社区获得性肺炎(community acquired pneumonia,CAP)在成人中是一个日益严重的问题,发病率及病死率随着年龄增加而逐渐升高[1]。在65岁以上患者中CAP的年发病率为每1000名居民每年8至48例,在85岁以上的患者中甚至更高[2-3]。65岁及以上患者的住院率(每年每10万人中约有2 000人)比年轻人群高10倍[4]。脓毒症被定义为因宿主对感染的反应失调而导致的危及生命的器官功能障碍[5]。脓毒症相关的死亡病例约占全球死亡病例的20%以及新生儿死亡病例的15%[6],老年脓毒症患者发病率及病死率更高[7]。脓毒症在CAP患者中具有较高发生率,可引起免疫功能紊乱、凝血功能紊乱、微循环障碍、代谢紊乱、多器官功能衰竭等导致患者出现不良预后[8]。对高死亡风险的老年CAP相关脓毒症患者可以通过有创机械通气等高级生命支持手段来降低[9-10]。因此,对高病死率风险的老年CAP相关脓毒症患者的早期治疗尤为重要。本研究探讨老年CAP相关脓毒症患者的预后预测因素并构建预后预测模型,以便早期评估患者死亡相对风险,为临床医生制定个性化干预措施提供指导。

1 资料与方法 1.1 研究对象回顾性选取2020年10月至2022年10月就诊于宁夏医科大学总医院的老年CAP相关脓毒症的患者。纳入标准:依据中国成人CAP诊断和治疗指南(2016年版)[1]诊断为CAP;依据Sepsis 3.0[5]诊断为脓毒症;年龄≥65岁;临床资料完整者。排除标准:年龄<65岁;合并其他感染者;合并其他原因可能导致的脓毒症者;合并慢性肾病、慢性肝病、实体恶性肿瘤、血液系统及急性心脑血管疾病的患者;随访时间不足30 d或临床病例资料不全者。本研究经医院伦理委员会批准通过(KYLL-2023-0370)。

1.2 临床资料收集人口学特征包括年龄和性别;基础疾病包括高血压、糖尿病及冠心病病史;入院时的体温、心率、呼吸频率、收缩压、收缩压、平均动脉压及指脉氧;入院后24 h内即刻测定白细胞计数、中性粒细胞绝对值、淋巴细胞绝对值、单核细胞绝对值、血小板计数、降钙素原、乳酸、D-二聚体定量、氨基末端B型脑钠肽前体、凝血酶原活动度、凝血酶原国际标准比值、纤维蛋白原定量、活化部分凝血酶原时间、凝血酶原时间、总胆红素、肌酐、尿素等;评分系统包括肺炎严重指数(pneumonia severity index,PSI)评分、CURB-65评分及脓毒症相关序贯器官衰竭(sequential organ failure assessment,SOFA)评分。患者治疗均依据中国成人CAP诊断和治疗指南(2016年版)及国际严重脓毒症和脓毒性休克指南。观察结局指标为入院30d生存情况。

1.3 统计学方法统计分析采用SPSS 27.0和R 4.2.2软件。计量资料采用均数±标准差(x±s)或中位数(四分位数间距)表示,使用t检验或非参数Mann-Whitney U检验在组间进行比较。计数资料用频数(%)表示,组间比较采用χ2或Fisher精确检验。LASSO回归模型适用于临床资料特征的缩减,以获取老年CAP相关脓毒症患者预后的危险因素(非零系数),多因素Logistic回归方法适用于独立危险因素的进一步筛选。回归分析所筛选的因素用R软件构建列线图预测模型,并对构建的模型通过受试者工作特征曲线、决策曲线分析和calibrate校准曲线进行验证。以P < 0.05为差异有统计学意义。

2 结果 2.1 研究对象的临床资料本研究共纳入472例老年CAP相关脓毒症患者,包括建模人群(331例)和验证人群(141例),两组人群在临床资料比较,差异均无统计学意义(P > 0.05,表 1)。

| 指标 | 建模人群(n=331) | 验证人群(n=141) | t/Z/χ2 | P值 |

| 年龄(岁)a | 77(72, 82) | 76(71, 81) | -0.981 | 0.327 |

| 男性b | 203(61.3) | 94(66.7) | 1.207 | 0.272 |

| 高血压b | 193(58.3) | 82(58.2) | 0.001 | 0.976 |

| 糖尿病b | 97(29.3) | 35(24.9) | 0.986 | 0.321 |

| 冠心病b | 94(28.4) | 46(32.6) | 0.846 | 0.358 |

| 体温(℃)a | 36.6(36.3, 36.8) | 36.6(36.3, 36.8) | -0.693 | 0.488 |

| 呼吸(次/min)a | 20(18, 20) | 20(18, 21) | -0.466 | 0.641 |

| 心率(次/min)a | 91(81, 106) | 94(79, 111) | -1.097 | 0.273 |

| 收缩压(mmHg)a | 137(121, 152) | 134(118, 149) | -0.824 | 0.410 |

| 舒张压(mmHg)c | 76.9±12.8 | 76.9±11.8 | -0.03 | 0.998 |

| 平均动脉压(mmHg)c | 96.7±14.6 | 96.7±12.4 | 0.01 | 0.992 |

| 血氧饱和度(%)a | 88(81, 92) | 86(78, 93) | -1.302 | 0.193 |

| WBC(×109/L)a | 7.00(5.11, 9.61) | 7.11(5.36, 10.71) | -1.448 | 0.148 |

| NEUT#(×109/L)a | 5.54(3.77, 7.81) | 5.64(4.32, 8.85) | -1.754 | 0.079 |

| LYM#(×109/L)a | 0.77(0.48, 1.11) | 0.74(0.50, 1.19) | -0.757 | 0.449 |

| MXD#(×109/L)a | 0.51(0.32, 0.72) | 0.45(0.31, 0.63) | -1.637 | 0.102 |

| PLT(×109/L)a | 177(134, 235) | 173(143, 234) | -0.366 | 0.715 |

| PCT(ng/mL)a | 0.10(0.07, 0.17) | 0.09(0.07, 0.19) | -0.268 | 0.789 |

| LAC(mmol/L)a | 1.97(1.60, 2.51) | 1.96(1.60, 2.61) | -0.685 | 0.494 |

| D-D(ug/mL)a | 0.95(0.58, 1.65) | 1.19(0.72, 1.99) | -1.893 | 0.058 |

| NT-proBNP(pg/mL)a | 527(300, 1120) | 676(330, 1480) | -1.728 | 0.084 |

| PTA(%)a | 86(72, 97) | 84(73, 93) | -1.267 | 0.205 |

| INRa | 1.06(0.98, 1.14) | 1.08(1.01, 1.16) | -1.187 | 0.235 |

| FIB(g/L)a | 4.43(3.84, 5.19) | 4.38(3.66, 5.21) | -0.503 | 0.615 |

| APTT(s)a | 29.5(27.4, 32.5) | 30.2(27.6, 33.4) | -1.505 | 0.132 |

| PT(s)a | 11.8(10.9, 12.7) | 11.8(11.0, 12.8) | -0.511 | 0.610 |

| TBIL(μmom/L)a | 15.2(11.7, 22.0) | 16.6(11.5, 22.5) | -0.613 | 0.540 |

| UREA(mmol/L)a | 6.57(5.30, 8.83) | 6.79(5.10, 9.41) | -0.408 | 0.683 |

| CREA(μmom/L)a | 70.0(55.4, 88.5) | 65.8(56.8, 83.4) | -0.878 | 0.380 |

| PSI评分a | 85(74, 100) | 84(75, 100) | -0.518 | 0.605 |

| CURB-65评分a | 2(1, 2) | 2(1, 2) | -0.065 | 0.948 |

| SOFA评分a | 3(2, 4) | 3(2, 4) | -1.371 | 0.170 |

| 注:WBC为白细胞计数,NEUT#为中性粒细胞绝对值,LYM#为淋巴细胞绝对值,MXD#为单核细胞绝对值,PLT为血小板计数,PCT为降钙素原,LAC为乳酸,D-D为D-二聚体定量,NT-proBNP为氨基末端B型脑钠肽前体,PTA为凝血酶原活动度,INR为凝血酶原国际标准比值,FIB为纤维蛋白原定量,APTT为活化部分凝血酶原时间,PT为凝血酶原时间,TBIL为总胆红素,CREA为肌酐,UREA为尿素,PSI为肺炎严重指数评分,CURB-65评分为一种常用肺炎评分,SOFA为序贯器官衰竭评分,a为M(Q1,Q3),b为n(%), c为x±s | ||||

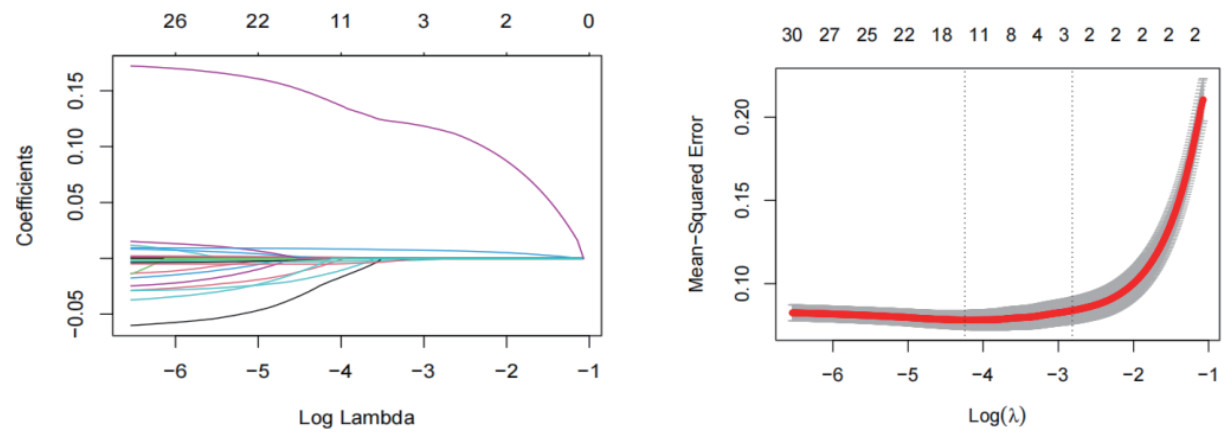

建模人群根据入院30 d生存情况分为生存组232例和死亡组99例,通过LASSO回归分析共获得3个危险因素(非零系数),分别为血氧饱和度、PSI及SOFA评分(图 1)。应用多因素Logistic回归方法分析上述危险因素,结果显示PSI及SOFA评分为老年CAP相关脓毒症患者预后的独立危险因素(表 2)。

|

| 图 1 建模人群的LASSO回归模型危险因素筛选 Fig 1 Screening for risk factors in the modeling group using the LASSO binary logistic regression model. |

|

|

| 指标 | B | SE | Wald | OR | 95%CI | P值 |

| 血氧饱和度 | -0.049 | 0.028 | 3.020 | 0.952 | 0.901~1.006 | 0.082 |

| PSI评分 | 0.141 | 0.027 | 26.525 | 1.151 | 1.091~1.214 | <0.001 |

| SOFA评分 | 2.026 | 0.359 | 31.849 | 7.586 | 3.753~15.333 | <0.001 |

| 常量 | -16.847 | 3.744 | 20.247 | 0.000 | - | <0.001 |

| 注:PSI为肺炎严重指数评分,SOFA为序贯器官衰竭评分 | ||||||

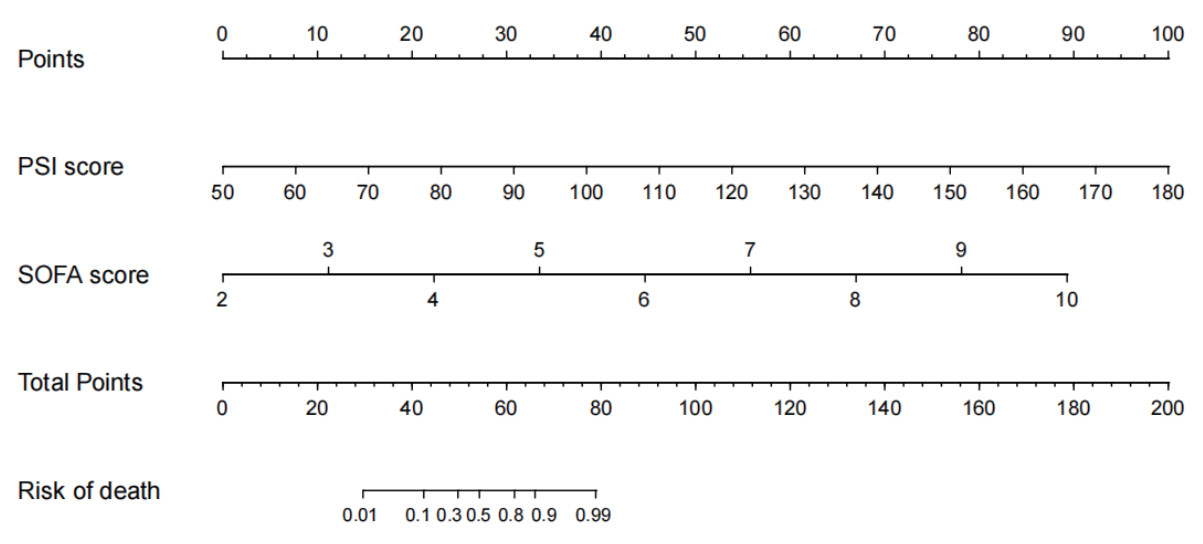

将上述2个独立危险因素纳入并成功建立老年CAP相关脓毒症患者预后的个体化列线图预测模型(图 2)。将每个变量对应分值相加得到总分,总分对应在最下方轴上的值即为患者死亡风险。

|

| 图 2 老年社区获得性肺炎相关脓毒症患者预后预测列线图模型 Fig 2 Nomogram model for prognosis prediction of elderly patients with sepsis associated with CAP |

|

|

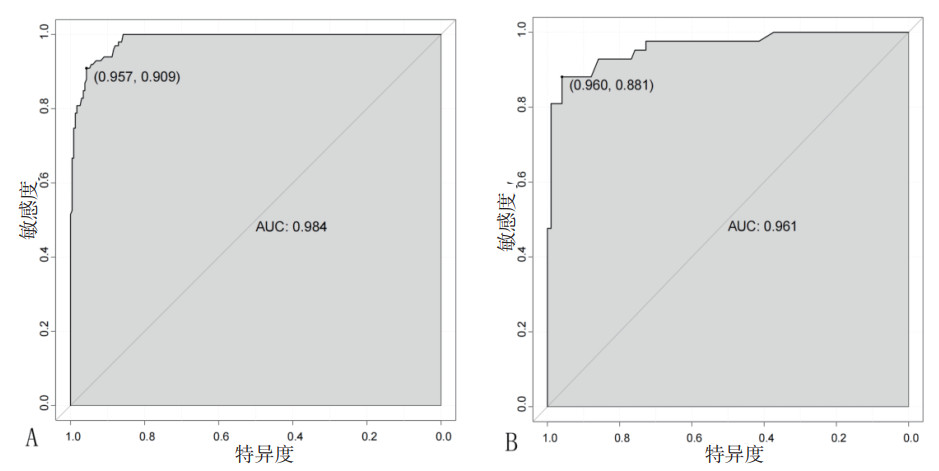

通过绘制两组人群的ROC曲线分析结果提示,预测模型在建模人群中预测价值曲线下面积(AUC)为0.984(95%CI: 0.975~0.994),敏感度为0.909,特异度为0.957(图 3A);在验证人群中AUC为0.961(95%CI: 0.926~0.996),敏感度为0.881,特异度为0.960(图 3B),表明预测模型具有良好的区分度。

|

| 图 3 预测模型在建模和验证人群中的ROC曲线 Fig 3 ROC curves of the prediction model in the modeling and validation groups |

|

|

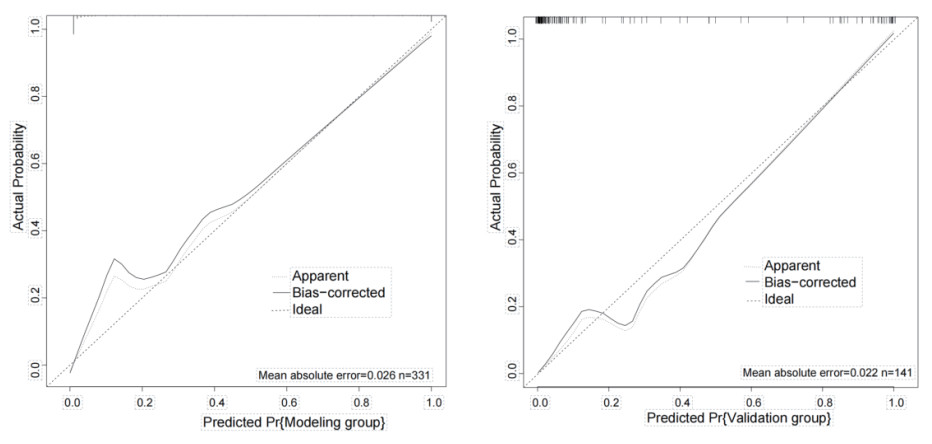

校准曲线结果显示,两组人群的平均绝对误差(MAE)分别为0.026和0.022,均方误差(MSE)分别为0.00168和0.00109(MAE和MSE值越小,说明校准度越高),表明预测模型具有较高的校准度(图 4)。

|

| 图 4 预测模型在建模和验证人群中的校准曲线 Fig 4 Calibration curve of the prediction model in the modeling and validation groups |

|

|

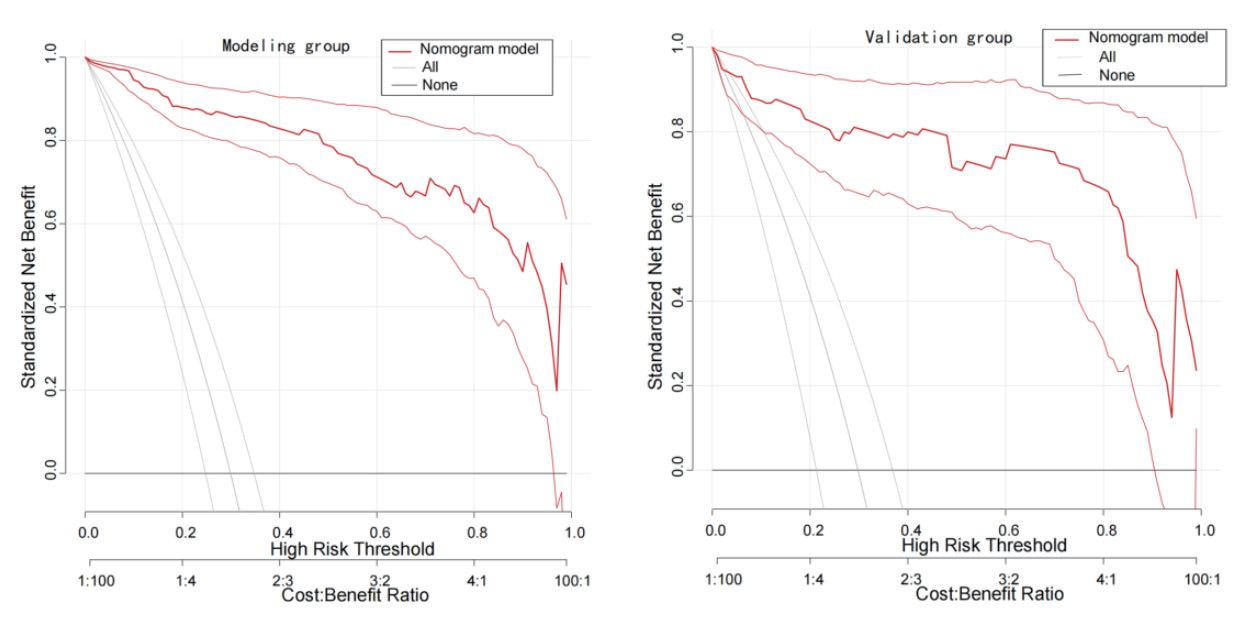

DCA曲线结果提示,该模型在建模人群和验证人群中的临床效益均优于“所有”(假设所有患者均死亡)或“无”(假设所有患者均没有死亡)曲线(图 5)。

|

| 图 5 预测模型在建模和验证人群中的决策曲线 Fig 5 Decision curve of the prediction model in the modeling and validation groups |

|

|

CAP是指患者在医院外因感染各种细菌、病毒、支原体等导致肺实质炎症[11]。当病情逐渐发展时,可出现器官功能障碍,严重时可导致脓毒症[12]。严重脓毒症是一个世界性的健康问题,在美国至少有三分之一的CAP患者因严重脓毒症而来到医院[13]。延误治疗可能导致严重后果,甚至死亡,这在老年患者中更甚[14]。初步确定老年CAP相关脓毒症的严重程度很重要,以便采取不同的管理和监测措施[15]。因此本研究旨在建立预测老年CAP相关脓毒症患者预后的列线图模型,以帮助老年CAP相关脓毒症患者的管理和治疗。

PSI评分和CURB-65评分是CAP患者预后的预测模型,同时也有助于指导新型冠状病毒肺炎治疗策略[16]。根据Aujesky等[17]对PSI和CURB-65评分进行比较,CURB-65因其易于使用而成为PSI的潜在替代品;然而,CURB-65的有效性和安全性是不明确的,这使得它的利用价值降低。它的主要目的是预测病死率和识别可能适合门诊治疗的低风险患者,并已广泛应用于CAP患者[18]。本研究和Nguyen等[19]发表的文章在CAP或新型冠状病毒肺炎的条件下都支持这一结论。Elmoheen等[20]在多种族新型冠状病毒肺炎患者研究中证实PSI在预测30 d病死率方面的表现同样优于CURB-65(AUC分别为0.83、0.78)。SOFA评分是用于评估器官衰竭的评分系统之一,可以预测疾病的严重程度和结局[21-22]。由于危重患者通常有多器官功能障碍,SOFA评分已被广泛用于预测危重患者的临床结局,如预测慢性肝功能衰竭和血液系统恶性肿瘤患者的病死率[23-24]。在本研究中,SOFA评分同样证实是预测老年CAP相关脓毒症患者预后的有价值的工具。先前的研究证明SOFA在预测CAP相关脓毒症28 d病死率方面优于CURB-65、PSI、qSOFA和降钙素原,其AUROC为0.913[25],而Kim等[26]研究提示SOFA和qSOFA在预测CAP相关脓毒症28 d病死率的AUROC分别为0.83和0.81。Yang等[27]研究表明当SOFA评分的截断值为5(AUC=0.995)时,可以很好地预测新型冠状病毒肺炎患者的死亡风险。本研究在LASSO回归和多因素Logistic回归分析结果基础上进一步绘制了列线图预测模型,ROC曲线结果显示建模人群和验证人群的AUC分别为0.984和0.961;DCA曲线结果显示该预测模型的临床效益显著高于“所有患者均死亡”和“无患者死亡”两种极端假设;校准曲线也显示该模型预测曲线与矫正、理想曲线拟合较好。所以该模型对于老年CAP相关脓毒症患者预后的预测价值较好。

利益冲突 所有作者声明无利益冲突

作者贡献声明 房延儒、王兴义:研究设计、统计学分析、论文撰写和修改;杨立山:研究设计、论文审阅及修改;王聪、赵涛:负责数据收集及整理

| [1] | 中华医学会呼吸病学分会. 社区获得性肺炎诊断和治疗指南[J]. 中华结核和呼吸杂志, 2006, 29(10): 651-655. DOI:10.3760/j:issn:1001-0939.1999.04.003 |

| [2] | González-Castillo J, Martín-Sánchez FJ, Llinares P, et al. Guidelines for the management of community-acquired pneumonia in the elderly patient[J]. Rev Esp Quimioter, 2014, 27(1): 69-86. |

| [3] | Viasus D, Núñez-Ramos JA, Viloria SA, et al. Pharmacotherapy for community-acquired pneumonia in the elderly[J]. Expert Opin Pharmacother, 2017, 18(10): 957-964. DOI:10.1080/14656566.2017.1340940 |

| [4] | McLaughlin JM, Khan FL, Thoburn EA, et al. Rates of hospitalization for community-acquired pneumonia among US adults: a systematic review[J]. Vaccine, 2020, 38(4): 741-751. DOI:10.1016/j.vaccine.2019.10.101 |

| [5] | Singer M, Deutschman CS, Seymour CW, et al. The third international consensus definitions for sepsis and septic shock (sepsis-3)[J]. JAMA, 2016, 315(8): 801-810. DOI:10.1001/jama.2016.0287 |

| [6] | 张建国, 陶志敏. 脓毒症的临床治疗进展——历经新冠疫情的思考[J]. 中华急诊医学杂志, 2024, 33(2): 135-144. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.issn.1671-0282.2024.02.002 |

| [7] | 李小舟, 邱泽亮, 赵广阔, 等. 卡诺夫斯基健康状况量表评分对老年脓毒症患者预后的评估价值[J]. 中华急诊医学杂志, 2022, 31(11): 1451-1456. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.issn.1671-0282.2022.11.003 |

| [8] | Bermejo-Martin JF, Cilloniz C, Mendez R, et al. Lymphopenic community acquired pneumonia (L-CAP), an immunological phenotype associated with higher risk of mortality[J]. EBioMedicine, 2017, 24: 231-236. DOI:10.1016/j.ebiom.2017.09.023 |

| [9] | Nair GB, Niederman MS. Updates on community acquired pneumonia management in the ICU[J]. Pharmacol Ther, 2021, 217: 107663. DOI:10.1016/j.pharmthera.2020.107663 |

| [10] | Saxena P, Sehgal IS, Agarwal R, et al. Severe community-acquired pneumonia[M]//Soneja M, Khanna P. Infectious Diseases in the Intensive Care Unit. Singapore: Springer, 2020: 59-86.10.1007/978-981-15-4039-4_4 |

| [11] | Metlay JP, Waterer GW, Long AC, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of adults with community-acquired pneumonia. an official clinical practice guideline of the American Thoracic Society and Infectious Diseases Society of America[J]. Am J Respir Crit Care Med, 2019, 200(7): e45-e67. DOI:10.1164/rccm.201908-1581ST |

| [12] | 李彭, 谢丽华, 孙圣华, 等. 社区获得性肺炎合并脓毒症患者临床特征及死亡危险因素分析[J]. 中国呼吸与危重监护杂志, 2022, 21(4): 260-268. DOI:10.7507/1671-6205.202204009 |

| [13] | Blanco J, Muriel-Bombín A, Sagredo V, et al. Incidence, organ dysfunction and mortality in severe sepsis: a Spanish multicentre study[J]. Crit Care, 2008, 12(6): R158. DOI:10.1186/cc7157 |

| [14] | Lv CX, Li MY, Shi W, et al. Exploration of prognostic factors for prediction of mortality in elderly CAP population using a nomogram model[J]. Front Med, 2022, 9: 976148. DOI:10.3389/fmed.2022.976148 |

| [15] | Montull B, Menéndez R, Torres A, et al. Predictors of severe sepsis among patients hospitalized for community-acquired pneumonia[J]. PLoS One, 2016, 11(1): e0145929. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0145929 |

| [16] | Ilg A, Moskowitz A, Konanki V, et al. Performance of the CURB-65 score in predicting critical care interventions in patients admitted with community-acquired pneumonia[J]. Ann Emerg Med, 2019, 74(1): 60-68. DOI:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2018.06.017 |

| [17] | Aujesky D, Fine MJ. The pneumonia severity index: a decade after the initial derivation and validation[J]. Clin Infect Dis, 2008, 47(Suppl 3): S133-S139. DOI:10.1086/591394 |

| [18] | Chen YX, Li CS. Lactate on emergency department arrival as a predictor of mortality and site-of-care in pneumonia patients: a cohort study[J]. Thorax, 2015, 70(5): 404-410. DOI:10.1136/thoraxjnl-2014-206461 |

| [19] | Nguyen Y, Corre F, Honsel V, et al. Applicability of the CURB-65 pneumonia severity score for outpatient treatment of COVID-19[J]. J Infect, 2020, 81(3): e96-e98. DOI:10.1016/j.jinf.2020.05.049 |

| [20] | Elmoheen A, Abdelhafez I, Salem W, et al. External validation and recalibration of the CURB-65 and PSI for predicting 30-day mortality and critical care intervention in multiethnic patients with COVID-19[J]. Int J Infect Dis, 2021, 111: 108-116. DOI:10.1016/j.ijid.2021.08.027 |

| [21] | Jones AE, Trzeciak S, Kline JA. The Sequential Organ Failure Assessment score for predicting outcome in patients with severe sepsis and evidence of hypoperfusion at the time of emergency department presentation[J]. Crit Care Med, 2009, 37(5): 1649-1654. DOI:10.1097/CCM.0b013e31819def97 |

| [22] | Chen SJ, Chao TF, Chiang MC, et al. Prediction of patient outcome from Acinetobacter baumannii bacteremia with sequential organ failure assessment (SOFA) and acute physiology and chronic health evaluation (APACHE) Ⅱ scores[J]. Intern Med, 2011, 50(8): 871-877. DOI:10.2169/internalmedicine.50.4312 |

| [23] | Demandt AMP, Geerse DA, Janssen BJP, et al. The prognostic value of a trend in modified SOFA score for patients with hematological malignancies in the intensive care unit[J]. Eur J Haematol, 2017, 99(4): 315-322. DOI:10.1111/ejh.12919 |

| [24] | Pan HC, Jenq CC, Tsai MH, et al. Scoring systems for 6-month mortality in critically ill cirrhotic patients: a prospective analysis of chronic liver failure - sequential organ failure assessment score (CLIF-SOFA)[J]. Aliment Pharmacol Ther, 2014, 40(9): 1056-1065. DOI:10.1111/apt.12953 |

| [25] | Zhou HJ, Guo SB, Lan TF, et al. Risk stratification and prediction value of procalcitonin and clinical severity scores for community-acquired pneumonia in ED[J]. Am J Emerg Med, 2018, 36(12): 2155-2160. DOI:10.1016/j.ajem.2018.03.050 |

| [26] | Kim MW, Lim JY, Oh SH. Mortality prediction using serum biomarkers and various clinical risk scales in community-acquired pneumonia[J]. Scand J Clin Lab Invest, 2017, 77(7): 486-492. DOI:10.1080/00365513.2017.1344298 |

| [27] | Yang Z, Hu QM, Huang F, et al. The prognostic value of the SOFA score in patients with COVID-19: a retrospective, observational study[J]. Medicine, 2021, 100(32): e26900. DOI:10.1097/MD.0000000000026900 |

2024, Vol. 33

2024, Vol. 33