急性上消化道出血(upper gastrointestinal bleeding, UGIB)是急诊常见的急危重症之一, 成年人每年发病率为(100~180)/10万,病死率为2%~15%[1],上消化道大出血患者病死率较UGIB更高[2]。其中肝硬化患者急性UGIB的病死率明显增高[3],而静脉曲张出血患者约占70%[4]。因此,在急诊室进行准确的风险评估及干预对危及生命的消化道出血患者是非常重要的[5]。但临床目前暂无敏感度、特异度高,创伤又小的预测手段。列线图预测模型能够非常直白的显示发生某种疾病的可能性,它是由多元回归分析得出的危险因素绘制而成[6],因此易于临床快速高效的筛选高危患者,并采取及时有效的干预措施。本研究目的是根据常规收集的临床指标和不同评分系统,开发一个列线图预测模型来预测急诊室肝硬化静脉曲张患者发生上消化道大出血的可能性,为临床早期采取干预措施,进行有效治疗提供有效依据。

1 资料与方法 1.1 研究对象本研究为回顾性队列研究,选取宁夏医科大学总医院急诊科2019年10月至2022年10月期间收治的肝硬化食管胃底静脉曲张破裂出血的患者。纳入标准:符合《肝硬化门静脉高压食管胃静脉曲张出血的防治指南》[7]的诊断标准;年龄≥18岁;临床资料完整。排除标准:合并其他病因导致的UGIB(如消化性溃疡、消化系统肿瘤等);合并血液系统、慢性肾脏病或其他部位恶性肿瘤;合并严重的全身性疾病(如重症感染、心脑血管疾病、呼吸系统疾病等);临床资料不完整。研究符合医学伦理学规定,已获得医院伦理委员会批准(伦理审批号:KYLL-2023-0211)。

1.2 研究方法本研究收集(1)一般资料:性别、年龄,入院时的收缩压、舒张压、呼吸、心率、血氧饱和度,是否合并高血压、糖尿病、冠心病、首次出血、经颈静脉肝内门体分流术(transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt, TIPS)后病史等;(2)生化资料:入院第一次血清红细胞计数、红细胞压积、血红蛋白、血小板计数、总胆红素、白蛋白、肌酐、尿素、凝血酶原时间、活化部分凝血酶原时间、凝血酶原国际标准比值、纤维蛋白原定量、D-二聚体定量等;(3)评分资料:MAP (ASH)评分、Glasgow-Blatchford评分(GBS)、AIMS65评分、Child-Pugh分级、ABC评分及终末期肝病模型(model for end-stage liver disease, MELD)评分。

观察结局指标为入院24 h是否发生上消化道大出血。

1.3 统计学方法统计学分析采用SPSS 26.0和R 4.2.2软件进行。计量资料根据是否符合正态分布采用均数±标准差(x±s)或中位数(四分位数)[M(Q1,Q3)]表示,分别使用t检验或非参数Mann-Whitney U检验在组间进行比较。计数资料采用频数(百分数)表示,分析采用χ2或Fisher精确检验。使用随机数字法按照7∶3的比例随机分为建模组与验证组。以建模组数据上消化道大出血作为结局变量,对单因素中差异有统计学意义的因素进一步纳入多因素Logistic回归分析并使用R软件建立列线图预测模型。在两组中对预测模型进行区分度、校准度和临床有效性的验证并比较。以P < 0.05表示差异有统计学意义。

2 结果 2.1 研究对象的临床资料本研究共纳入305例患者,分为建模组215例和验证组90例。对建模组及验证组的一般资料、生化资料及评分资料进行比较(表 1),均差异无统计学意义,两组间具有可比性。

| 指标 | 建模组(n=215) | 验证组(n=90) | t/Z/χ2值 | P值 |

| 一般资料 | ||||

| 男性a | 139(64.7) | 59(65.6) | 0.023 | 0.880 |

| 年龄(岁)b | 55.36±10.92 | 53.59±13.45 | 1.105 | 0.271 |

| 收缩压(mmHg)c | 111(101, 123) | 109(98, 125) | -0.466 | 0.641 |

| 舒张压(mmHg)c | 66(58, 75) | 67(60, 74) | -0.431 | 0.667 |

| 呼吸(次/min)c | 20(19, 21) | 20(18, 20) | -1.075 | 0.282 |

| 心率(次/min)c | 90(80, 105) | 96(82, 110) | -1.357 | 0.175 |

| 血氧饱和度(%)c | 97(96, 98) | 97(96, 98) | -1.035 | 0.300 |

| 高血压a | 28(13.0) | 13(14.4) | 0.110 | 0.740 |

| 糖尿病a | 38(17.7) | 15(16.7) | 0.045 | 0.832 |

| 冠心病a | 11(5.1) | 3(3.3) | 0.143 | 0.705 |

| 首次出血a | 82(38.1) | 35(38.9) | 0.015 | 0.902 |

| TIPS术后a | 19(8.8) | 9(10.0) | 0.103 | 0.748 |

| 生化资料 | ||||

| RBC(×1012/L)b | 2.92±0.81 | 3.00±0.74 | -0.793 | 0.429 |

| HCT(%)c | 24.7(20.6, 27.3) | 25.7(20.5, 30.0) | -0.752 | 0.452 |

| HGB(g/L)c | 79(65, 95) | 85(63, 99) | -0.770 | 0.441 |

| PLT(×109/L)c | 80(56, 114) | 88(65, 133) | -1.266 | 0.205 |

| TBIL(μmom/L)c | 24.0(16.3, 37.9) | 25.9(17.6, 44.4) | -1.285 | 0.199 |

| ALB(g/L) b | 29.53±6.41 | 30.60±6.15 | -1.344 | 0.180 |

| CREA(μmom/L)c | 55.6(46.4, 69.1) | 58.5(50.2, 67.4) | -1.303 | 0.192 |

| UREA(mmom/L)c | 7.79(5.79, 10.23) | 7.85(5.76, 11.03) | -0.383 | 0.702 |

| PT(s) c | 16.1(14.4, 18.3) | 16.2(14.4, 18.6) | -0.078 | 0.938 |

| APTT(s) c | 31.0(28.0, 34.3) | 32.5(28.5, 34.6) | -1.362 | 0.173 |

| INRc | 1.46(1.31, 1.66) | 1.46(1.31, 1.67) | -0.240 | 0.810 |

| FIB(g/L)c | 1.72(1.45, 2.22) | 1.74(1.35, 2.22) | -0.268 | 0.789 |

| D-D(μg/mL)c | 1.10(0.55, 2.31) | 1.00(0.59, 2.75) | -0.896 | 0.370 |

| 评分资料 | ||||

| MAP(ASH)评分c | 2(2, 3) | 2(2, 3) | -0.536 | 0.592 |

| GBS评分c | 11(9, 13) | 11(9, 13) | -0.700 | 0.484 |

| AIMS65评分c | 1(0, 2) | 1(0, 2) | -0.040 | 0.968 |

| Child-Pugh评分c | 7(6, 8) | 7(6, 9) | -0.430 | 0.667 |

| ABC评分c | 4(2, 5) | 4(3, 5) | -0.231 | 0.818 |

| MELD评分b | 7.21±6.06 | 8.17±5.31 | -1.306 | 0.193 |

| 注:TIPS为经颈静脉肝内门体分流术,RBC为红细胞计数,HCT为红细胞压积,HGB为血红蛋白,PLT为血小板计数,TBIL为总胆红素,ALB为白蛋白,CREA为肌酐,UREA为尿素,PT为凝血酶原时间,APTT为活化部分凝血酶原时间,INR为凝血酶原国际标准比值,FIB为纤维蛋白原定量,D-D为D-二聚体定量,MAP(ASH)、GBS、AIMS65、ABC评分均为消化道出血评分,Child-Pugh和MELD评分是评估肝功能的评分;a为例(%),b为x±s,c为M(Q1,Q3) | ||||

建模组中两组患者临床资料比较结果显示,收缩压、舒张压、RBC、HCT、HGB、PLT、TBIL、ALB、CREA、PT、APTT、INR、FIB、D-D、MAP(ASH)评分、GBS评分、AIMS65评分、Child-Pugh评分、ABC评分及MELD评分的差异有统计学意义(均P < 0.05)(见表 2)。将上述分析差异有统计学意义的变量纳入多因素Logistic回归分析结果显示,收缩压、MAP(ASH)评分、Child-Pugh评分及MELD评分是肝硬化静脉曲张上消化道大出血的独立预测因素(见表 3)。

| 指标 | 大出血组(n=43) | 无大出血组(n=172) | t/Z/χ2值 | P值 |

| 一般资料 | ||||

| 男性a | 33(76.7) | 106(61.6) | 3.440 | 0.064 |

| 年龄(岁)b | 57(49, 63) | 55(47, 63) | -0.917 | 0.359 |

| 收缩压(mmHg)b | 102(86, 113) | 113(103, 125) | -4.292 | < 0.001 |

| 舒张压(mmHg)c | 59.88±15.96 | 68.01±11.93 | 3.126 | 0.000 |

| 呼吸(次/min)b | 20(18, 22) | 20(19, 21) | -0.529 | 0.596 |

| 心率(次/min)b | 96(81, 116) | 89(80, 103) | -1.866 | 0.062 |

| 血氧饱和度(%)b | 97(95, 98) | 97(96, 98) | -0.771 | 0.440 |

| 高血压a | 6(14.0) | 22(12.8) | 0.041 | 0.839 |

| 糖尿病a | 9(20.9) | 29(16.9) | 0.392 | 0.531 |

| 冠心病a | 4(9.3) | 7(4.1) | 1.012 | 0.314 |

| 首次出血a | 15(34.9) | 67(39.0) | 0.241 | 0.623 |

| TIPS术后a | 4(9.3) | 15(8.7) | 0.014 | 0.904 |

| 生化资料 | ||||

| RBC(×1012/L)c | 2.43±0.83 | 3.04±0.77 | 4.543 | < 0.001 |

| HCT(%)b | 21.5(16.2, 27.3) | 25.4(21.5, 30.0) | -3.378 | 0.001 |

| HGB(g/L)b | 70(53, 87) | 80(68, 96) | -2.766 | 0.006 |

| PLT(×109/L)b | 67(47, 100) | 84(60, 116) | -2.437 | 0.015 |

| TBIL(μmom/l)b | 32.8(20.1, 49.6) | 21.6(15.5, 34.3) | -2.767 | 0.006 |

| ALB(g/L)c | 23.25±5.70 | 31.10±5.58 | 8.227 | < 0.001 |

| CREA(μmom/l)b | 60.7(47.9, 82.8) | 55.1(45.3, 66.5) | -2.108 | 0.035 |

| UREA(mmom/L)b | 8.01(6.24, 9.63) | 7.78(5.66, 10.34) | -0.500 | 0.617 |

| PT(s)b | 19.9(17.1, 22.5) | 15.7(14.0, 17.4) | -6.489 | < 0.001 |

| APTT(s)b | 35.3(31.2, 41.0) | 30.2(27.5, 33.1) | -5.464 | < 0.001 |

| INRb | 1.80(1.54, 2.03) | 1.43(1.27, 1.57) | -6.331 | < 0.001 |

| FIB(g/L)b | 1.35(1.04, 1.76) | 1.77(1.53, 2.24) | -4.659 | < 0.001 |

| D-D(μg/mL)b | 1.61(0.97, 2.90) | 1.01(0.50, 2.21) | -2.863 | 0.004 |

| 评分资料 | ||||

| MAP(ASH)评分b | 5(3, 6) | 2(2, 3) | -7.065 | < 0.001 |

| GBS评分b | 13(11, 15) | 11(9, 13) | -4.426 | < 0.001 |

| AIMS65评分b | 2(2, 3) | 1(0, 2) | -6.792 | < 0.001 |

| Child-Pugh评分b | 10(8, 11) | 7(6, 8) | -7.679 | < 0.001 |

| ABC评分b | 5(4, 6) | 3(2, 4) | -5.968 | < 0.001 |

| MELD评分c | 12.56±6.28 | 5.87±5.23 | -7.190 | < 0.001 |

| 注:TIPS为经颈静脉肝内门体分流术,RBC为红细胞计数,HCT为红细胞压积,HGB为血红蛋白,PLT为血小板计数,TBIL为总胆红素,ALB为白蛋白,CREA为肌酐,UREA为尿素,PT为凝血酶原时间,APTT为活化部分凝血酶原时间,INR为凝血酶原国际标准比值,FIB为纤维蛋白原定量,D-D为D-二聚体定量,MAP(ASH)、GBS、AIMS65、ABC评分均为消化道出血评分,Child-Pugh和MELD评分是评估肝功能的评分;a为例(%),b为M(Q1,Q3),c为x±s | ||||

| 指标 | B | SE | Wald | OR值 | 95%CI | P值 |

| 收缩压 | -0.086 | 0.033 | 6.668 | 0.918 | 0.860~0.980 | 0.010 |

| MAP(ASH)评分 | 0.690 | 0.343 | 4.037 | 1.993 | 1.017~3.907 | 0.045 |

| Child-Pugh分级 | 0.693 | 0.287 | 5.822 | 1.999 | 1.139~3.510 | 0.016 |

| MELD评分 | 0.335 | 0.153 | 4.818 | 1.398 | 1.037~1.886 | 0.028 |

| 注:MAP(ASH)评分为消化道出血评分,Child-Pugh和MELD评分是评估肝功能的评分 | ||||||

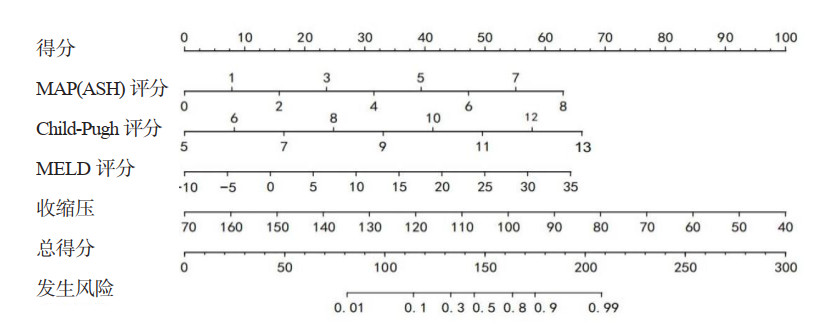

将上述多因素Logistic回归分析结果筛选出的变量纳入列线图预测模型,结局指标选取肝硬化静脉曲张上消化道大出血的发病风险,绘制列线图(图 1)。根据列线图得到每个预测指标对应的分数值,分数值之和被记录为总分,与总分相对应的预测概率是肝硬化静脉曲张上消化道大出血的风险。

|

| MAP(ASH)评分为消化道出血评分,Child-Pugh和MELD评分是评估肝功能的评分 图 1 肝硬化静脉曲张上消化道大出血风险的列线图预测模型 Fig 1 A nomogram prediction model for the risk of cirrhosis variceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding |

|

|

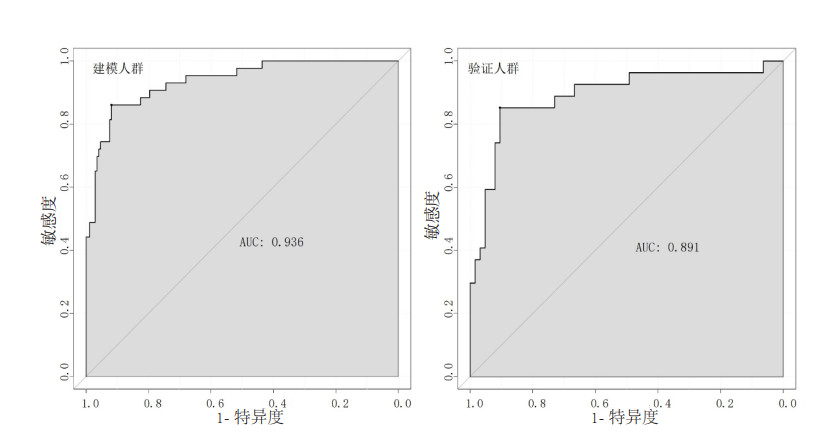

通过绘制两组ROC曲线(图 2),建模组列线图预测模型的AUC为0.936(95%CI: 0.895~0.976),诊断临界值为0.262,敏感度为86.0%,特异度为91.9%。验证组列线图预测模型的AUC为0.891(95%CI: 0.807~0.975),敏感度为85.2%,特异度为90.5%。预测模型在两组中的C指数均 > 0.75。

|

| 图 2 预测模型在建模组和验证组中的ROC Fig 2 ROC of the predicted model in the training group and the validation group |

|

|

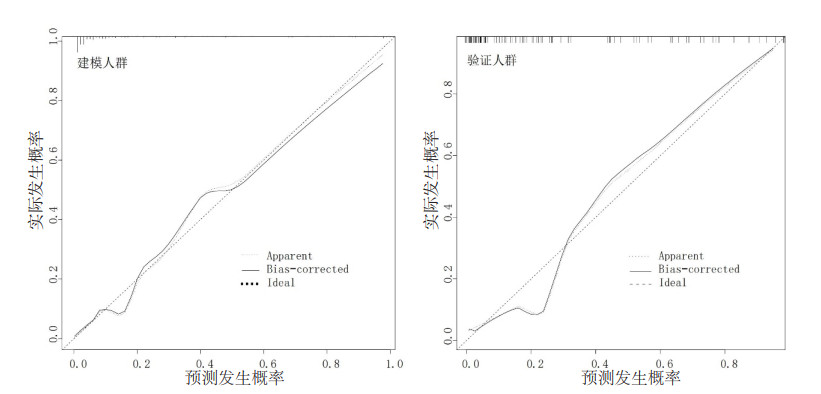

对预测模型在建模与验证组进行Hosmer-Lemeshow检验,预测模型在两组中的Hosmer-Lemeshow检验P值均 > 0.05,差异无统计学意义,表明模型与观察数据吻合较好(图 3)。

|

| 图 3 预测模型在建模组及验证组中的校准曲线 Fig 3 Calibration curves of the prediction model in the training group and the validation group |

|

|

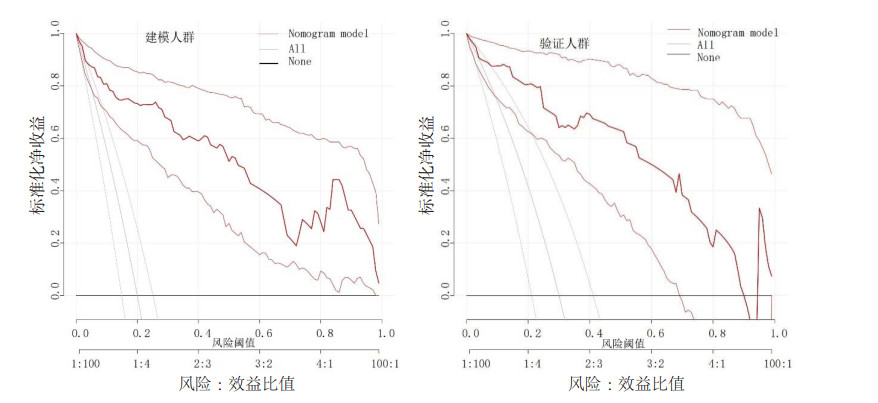

预测模型在建模组及验证组的决策性曲线中显示(图 4):当阈概率分别在8%~99%及10%~90%范围内,患者的净获益比两条极端曲线都高,通过建模组的ROC分析得到的截断值(26.2%)同时在上述两决策性曲线阈概率范围内,因此该模型具有临床有效性。

|

| 图 4 预测模型在建模组及验证组中的决策曲线分析 Fig 4 Decision curve analysis of the prediction model in the training group and the validation group |

|

|

目前临床上评估肝硬化静脉曲张出血危险性的主要工具依然为胃镜[8],曲张静脉的大小和严重度、肝功能情况及红色征的范围是其出血的主要危险因素[9]。虽然急诊内镜检查期间的止血较以前容易,但急诊内镜检查期间可能会发生自发性止血[10]。肝硬化静脉曲张消化道大出血是急诊室较常见的急症,由于它病情变化快、起病又急,并且随时可能危及生命,在某种程度上限制了胃镜在急诊室的早期临床应用。目前的指南对静脉曲张出血进行了最佳处理,但与出血相关的发病率和病死率仍然很高,尤其是在高风险的肝硬化患者中[11]。因此,早期识别并干预急诊室肝硬化静脉曲张消化道大出血高风险的患者尤为重要。

在急诊室中容易计算的简单分数可能会为识别风险较高的患者设定一个“危险信号”。本研究结果发现MAP(ASH)评分、Child-Pugh和MELD评分是肝硬化静脉曲张消化道大出血风险的独立预测因素。MAP(ASH)评分是Redondo-Cerezo等[5]于2020年发表的一个简单的内镜检查前评分。与其他风险评分相比,它在预测UGIB的干预和病死率方面表现出很好的表现,其得益于比较容易计算[12]。另有研究同样指出MAP(ASH)评分在识别需要干预的高风险UGIB患者是非常有用的[13],且在预测干预、再出血和需要ICU入院方面的准确性最高[14]。肝脏疾病的严重程度被认为是肝硬化静脉曲张出血的危险因素之一[9],目前临床常用评估肝功能情况的评分主要为Child-Pugh和MELD评分[15],这两个评分都被认为可以预测肝硬化静脉曲张患者的消化道出血。一些研究认为Child-Pugh在这方面优于MELD评分,而另一些研究则支持MELD评分在预测临床预后方面优于Child-Pugh评分[16]。Peng等[17]研究同样表明Child-Pugh和MELD评分是肝硬化静脉曲张出血风险评估的良好预测指标。在另一项研究中,Child-Pugh和MELD评分被证明是住院结果的自我决定预测因素,而Child-Pugh评分在预测病死率和风险分层方面排名最高[18]。有研究指出,收缩压、舒张压和输血要求是直接反映初始食管胃底静脉曲张出血严重程度的指标,但其与早期再出血无关[19-20]。本研究结果发现入院时的收缩压是肝硬化静脉曲张消化道大出血的独立预测因素。入院时的收缩压 < 100 mmHg(1 mmHg=0.133 kPa)可能反映出血的严重程度[21],同样研究指出收缩压 < 100 mmHg与消化道大出血患者需要输血独立相关[22]。血流动力学不稳定(例如低血压的发生),也可以作为UGIB患者再出血或死亡的预测因素[23]。在既往研究中还发现收缩压 < 100 mmHg这一临界值与预后相关[24-25]。然而必须要注意收缩压不仅可以反映出血的严重程度,还可以反映肝脏疾病的严重程度和伴随的情况。

本研究根据肝硬化静脉曲张患者入院时的临床指标及不同评分系统建立的预测模型,可以预测其发生上消化道大出血的风险概率。将本研究中ROC曲线的临界值26.2%作为决策曲线的阈值时,患者的临床净获益率相对于两种极端方式(不采取干预及全部采取干预)而言均高,这有助于急诊室肝硬化静脉曲张患者的临床决策方案的制定。

综上所述,本研究通过多因素logistic分析发现肝硬化静脉曲张上消化道大出血患者的独立危险因素,并构建了具有良好的鉴别能力、准确性和临床实用性的可视化列线图预测模型,可以用于临床评估。本研究的局限性是来自于一个单中心研究,在一定程度上限制了该预测模型的临床推广使用。

利益冲突 所有作者声明无利益冲突

作者贡献声明 房延儒、王兴义:研究设计、统计学分析、论文撰写和修改;杨立山:研究设计、论文审阅及修改;王聪、虎骁龙:数据收集及整理

| [1] | 中国医师协会急诊医师分会, 中华医学会急诊医学分会, 全军急救医学专业委员会, 等. 急性上消化道出血急诊诊治流程专家共识(2020版)[J]. 中华急诊医学杂志, 2021, 30(1): 15-24. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.issn.1671-0282.2021.01.006 |

| [2] | Redondo-Cerezo E, Tendero-Peinado C, López-Tobaruela JM, et al. Risk factors for massive gastrointestinal bleeding occurrence and mortality: a prospective single-center study[J]. Am J Med Sci, 2024, 367(4): 259-267. DOI:10.1016/j.amjms.2024.01.012 |

| [3] | Zullo A, Soncini M, Bucci C, et al. Clinical outcomes in cirrhotics with variceal or nonvariceal gastrointestinal bleeding: a prospective, multicenter cohort study[J]. J Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2021, 36(11): 3219-3223. DOI:10.1111/jgh.15601 |

| [4] | Songtanin B, Kahathuduwa C, Nugent K. Esophageal stent in acute refractory variceal bleeding: a systematic review and a meta-analysis[J]. J Clin Med, 2024, 13(2): 357. DOI:10.3390/jcm13020357 |

| [5] | Redondo-Cerezo E, Vadillo-Calles F, Stanley AJ, et al. MAP(ASH): a new scoring system for the prediction of intervention and mortality in upper gastrointestinal bleeding[J]. J Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2020, 35(1): 82-89. DOI:10.1111/jgh.14811 |

| [6] | Liu QJ, Xiao JC, Liu L, et al. A new nomogram prediction model for pulmonary embolism in older hospitalized patients[J]. Heliyon, 2024, 10(3): e25317. DOI:10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e25317 |

| [7] | 中华医学会肝病学分会, 中华医学会消化病学分会, 中华医学会消化内镜学分会. 肝硬化门静脉高压食管胃静脉曲张出血的防治指南[J]. 中华内科杂志, 2023, 62(1): 7-22. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.cn501113-20220824-00436 |

| [8] | Hwang JH, Shergill AK, Acosta RD, et al. The role of endoscopy in the management of variceal hemorrhage[J]. Gastrointest Endosc, 2014, 80(2): 221-227. DOI:10.1016/j.gie.2013.07.023 |

| [9] | Garcia-Tsao G, Abraldes JG, Berzigotti A, et al. Portal hypertensive bleeding in cirrhosis: risk stratification, diagnosis, and management: 2016 practice guidance by the American Association for the study of liver diseases[J]. Hepatology, 2017, 65(1): 310-335. DOI:10.1002/hep.28906 |

| [10] | Sasaki Y, Abe T, Kawamura N, et al. Prediction of the need for emergency endoscopic treatment for upper gastrointestinal bleeding and new score model: a retrospective study[J]. BMC Gastroenterol, 2022, 22(1): 337. DOI:10.1186/s12876-022-02413-8 |

| [11] | Kovacs TOG, Jensen DM. Varices: esophageal, gastric, and rectal[J]. Clin Liver Dis, 2019, 23(4): 625-642. DOI:10.1016/j.cld.2019.07.005 |

| [12] | Jimenez-Rosales R, Lopez-Tobaruela JM, Lopez-Vico M, et al. Performance of the new ABC and MAP(ASH) scores in the prediction of relevant outcomes in upper gastrointestinal bleeding[J]. J Clin Med, 2023, 12(3): 1085. DOI:10.3390/jcm12031085 |

| [13] | Stanley AJ, Laine L, Dalton HR, et al. Comparison of risk scoring systems for patients presenting with upper gastrointestinal bleeding: international multicentre prospective study[J]. BMJ, 2017, 356: i6432. DOI:10.1136/bmj.i6432 |

| [14] | Li YJ, Lu Q, Wu KX, et al. Evaluation of six preendoscopy scoring systems to predict outcomes for older adults with upper gastrointestinal bleeding[J]. Gastroenterol Res Pract, 2022, 2022: 9334866. DOI:10.1155/2022/9334866 |

| [15] | Jamil Z, Durrani AA. Assessing the outcome of patients with liver cirrhosis during hospital stay: a comparison of lymphocyte/monocyte ratio with MELD and Child-Pugh scores[J]. Turk J Gastroenterol, 2018, 29(3): 308-315. DOI:10.5152/tjg.2018.17631 |

| [16] | Orloff MJ, Vaida F, Isenberg JI, et al. Child-Turcotte score versus MELD for prognosis in a randomized controlled trial of emergency treatment of bleeding esophageal varices in cirrhosis[J]. J Surg Res, 2012, 178(1): 139-146. DOI:10.1016/j.jss.2012.01.004 |

| [17] | Peng Y, Qi XS, Dai JN, et al. Child-Pugh versus MELD score for predicting the in-hospital mortality of acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding in liver cirrhosis[J]. Int J Clin Exp Med, 2015, 8(1): 751-757. |

| [18] | Fortune BE, Garcia-Tsao G, Ciarleglio M, et al. Child-turcotte-pugh class is best at stratifying risk in variceal hemorrhage: analysis of a US multicenter prospective study[J]. J Clin Gastroenterol, 2017, 51(5): 446-453. DOI:10.1097/MCG.0000000000000733 |

| [19] | Lee SW, Lee TY, Chang CS. Independent factors associated with recurrent bleeding in cirrhotic patients with esophageal variceal hemorrhage[J]. Dig Dis Sci, 2009, 54(5): 1128-1134. DOI:10.1007/s10620-008-0454-0 |

| [20] | Duvnjak M, Barsić N, Tomasić V, et al. Adjusted blood requirement index as indicator of failure to control acute variceal bleeding[J]. Croat Med J, 2006, 47(3): 398-403. |

| [21] | Abraldes JG, Villanueva C, Bañares R, et al. Hepatic venous pressure gradient and prognosis in patients with acute variceal bleeding treated with pharmacologic and endoscopic therapy[J]. J Hepatol, 2008, 48(2): 229-236. DOI:10.1016/j.jhep.2007.10.008 |

| [22] | Chen YC, Chuang CJ, Hsiao KY, et al. Massive transfusion in upper gastrointestinal bleeding: a new scoring system[J]. Ann Med, 2019, 51(3/4): 224-231. DOI:10.1080/07853890.2019.1615122 |

| [23] | Ko BS, Kim YJ, Jung DH, et al. Early risk score for predicting hypotension in normotensive patients with non-variceal upper gastrointestinal bleedin[J]. J Clin Med, 2019, 8(1): 37. DOI:10.3390/jcm8010037 |

| [24] | Chalasani N, Kahi C, Francois F, et al. Improved patient survival after acute variceal bleeding: a multicenter, cohort study[J]. Am J Gastroenterol, 2003, 98(3): 653-659. DOI:10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.07294.x |

| [25] | Villanueva C, Piqueras M, Aracil C, et al. A randomized controlled trial comparing ligation and sclerotherapy as emergency endoscopic treatment added to somatostatin in acute variceal bleeding[J]. J Hepatol, 2006, 45(4): 560-567. DOI:10.1016/j.jhep.2006.05.016 |

2024, Vol. 33

2024, Vol. 33