。

利益冲突 所有作者声明无利益冲突

作者贡献声明 柏晓奇、顾琼:数据收集及整理、论文撰写;许俊、郁慧杰:研究设计、统计分析、论文修改

| [1] | van der Poll T, Shankar-Hari M, Wiersinga WJ. The immunology of sepsis[J]. Immunity, 2021, 54(11): 2450-2464. DOI:10.1016/j.immuni.2021.10.012 |

| [2] | Rudd KE, Johnson SC, Agesa KM, et al. Global, regional, and national sepsis incidence and mortality, 1990-2017: analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study[J]. Lancet, 2020, 395(10219): 200-211. DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(19)32989-7 |

| [3] | Slooter AJC, Otte WM, Devlin JW, et al. Updated nomenclature of delirium and acute encephalopathy: statement of ten Societies[J]. Intensive Care Med, 2020, 46(5): 1020-1022. DOI:10.1007/s00134-019-05907-4 |

| [4] | Zhang Y, Hu JJ, Hua TF, et al. Development of a machine learning-based prediction model for sepsis-associated delirium in the intensive care unit[J]. Sci Rep, 2023, 13(1): 12697. DOI:10.1038/s41598-023-38650-4 |

| [5] | Brück E, Schandl A, Bottai M, et al. The impact of sepsis, delirium, and psychological distress on self-rated cognitive function in ICU survivors-a prospective cohort study[J]. J Intensive Care, 2018, 6: 2. DOI:10.1186/s40560-017-0272-6 |

| [6] | Pauley E, Lishmanov A, Schumann S, et al. Delirium is a robust predictor of morbidity and mortality among critically ill patients treated in the cardiac intensive care unit[J]. Am Heart J, 2015, 170(1) 79-86, 86.e1. DOI:10.1016/j.ahj.2015.04.013 |

| [7] | Lei W, Ren ZY, Su J, et al. Immunological risk factors for sepsis-associated delirium and mortality in ICU patients[J]. Front Immunol, 2022, 13: 940779. DOI:10.3389/fimmu.2022.940779 |

| [8] | Yang Y, Liang SR, Geng J, et al. Development of a nomogram to predict 30-day mortality of patients with sepsis-associated encephalopathy: a retrospective cohort study[J]. J Intensive Care, 2020, 8: 45. DOI:10.1186/s40560-020-00459-y |

| [9] | Peng LW, Peng C, Yang F, et al. Machine learning approach for the prediction of 30-day mortality in patients with sepsis-associated encephalopathy[J]. BMC Med Res Methodol, 2022, 22(1): 183. DOI:10.1186/s12874-022-01664-z |

| [10] | Tsuruta R, Oda Y. A clinical perspective of sepsis-associated delirium[J]. J Intensive Care, 2016, 4: 18. DOI:10.1186/s40560-016-0145-4 |

| [11] | 白丽爽, 王兴义, 杨立山. 多发伤患者并发脓毒血症风险的列线图模型构建[J]. 中华急诊医学杂志, 2024, 33(1): 65-69. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.issn.1671-0282.2024.01.011 |

| [12] | 查皓宇, 谭睿, 王浩楠, 等. 儿童重症细菌感染死亡风险预测模型的建立及评价[J]. 中华急诊医学杂志, 2023, 32(4): 489-496. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.issn.1671-0282.2023.04.009 |

| [13] | Martin GS, Mannino DM, Moss M. The effect of age on the development and outcome of adult sepsis[J]. Crit Care Med, 2006, 34(1): 15-21. DOI:10.1097/01.ccm.0000194535.82812.ba |

| [14] | Kotfis K, Wittebole X, Jaschinski U, et al. A worldwide perspective of sepsis epidemiology and survival according to age: Observational data from the ICON audit[J]. J Crit Care, 2019, 51: 122-132. DOI:10.1016/j.jcrc.2019.02.015 |

| [15] | Chen JY, Shi XB, Diao MY, et al. A retrospective study of sepsis-associated encephalopathy: epidemiology, clinical features and adverse outcomes[J]. BMC Emerg Med, 2020, 20(1): 77. DOI:10.1186/s12873-020-00374-3 |

| [16] | Sonneville R, de Montmollin E, Poujade J, et al. Potentially modifiable factors contributing to sepsis-associated encephalopathy[J]. Intensive Care Med, 2017, 43(8): 1075-1084. DOI:10.1007/s00134-017-4807-z |

| [17] | Hajjar I, Keown M, Frost B. Antihypertensive agents for aging patients who are at risk for cognitive dysfunction[J]. Curr Hypertens Rep, 2005, 7(6): 466-473. DOI:10.1007/s11906-005-0043-y |

| [18] | Sonneville R, Vanhorebeek I, den Hertog HM, et al. Critical illness-induced dysglycemia and the brain[J]. Intensive Care Med, 2015, 41(2): 192-202. DOI:10.1007/s00134-014-3577-0 |

| [19] | Siew ED, Fissell WH, Tripp CM, et al. Acute kidney injury as a risk factor for delirium and Coma during critical illness[J]. Am J Respir Crit Care Med, 2017, 195(12): 1597-1607. DOI:10.1164/rccm.201603-0476OC |

| [20] | Seymour CW, Liu VX, Iwashyna TJ, et al. Assessment of clinical criteria for sepsis: for the third international consensus definitions for sepsis and septic shock (sepsis-3)[J]. JAMA, 2016, 315(8): 762-774. DOI:10.1001/jama.2016.0288 |

| [21] | Weng J, Hou RN, Zhou XM, et al. Development and validation of a score to predict mortality in ICU patients with sepsis: a multicenter retrospective study[J]. J Transl Med, 2021, 19(1): 322. DOI:10.1186/s12967-021-03005-y |

| [22] | Holla VV, Prasad S, Pal PK. Neurological effects of respiratory dysfunction[J]. Handb Clin Neurol, 2022, 189: 309-329. DOI:10.1016/B978-0-323-91532-8.00001-X |

| [23] | Shankar-Hari M, Phillips GS, Levy ML, et al. Developing a new definition and assessing new clinical criteria for septic shock: for the third international consensus definitions for sepsis and septic shock (sepsis-3)[J]. JAMA, 2016, 315(8): 775-787. DOI:10.1001/jama.2016.0289 |

| [24] | Muady GF, Bitterman H, Laor A, et al. Hemoglobin levels and blood transfusion in patients with sepsis in Internal Medicine Departments[J]. BMC Infect Dis, 2016, 16(1): 569. DOI:10.1186/s12879-016-1882-7 |

| [25] | Zhao LN, Zhao LJ, Wang YY, et al. Platelets as a prognostic marker for sepsis: a cohort study from the MIMIC-Ⅲ database[J]. Medicine, 2020, 99(45): e23151. DOI:10.1097/MD.0000000000023151 |

| [26] | Vincent JL, de Mendonça A, Cantraine F, et al. Use of the SOFA score to assess the incidence of organ dysfunction/failure in intensive care units: results of a multicenter, prospective study. Working group on "sepsis-related problems" of the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine[J]. Crit Care Me, 1998, 26(11): 1793-1800. DOI:10.1097/00003246-199811000-00016 |

| [27] | Bauer M, Gerlach H, Vogelmann T, et al. Mortality in sepsis and septic shock in Europe, North America and Australia between 2009 and 2019- results from a systematic review and meta-analysis[J]. Crit Care, 2020, 24(1): 239. DOI:10.1186/s13054-020-02950-2 |

| [28] | Jin GY, Wang SY, Chen JY, et al. Identification of sepsis-associated encephalopathy risk factors in elderly patients: a retrospective observational cohort study[J]. Turk J Med Sci, 2022, 52(5): 1513-1522. DOI:10.55730/1300-0144.5491 |

2024, Vol. 33

2024, Vol. 33