心脏骤停(cardiac arrest, CA)是全球重要的公共卫生问题之一,《中国心脏骤停与心肺复苏报告(2022年版)》显示我国CA总体发病率为97.1/10万[1]。对于潜在病因可逆、反复CA而不能维持自主心律或使用常规心肺复苏恢复自主循环后难以维持的患者,体外膜肺氧合辅助心肺复苏(extracorporeal cardiopulmonary resuscitation, ECPR)是唯一的救治手段[2]。早期从高级生命支持过渡到静脉-动脉体外膜肺氧合(venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, VA-ECMO)能够改善CA患者的预后[3]。即使在经验丰富的高容量ECMO中心,ECPR患者的结局仍然受到多种混杂因素的影响,而显示出异质性生存结局[4]。目前ECPR的启动决策和预后评估依然存在争议和困难,尽管ECPR给CA患者提供了一段依靠ECMO维持的生存期,但部分患者没有可能痊愈,而引发各种伦理性问题,一定程度上限制了ECPR的开展[5]。

鉴于国内尚缺乏大样本量ECPR启动和终止的时间特征数据,本文回顾性分析南京医科大学第一附属医院急诊中心2015年4月至2023年10月的ECPR患者,总结ECPR启动和终止的时间特征,旨在探讨时间因素与ECPR应用规律及其有效性之间的关系,为ECPR临床实践提供一定的证据支持。

1 资料与方法 1.1 研究对象以2015年4月至2023年10月本中心的207例ECPR患者为研究对象。ECPR启动指征:⑴可逆性病因;⑵年龄 < 80岁;⑶有目击的CA;⑷CA到启动ECPR的时间 < 30 min;⑸基础疾病非终末状态[6]。207例患者均成功启动ECPR治疗,并遵照成人ECPR实践路径系统化管理[7]。最终,排除2例围产期的患者、5例ECMO终止后再启动的患者,共纳入200例ECPR患者进行分析。本研究已获得本院伦理委员会批准(伦审号:2019-NT-12)。

收集ECPR患者的年龄、性别、基础疾病(以查尔森合并症指数评价)、初始心律、无灌流时间(CA至开始胸外按压的时间)、CA-Pump On时间(CA至ECMO开始转流的时间)、ECPR启动前或启动即刻pH和乳酸值、ECMO治疗时间、ECMO终止和90 d存活率等信息。院际联动是指ECMO团队在南京范围内的联动医院启动ECPR流程,为患者进行ECMO置管,再将患者转运至本中心。患者第一个记录在案的节律为心室颤动或无脉性室性心动过速作为初始可电击心律。程序性终止是指患者经过ECPR治疗后好转达到撤离VA-ECMO的标准而终止ECMO治疗[7]。神经功能预后评价采用格拉斯哥-匹兹堡脑功能表现分级(cerebral performance category, CPC)评分,CPC评分1~2级为神经功能预后良好[8]。部分患者放弃治疗或在脱离ECMO后因综合因素死亡,均视为病死率,死亡时间由ECMO开始后计算。

1.2 统计学方法应用SPSS 20.0统计学软件进行数据处理。分类变量表示为计数和百分比,连续变量用平均值±标准差(x±s)或中位数(四分位数)[M(Q1, Q3)]表示。组间比较采用t检验、卡方检验或方差分析,采用Kruskal-Wallis秩和检验对连续变量的排序中位数进行多组比较。以P < 0.05为差异有统计学意义。

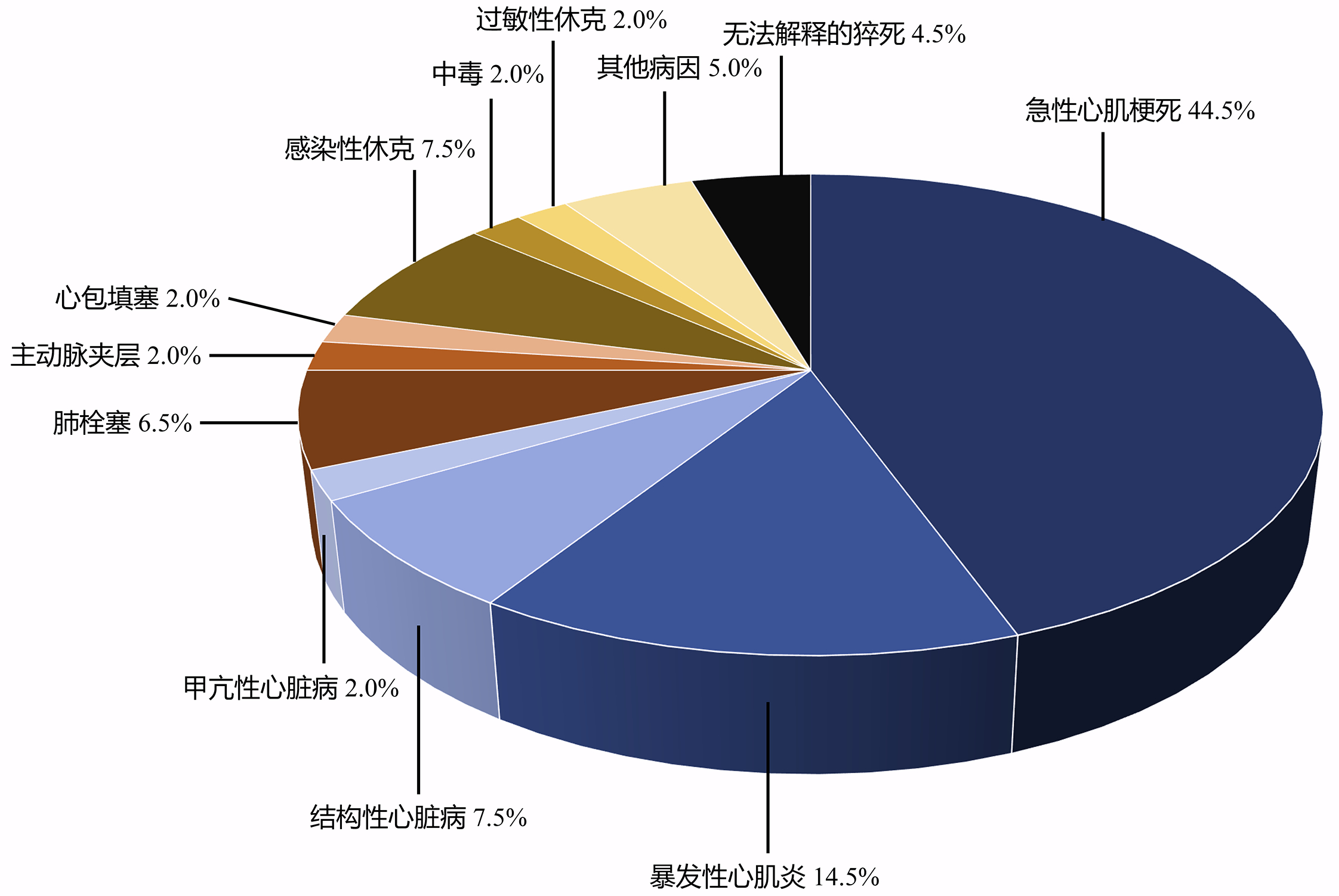

2 结果 2.1 ECPR患者的基本信息200例ECPR患者纳入分析,包括急性心肌梗死89例,暴发性心肌炎29例,结构性心脏病15例,甲亢性心脏病4例,心包填塞4例,肺栓塞13例,主动脉夹层4例,感染性休克15例,过敏性休克4例,中毒4例,其他病因10例,无法解释的猝死9例。见图 1。其中男性141例,女性59例,年龄为(48.6±1.2)岁,查尔森合并症指数为(0.8±0.1),院内心脏骤停(in-hospital cardiac arrest, IHCA)138例(69.0%),院外心脏骤停(out-of-hospital cardiac arrest, OHCA)62例(31.0%)。有院际联动59例(29.5%),初始可电击心律100例(50.0%),ECPR初始血气pH值7.18 (6.94, 7.33)、乳酸值(12.27±0.46) mmol/L,无灌流时间1(1, 3)min,CA-Pump On时间75(47, 130)min,ECMO治疗时间4(2, 7)d。ECPR日间时段启动113例(56.5%),日间时段终止151例(75.5%)。ECMO程序性终止84例(42.0%),90 d存活68例(34.0%),其中61例(89.7%)神经功能预后良好。90 d死亡共132例,死亡时间3(1, 7)d,其中ECMO程序性终止后因综合因素死亡16例,ECMO非程序性终止死亡116例。见表 1。

|

| 图 1 ECPR患者的原发病分布图(n=200) Fig 1 Distrubtion map of primary diseases in ECPR patients(n=200) |

|

|

| 基本信息 | 数值 |

| 年龄(岁) a | 48.6±1.2 |

| 性别(男/女,n) | 141/59 |

| 查尔森合并症指数a | 0.8±0.1 |

| IHCA/OHCA(n) | 138/62 |

| 院际联动(n, %) | 59 (29.5) |

| 初始可电击心律(n, %) | 100 (50.0) |

| pH值b | 7.18 (6.94, 7.33) |

| 乳酸值(mmol/L) a | 12.27±0.46 |

| 无灌流时间(min) b | 1 (1, 3) |

| CA-Pump On时间(min) b | 75 (47, 130) |

| 日间/夜晚时段启动(n) | 113/87 |

| 日间/夜晚时段终止(n) | 151/49 |

| ECMO程序性/非程序性终止(n) | 84 /116 |

| ECMO治疗时间(d) b | 4 (2, 7) |

| 90 d存活(n, %) | 68 (34.0) |

| CPC 1~2级(n) | 61 |

| 90 d死亡(n, %) | 132 (66.0) |

| 死亡时间(d)b | 3 (1, 7) |

| 注:a为(x±s),b为M(Q1, Q3) | |

200例ECPR患者中,90 d存活68例,死亡132例。90 d存活与死亡组之间,年龄、性别、基础疾病、院际联动、CA-Pump On时间、启动时段均差异无统计学意义。与90 d死亡组比较,存活组中85.3%为IHCA,初始可电击心律的比例高(66.2% vs. 41.7%),ECPR初始血气pH值高[7.33 (7.15, 7.41) vs. 7.10 (6.89, 7.27)]、乳酸值低[(8.76±0.80) mmol/L vs. (14.05±0.48) mmol/L],无灌流时间短[1 (1, 1) min vs. 1 (1, 5) min],ECMO治疗时间长[6 (5, 8) d vs. 3 (1, 6) d],均为程序性终止ECMO,且终止时间绝大多数(94.1%)在日间时段,差异有统计学意义(P < 0.05)。见表 2。

| 指标 | 90 d存活组(n=68) | 90 d死亡组(n=132) | 统计值 | P值 |

| 年龄(岁)a | 48.9±2.0 | 48.4±1.5 | 0.21 | 0.83 |

| 性别(男/女,n) | 42/26 | 99/33 | 3.78 | 0.05 |

| 查尔森合并症指数a | 0.8±0.1 | 0.8±0.1 | 0.61 | 0.54 |

| IHCA/OHCA (n) | 58/10 | 80/52 | 12.79 | < 0.001 |

| 院际联动(n, %) | 21 (30.9%) | 38 (28.8%) | 0.09 | 0.76 |

| 初始可电击心律(n, %) | 45 (66.2%) | 55 (41.7%) | 10.78 | < 0.001 |

| pH值b | 7.33 (7.15, 7.41) | 7.10 (6.89, 7.27) | 5.34 | < 0.001 |

| 乳酸值(mmol/L)a | 8.76±0.80 | 14.05±0.48 | 5.95 | < 0.001 |

| 无灌流时间(min) b | 1 (1, 1) | 1 (1, 5) | 3.88 | < 0.001 |

| CA-Pump On时间(min) b | 60 (45, 127) | 81 (50, 137) | 0.80 | 0.42 |

| 日间/夜晚时段启动(n) | 35/33 | 78/54 | 1.06 | 0.30 |

| 日间/夜晚时段终止(n) | 64/4 | 87/45 | 19.31 | < 0.001 |

| ECMO程序性/非程序性终止(n) | 68/0 | 16/116 | 142.3 | < 0.001 |

| ECMO治疗时间(d) b | 6 (5, 8) | 3 (1, 6) | 2.64 | 0.01 |

| 注:a为(x±s),b为M(Q1, Q3) | ||||

200例ECPR患者中,IHCA组138例,OHCA组62例。IHCA和OHCA组之间,年龄、基础疾病、院际联动、初始可电击心律、CA-Pump On时间、启动和终止时段、ECMO治疗时间和死亡时间均差异无统计学意义。与IHCA组比较,OHCA组的男性比例高(80.6% vs. 65.9%),无灌流时间长[5 (3, 12) min vs. 1 (1, 1) min],ECPR初始血气pH值低[7.00 (6.87, 7.27) vs. 7.23 (7.02, 7.36)]、乳酸值高[(14.09±0.66) mmol/L vs. (11.42±0.58)mmol/L],90 d存活率低(16.1% vs. 42.0%),且大多数(77.4%)为非程序性终止ECMO,差异有统计学意义(P < 0.05)。见表 3。

| 指标 | IHCA组(n=138) | OHCA (n=62) | 统计值 | P值 |

| 年龄(岁)a | 49.2±1.4 | 47.3±2.1 | 0.75 | 0.45 |

| 性别(男/女,n) | 91/47 | 50/12 | 4.45 | 0.04 |

| 查尔森合并症指数a | 0.9±0.1 | 0.7±0.1 | 0.96 | 0.34 |

| 院际联动(n, %) | 35 (25.4%) | 24 (38.7%) | 3.67 | 0.06 |

| 初始可电击心律(n, %) | 71 (51.4%) | 29 (46.8%) | 0.37 | 0.54 |

| pH值b | 7.23 (7.02, 7.36) | 7.00 (6.87, 7.27) | 3.97 | < 0.001 |

| 乳酸值(mmol/L)a | 11.42±0.58 | 14.09±0.66 | 2.77 | 0.01 |

| 无灌流时间(min) b | 1 (1, 1) | 5 (3, 12) | 11.64 | < 0.001 |

| CA-Pump On时间(min) b | 60 (40, 123) | 92 (70, 145) | 1.77 | 0.08 |

| 日间/夜晚时段启动(n) | 78/60 | 35/27 | 0.00 | 0.99 |

| 日间/夜晚时段终止(n) | 109/29 | 42/20 | 2.92 | 0.09 |

| ECMO程序性/非程序性终止(n) | 70/68 | 14/48 | 13.91 | < 0.001 |

| ECMO治疗时间(d) b | 5 (2, 7) | 3 (1, 6) | 1.49 | 0.14 |

| 死亡时间(d) b | 3 (1, 8) | 3 (1, 6) | 1.36 | 0.18 |

| 90 d存活(n, %) | 58 (42.0%) | 10 (16.1%) | 12.79 | < 0.001 |

| 注:a为(x±s),b为M(Q1, Q3) | ||||

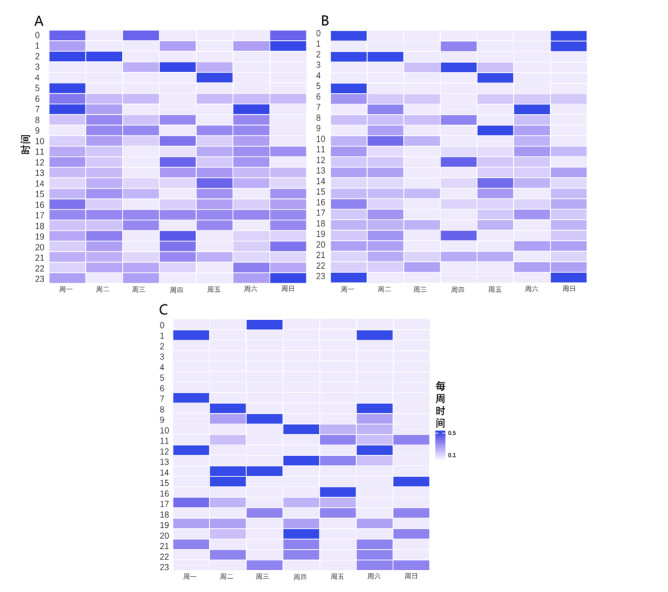

200例ECPR患者中,各时间段均有ECPR启动,IHCA-ECPR随机启动,OHCA-ECPR仅有3例(4.8%)在凌晨时段(00:00~06:00)启动。日间时段(08:00~17:00)启动113例(56.5%),夜晚时段(18:00~次日07:00)启动87例(43.5%)。见图 2。日间与夜晚时段启动组之间年龄、性别、基础疾病、IHCA/OHCA、院际联动、初始可电击心律、ECPR初始血气pH值和乳酸值、无灌流时间、ECMO治疗时间、死亡时间、程序性终止和90 d存活率均差异无统计学意义。与日间时段启动组比较,夜晚时段启动组的CA-Pump On时间长[90(51, 150) min vs. 67(45, 117)min],日间时段终止的比例高(83.9% vs. 69.0%),差异有统计学意义(P < 0.05)。见表 4。

|

| 图 2 ECPR启动时间分布图(A:总体; B:IHCA; C:OHCA) Fig 2 Distrubtion map of ECPR initiation time(A: Total; B: IHCA; C: OHCA) |

|

|

| 指标 | 日间时段启动组(n=113) | 夜晚时段启动组(n=87) | 统计值 | P值 |

| 年龄(岁) a | 50.0±1.6 | 46.8±1.8 | 1.35 | 0.18 |

| 性别(男/女, n) | 83/30 | 58/29 | 1.09 | 0.30 |

| 查尔森合并症指数a | 0.9±0.1 | 0.7±0.1 | 1.61 | 0.11 |

| IHCA/OHCA (n) | 78/35 | 60/27 | 0.00 | 0.99 |

| 院际联动(n, %) | 31 (27.4) | 28 (32.2) | 0.53 | 0.47 |

| 初始可电击心律(n, %) | 62 (54.9) | 38 (43.7) | 2.46 | 0.12 |

| pH值b | 7.17 (6.91, 7.36) | 7.19 (6.96, 7.32) | 0.70 | 0.49 |

| 乳酸值mmol/L a | 12.2±0.6 | 12.4±0.7 | 0.26 | 0.79 |

| 无灌流时间(min)b | 1 (1, 3) | 1 (1, 3) | 0.90 | 0.37 |

| CA-Pump On时间(min)b | 67 (45, 117) | 90 (51, 150) | 2.24 | 0.03 |

| 日间/夜晚时段终止(n) | 78/35 | 73/14 | 5.89 | 0.02 |

| ECMO程序性/非程序性终止(n) | 47/66 | 37/50 | 0.02 | 0.89 |

| ECMO治疗时间(d)b | 4 (2, 7) | 4 (1, 7) | 0.55 | 0.59 |

| 死亡时间(d)b | 3 (1, 7) | 2 (1, 6) | 0.54 | 0.59 |

| 90 d存活(n, %) | 35 (31.0) | 33 (37.9) | 1.06 | 0.30 |

| 注:a为(x±s),b为M(Q1, Q3) | ||||

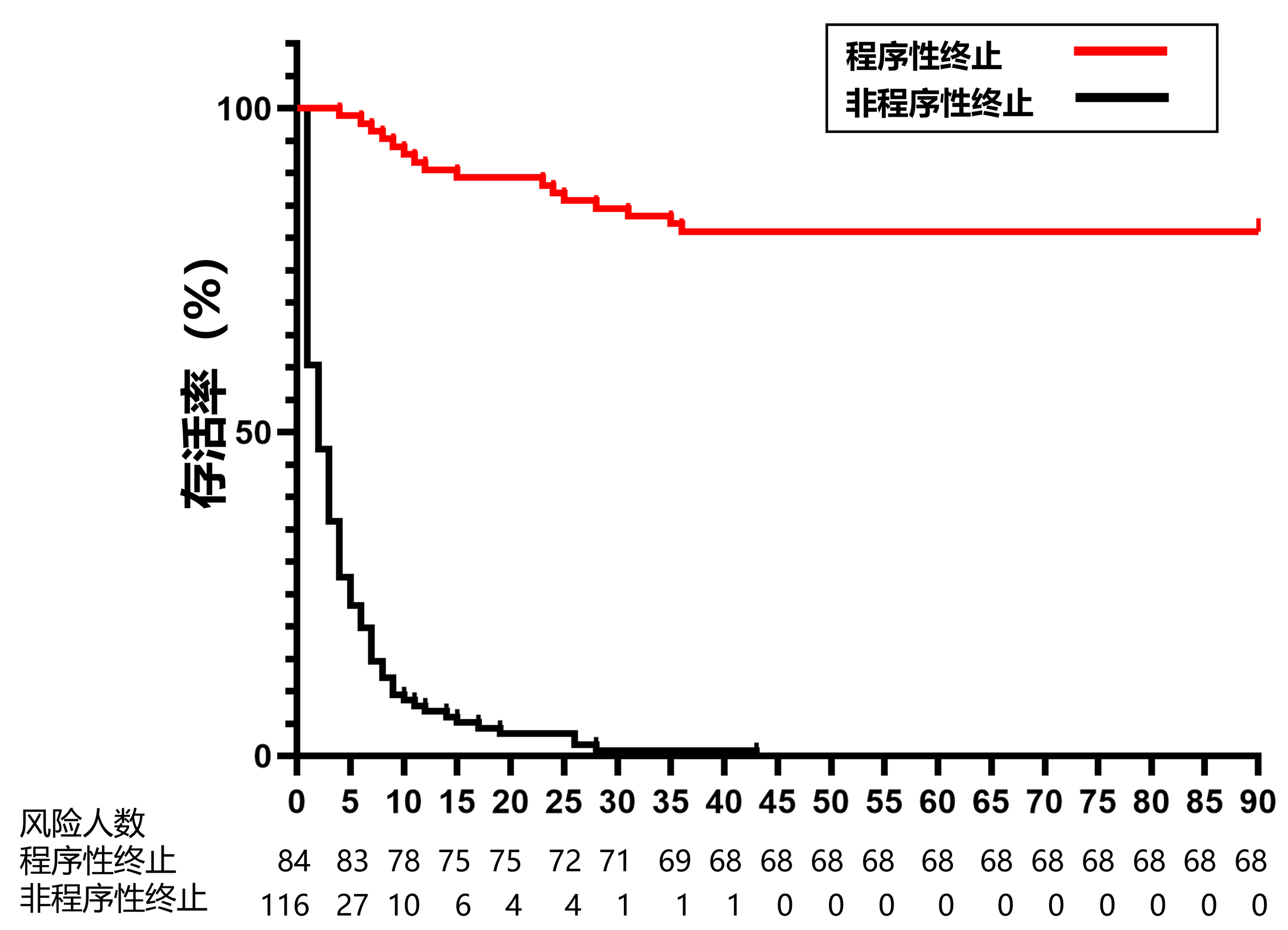

200例ECPR患者中,程序性终止84例,非程序性终止116例。有75.5%(n=151)的患者在日间时段终止ECMO,其中程序性终止78例,非程序性终止73例。中位ECMO治疗时间为4(2, 7)d,仅有4.5%(n=9)的ECPR患者ECMO治疗时间超过2周,其中2例程序性终止ECMO且90 d存活,7例非程序终止而死亡。有23.0%的ECPR患者在1 d内死亡,56.8%的死亡病例发生在ECPR后的3 d内。程序性终止组与非程序性终止组之间年龄、性别、基础疾病、CA-Pump On时间、启动时段均差异无统计学意义。与非程序性终止组比较,程序性终止组中83.3%为IHCA,初始可电击心律的比例高(66.7% vs. 37.9%),ECPR初始血气pH值高[7.31(7.09, 7.41)vs. 7.05(6.88, 7.26)]、乳酸值低[(8.99±0.71) mmol/L vs.(14.67±0.48)mmol/L]、无灌流时间短[1(1, 2) min vs. 1(1, 5)min],ECMO治疗时间长[6(5, 8) d vs. 2(1, 5)d],90d存活率达81.0%。程序性终止组有16例(19.0%)终止ECMO后因综合因素死亡,死亡时间较非程序性终止组长[13(8, 27) d vs. 2(1, 5)d],差异有统计学意义(P < 0.05)。见图 3、表 5。

|

| 图 3 程序性终止组与非程序性终止组的Kaplan-Meier生存曲线图 Fig 3 Kaplan-Meier survival curve for the procedural termination group and non-procedural termination group |

|

|

| 指标 | 程序性终止组(n=84) | 非程序性终止组(n=116) | 统计值 | P值 |

| 年龄(岁) a | 48.9±1.8 | 48.4±1.6 | 0.19 | 0.85 |

| 性别(男/女,n) | 54/30 | 87/29 | 2.69 | 0.10 |

| 查尔森合并症指数a | 0.9±0.1 | 0.8±0.1 | 0.49 | 0.63 |

| IHCA/OHCA (n) | 70/14 | 68/48 | 13.91 | < 0.001 |

| 院际联动(n, %) | 22 (26.2%) | 37 (31.9%) | 0.76 | 0.38 |

| 初始可电击心律(n, %) | 56 (66.7%) | 44 (37.9%) | 16.09 | < 0.001 |

| pH值b | 7.31 (7.09, 7.41) | 7.05 (6.88, 7.26) | 5.78 | < 0.001 |

| 乳酸值a | 8.99±0.71 | 14.67±0.48 | 6.86 | < 0.001 |

| 无灌流时间(min)b | 1 (1, 2) | 1 (1, 5) | 3.97 | < 0.001 |

| CA-Pump On时间(min) b | 60 45, 120) | 83 (50, 141) | 1.38 | 0.17 |

| 日间/夜晚时段启动(n) | 48/36 | 65/51 | 0.02 | 0.88 |

| 日间/夜晚时段终止(n) | 78/6 | 73/43 | 23.59 | < 0.001 |

| ECMO治疗时间(d) b | 6 (5, 8) | 2 (1, 5) | 2.78 | 0.01 |

| 死亡时间(d) | 13(8, 27) | 2 (1, 5) | 7.17 | < 0.001 |

| 90 d存活(n, %) | 68 (81.0%) | 0 (0%) | 142.3 | < 0.001 |

| 注:a为(x±s),b为M(Q1, Q3) | ||||

随着体外生命支持技术的发展和心脏骤停中心的建设,ECPR已成为难治性CA患者的常用治疗策略,体外生命支持组织(extracorporeal life support organization, ELSO)登记超过1.3万例的成年ECPR患者中,出院存活率为30%[9]。尽管ECPR改善CA患者的生存率和神经系统结局,但ECPR的结果是异质的,并受到高获益患者选择的影响,在实际开展过程中仍有很多的问题和挑战。

ECPR作为限制性技术,在美国所有IHCA中的使用率 < 1%,启动决策受到患者年龄、性别、种族、基础疾病、医院条件等多因素的影响,更年轻、更健康的男性患者接受ECPR的概率明显更高[10]。ECPR不推荐常规用于所有CA患者,尚缺乏统一的启动标准,应谨慎选择ECPR可能获益的患者[11]。本研究200例ECPR患者中,心源性病因占68.5%,男性多于女性,IHCA、初始可电击心律、无灌流时间短的CA患者实施ECPR有更大的益处,符合CA的流行病学分布和国内外ECPR领域的主流研究结果[12-13]。短暂的无灌流时间和初始可电击心律是ECPR患者预后良好的可靠指标,流畅的ECPR生命救治链是存活的关键[14]。ECPR初始血气结果亦与不良预后直接相关,pH反映CA后组织缺血缺氧的程度和持续时间,血乳酸含量反映末梢组织血液灌注的程度,联合pH值和血乳酸有助于预测ECPR患者的生存[15]。尽管ELSO推荐pH值< 7联合血乳酸 > 7 mmol/L预测VA-ECMO患者1年生存率 < 7%的“三七法则”[16],但特异度有待进一步提高,不能达到预测ECPR患者结局的要求。仍需要大型随机对照试验来更好地确定ECPR可能提供益处的患者。

环境温度是CA的影响因素之一,在极端天气较多的冬夏季节,猝死发生率高于气温较为稳定的春秋季节[17]。OHCA亦存在明显的昼夜节律,早晚时段的发病率最高,凌晨时段发病率最低[18]。《中国心脏骤停与心肺复苏报告》发现经紧急医疗服务救治的OHCA患者中,1~3月和10~12月的发病例数高于4~9月的发病例数,24 h内发病高峰在上午6至9时及下午18时[1]。IHCA发生率的是否存在季节和昼夜节律的变化,目前尚不明确[19-20]。本研究200例ECPR患者中,4~9月IHCA-ECPR启动82例,OHCA-ECPR启动33例,季节因素对ECPR的启动未产生明显影响,可能与南京地区属于亚热带季风气候,年平均温度15℃,极端天气较少的气候特点有关。在美国,ECPR的启动受到昼夜因素的明显影响,ECPR的使用频率在白天明显更高[10]。本中心各时间段均有ECPR启动,OHCA-ECPR仅有3例(4.8%)在凌晨时段(00:00~06:00)启动,符合OHCA的昼夜节律[18],而IHCA-ECPR随机启动。尽管昼夜启动时间因素对ECPR结局无明显影响,但ECPR夜晚时段启动组的CA-Pump On时间仍有所延长,应加强7×24 h全天候ECPR团队的建设[21]。

有研究报道ECPR后24 h内的病死率高达57.0%,在ECPR启动后的处理中,大部分死亡事件发生在早期[22]。病情的严重程度如酸中毒、高乳酸血症、非可电击心律与非程序性终止ECMO的决定密切相关,主要是因为感知到不良的预后而停止生命维持治疗[23]。如果CA病因无法纠正或ECMO治疗无效,则应考虑早期终止ECPR,然而基于假定的不良神经功能预后,可能会导致不恰当甚至错误终止ECPR的事件出现,需加强对ECPR患者神经功能的监测与评估[24]。在本研究中,半数以上的死亡病例发生在ECPR启动后的3 d内,通常在接受ECPR治疗ICU入院后的次日[ECMO治疗时间2 (1, 5) d]作出非程序性终止ECMO的决定,与ELSO的统计数据一致[23, 25]。非程序性终止ECMO的患者悉数死亡,而程序性终止ECMO的患者中有19.0%的患者因综合因素死亡,与Carlson等[26]和Makhoul等[27]的研究结果相仿。值得注意的是,有77.4%的OHCA-ECPR是非程序性终止的,与OHCA-ECPR较低的存活率有关。尽管ECPR的启动时间无规律可循,但大多数ECPR患者在日间时段终止ECMO。在日间非程序性终止ECMO可能和国内的丧葬风俗习惯有关,而在日间工作时段程序性终止ECMO,则可预留充足的时间处理可能在ECMO撤离后发生的急性并发症。

本文首次报道国内ECPR启动和终止的时间特征数据,结果显示,对IHCA、初始可电击心律和无灌流时间短的患者实施ECPR具有潜在高获益。ECPR的启动时间无规律且对结局无影响,死亡事件易发生在ECPR启动后的早期,ECPR的终止时间多集中在日间工作时段,专职的7×24小时全天候ECPR团队和高效的ECPR生命救治链将会使更多的CA患者从ECPR中获益。

利益冲突 所有作者声明无利益冲突

作者贡献声明 张华忠、张忠满:研究设计、数据收集;胡德亮、孙峰、李伟、张刚:数据整理、统计学分析;梅勇、陈旭锋:体外膜肺氧合专业指导、基金支持;张华忠、吕金如:论文撰写、论文修改

| [1] | 中国医疗保健国际交流促进会胸痛分会. 院外心脏骤停发病率[M]. //中国心脏骤停与心肺复苏报告(2022年版). 北京: 人民卫生出版社, 2023: 4. |

| [2] | Panchal AR, Berg KM, Hirsch KG, et al. 2019 American heart association focused update on advanced cardiovascular life support: use of advanced airways, vasopressors, and extracorporeal cardiopulmonary resuscitation during cardiac arrest: an update to the American heart association guidelines for cardiopulmonary resuscitation and emergency cardiovascular care[J]. Circulation, 2019, 140(24): e881-e894. DOI:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000732 |

| [3] | Lunz D, Calabrò L, Belliato M, et al. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for refractory cardiac arrest: a retrospective multicenter study[J]. Intensive Care Med, 2020, 46(5): 973-982. DOI:10.1007/s00134-020-05926-6 |

| [4] | Karve S, Lahood D, Diehl A, et al. The impact of selection criteria and study design on reported survival outcomes in extracorporeal oxygenation cardiopulmonary resuscitation (ECPR): a systematic review and meta-analysis[J]. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med, 2021, 29(1): 142. DOI:10.1186/s13049-021-00956-5 |

| [5] | Suverein MM, Shaw D, Lorusso R, et al. Ethics of ECPR research[J]. Resuscitation, 2021, 169: 136-142. DOI:10.1016/j.resuscitation.2021.08.007 |

| [6] | Michels G, Wengenmayer T, Hagl C, et al. Recommendations for extracorporeal cardiopulmonary resuscitation (eCPR): consensus statement of DGⅡN, DGK, DGTHG, DGfK, DGNI, DGAI, DIVI and GRC[J]. Clin Res Cardiol, 2019, 108(5): 455-464. DOI:10.1007/s00392-018-1366-4 |

| [7] | 中国老年医学学会急诊医学分会, 中国老年医学学会急诊医学分会ECMO工作委员会. 成人体外膜肺氧合辅助心肺复苏(ECPR)实践路径[J]. 中华急诊医学杂志, 2019, 28(10): 1197-1203. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.issn.1671-0282.2019.10.005 |

| [8] | Sandroni C, Cariou A, Cavallaro F, et al. Prognostication in comatose survivors of cardiac arrest: an advisory statement from the European Resuscitation Council and the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine[J]. Resuscitation, 2014, 85(12): 1779-1789. DOI:10.1016/j.resuscitation.2014.08.011 |

| [9] | Wengenmayer T, Tigges E, Staudacher DL. Extracorporeal cardiopulmonary resuscitation in 2023[J]. Intensive Care Med Exp, 2023, 11(1): 74. DOI:10.1186/s40635-023-00558-8 |

| [10] | Tonna JE, Selzman CH, Girotra S, et al. Patient and institutional characteristics influence the decision to use extracorporeal cardiopulmonary resuscitation for In-hospital cardiac arrest[J]. J Am Heart Assoc, 2020, 9(9): e015522. DOI:10.1161/JAHA.119.015522 |

| [11] | Kratzert WB, Gudzenko V. ECPR or do not ECPR-who and how to choose[J]. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth, 2020, 34(5): 1195-1197. DOI:10.1053/j.jvca.2020.01.037 |

| [12] | Empana JP, Lerner I, Valentin E, et al. Incidence of sudden cardiac death in the European union[J]. J Am Coll Cardiol, 2022, 79(18): 1818-1827. DOI:10.1016/j.jacc.2022.02.041 |

| [13] | Bertic M, Worme M, Foroutan F, et al. Predictors of survival and favorable neurologic outcome in patients treated with eCPR: a systematic review and meta-analysis[J]. J Cardiovasc Transl Res, 2022, 15(2): 279-290. DOI:10.1007/s12265-021-10195-9 |

| [14] | Richardson ASC, Tonna JE, Nanjayya V, et al. Extracorporeal cardiopulmonary resuscitation in adults. interim guideline consensus statement from the extracorporeal life support organization[J]. ASAIO J, 2021, 67(3): 221-228. DOI:10.1097/mat.0000000000001344 |

| [15] | 孙峰, 张华忠, 梅勇, 等. 早期乳酸判断体外心肺复苏患者预后的研究[J]. 中华急诊医学杂志, 2022, 31(12): 1608-1611. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.issn.1671-0282.2022.12.006 |

| [16] | Dib N, Belaroussi Y, Mansour A, et al. Association of arterial blood pH at cannulation with 1 year survival among veno-arterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation recipients: the three seven rule[J]. ASAIO J, 2023, 69(7): e287-e292. DOI:10.1097/MAT.0000000000001964 |

| [17] | Kranc H, Novack V, Shtein A, et al. Extreme temperature and out-of-hospital-cardiac-arrest. Nationwide study in a hot climate country[J]. Environ Health, 2021, 20(1): 38. DOI:10.1186/s12940-021-00722-1 |

| [18] | Ramireddy A, Chugh SS. Do peak times exist for sudden cardiac arrest?[J]. Trends Cardiovasc Med, 2021, 31(3): 172-176. DOI:10.1016/j.tcm.2020.01.008 |

| [19] | Ashraf M, Sulaiman S, Alyami B, et al. Seasonal variation in the incidence of In-hospital cardiac arrest[J]. JACC Clin Electrophysiol, 2023, 9(8 Pt 3): 1755-1767. DOI:10.1016/j.jacep.2023.04.012 |

| [20] | McGuigan PJ, Edwards J, Blackwood B, et al. The association between time of in hospital cardiac arrest and mortality; a retrospective analysis of two UK databases[J]. Resuscitation, 2023, 186: 109750. DOI:10.1016/j.resuscitation.2023.109750 |

| [21] | 马莉, 李明雪, 马雪倩, 等. 急诊科体外心肺复苏术快速反应医护团队的建立和实施效果[J]. 中华急诊医学杂志, 2023, 32(11): 1564-1568. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.issn.1671-0282.2023.11.028 |

| [22] | Han KS, Kim SJ, Lee EJ, et al. Experience of extracorporeal cardiopulmonary resuscitation in a refractory cardiac arrest patient at the emergency department[J]. Clin Cardiol, 2019, 42(4): 459-466. DOI:10.1002/clc.23169 |

| [23] | Carlson JM, Etchill E, Whitman G, et al. Early withdrawal of life sustaining therapy in extracorporeal cardiopulmonary resuscitation (ECPR): results from the Extracorporeal Life Support Organization registry[J]. Resuscitation, 2022, 179: 71-77. DOI:10.1016/j.resuscitation.2022.07.038 |

| [24] | Brain injury brain injury and neurologic outcome in patients undergoing extracorporeal cardiopulmonary resuscitation: a systematic review and meta-analysis: erratum[J]. Crit Care Med, 2020, 48(9): e845. DOI: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000004557. |

| [25] | Naito H, Sakuraya M, Hongo T, et al. Prevalence, reasons, and timing of decisions to withhold/withdraw life-sustaining therapy for out-of-hospital cardiac arrest patients with extracorporeal cardiopulmonary resuscitation[J]. Crit Care, 2023, 27(1): 252. DOI:10.1186/s13054-023-04534-2 |

| [26] | Carlson JM, Etchill EW, Enriquez CAG, et al. Population characteristics and markers for withdrawal of life-sustaining therapy in patients on extracorporeal membrane oxygenation[J]. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth, 2022, 36(3): 833-839. DOI:10.1053/j.jvca.2021.04.040 |

| [27] | Makhoul M, Heuts S, Mansouri A, et al. Understanding the "extracorporeal membrane oxygenation gap" in veno-arterial configuration for adult patients: timing and causes of death[J]. Artif Organs, 2021, 45(10): 1155-1167. DOI:10.1111/aor.14006 |

2024, Vol. 33

2024, Vol. 33