2. 西湖大学医学院附属杭州市第一人民医院重症医学科,杭州 310006;

3. 浙江中医药大学第四临床医学院,杭州 310053;

4. 浙江大学医学院附属第二医院重症医学科,杭州 310009;

5. 宁海县第一医院重症医学科,宁波 315600

2. Department of Critical Care Medicine, Hangzhou First People' s Hospital Affiliated to Westlake University School of Medicine, Hangzhou 310006, China;

3. The Fourth Clinical School of Zhejiang Chinese Medicine University, Hangzhou 310053, China;

4. Department of Critical Care Medicine, Second Affiliated Hospital Zhejiang University School of Medicine, Hangzhou 310009, China;

5. Department of Critical Care Medicine, Ninghai First Hospital, Ningbo 315600, China

心脏骤停(cardiac arrest, CA)是成人猝死的主要原因,在发达国家的生存率仅9.1%~18.8%[1]。CA的高死亡率和高致残率是医学亟待解决的问题。随着体外生命支持技术的成熟,静脉-动脉体外膜肺氧合(veno-arterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, VA-ECMO)为难治性CA和心源性休克的患者提供持续的体外循环支持[2],使出院生存率得到了一定程度的提高[3-4]。CA患者的神经预后评估应是多元化的[5-6],而临床检查如脑干反射、运动反应等易受镇静镇痛药物的干扰,影像学检查也总是难以实现[7-8]。生物标志物因其易于获取和检测而受到广泛的研究[9],其中神经元特异性烯醇化酶(neuron-specific enolase, NSE)作为神经元损伤的产物,是唯一推荐用于复苏患者预后评估的生物标志物[5]。目前研究多关注NSE在传统心肺复苏患者中的预后价值[10],仅几项研究对NSE与体外膜肺氧合(extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, ECMO)支持下CA患者神经系统结局的关系进行了阐述[11-15],但仍有不足,并且国内外指南尚未对这种情况下的预后评估做出建议[5, 16]。因此,本研究旨在探索血清NSE水平与VA-ECMO支持下CA患者不良神经系统结局之间的关联性。

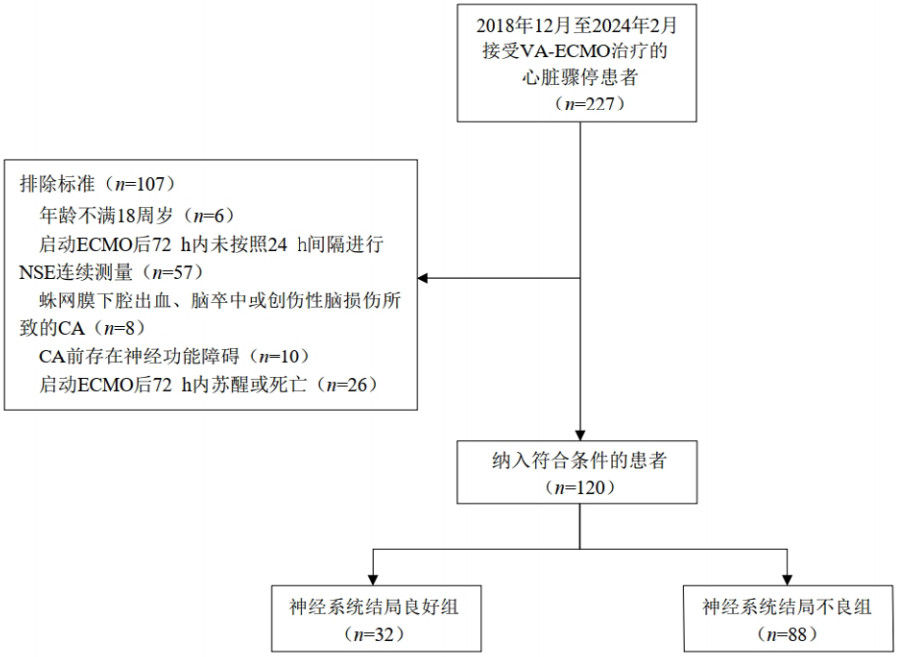

1 资料与方法 1.1 研究对象本研究为多中心回顾性研究,选取2018年12月至2024年2月浙江省杭州市两家医院(西湖大学医学院附属杭州市第一人民医院、浙江大学医学院附属第二医院)收住的因难治性CA或心源性休克而接受VA-ECMO支持的CA患者。排除标准为:(1)年龄不满18周岁;(2)启动ECMO后72 h内未按照24 h的间隔进行NSE连续测量;(3)CA前存在神经功能障碍;(4)蛛网膜下腔出血、脑卒中或创伤性脑损伤所致的CA;(5)启动ECMO后存活时长不足72 h。本研究经西湖大学医学院附属杭州市第一人民医院伦理委员会审查通过,批准文号:IIT-20230420-0077-01。

1.2 临床资料收集收集患者相关临床资料,包括人口统计信息、CA地点、目击者、旁观者心肺复苏、电除颤、CA到ECMO启动时间、ECMO参数、合并症、生命体征、实验室检查、治疗、评分等。NSE在纳入研究的两家医院中是实验室常规开展检测的项目,均使用标准的NSE定量检测试剂盒(荧光免疫分析法,上海透景生命科技股份有限公司,中国)。在启动ECMO后的24、48、72 h连续采集血液样本,定量评估血清NSE的水平。凡提示溶血的样本则被排除。

使用格拉斯哥-匹兹堡脑功能表现分级(cerebral performance category, CPC)表示出院时的神经系统功能状态,将患者分为神经系统结局良好组(CPC 1~2级)和神经系统结局不良组(CPC 3~5级)[17]。

1.3 ECMO管理由专业的ECMO团队判定指征,并提出启动VA-ECMO的决策。传统心肺复苏20 min后无自主循环恢复(return of spontaneous circulation, ROSC),或复苏成功但出现难治性心源性休克或自主心律不能维持的情况下,可启动VA-ECMO。VA-ECMO的植入按照指南标准执行[18],一般从股血管通路进行置管。ECMO转机后,由专业的ECMO诊疗中心负责患者的规范化管理。床旁心脏超声评估心功能恢复、泵支持强度下降、不使用或低剂量儿茶酚胺维持下血流动力学稳定时,考虑撤机。脱机试验成功后进行拔管。另外,治疗无效、严重并发症、放弃继续生命支持治疗时,则撤除VA-ECMO。

1.4 统计学方法采用SPSS软件(25.0版)和R软件(4.3.2版)对数据进行分析。使用Kolmogorov-Smirnov检验来确定连续变量的正态性,将连续变量根据是否符合正态分布分别表示为均数±标准差(x±s)或中位数(四分位数)[M(Q1, Q3)],使用独立样本t检验或Mann-Whitney U检验进行比较。分类变量表示为频数(百分数),使用卡方检验或Fisher精确检验进行比较。比较CA患者神经系统结局良好组和不良组之间临床数据以及24、48、72 h血清NSE水平的差异。绘制受试者工作特征曲线(receiver operating characteristic curve, ROC)评估不同时段的血清NSE水平对预测CA患者不良神经系统结局的准确性,评价指标包括曲线下面积(area under the curve, AUC)、敏感度、特异度和Youden指数。计算Youden指数最大时对应的血清NSE水平为最佳截断值。使用单因素联合多因素逻辑回归分析各变量与VA-ECMO支持下CA患者不良神经系统结局的关系,并以年龄、性别、CA地点、体外心肺复苏(extracorporeal cardiopulmonary resuscitation, ECPR)情况进行亚组分析。以P < 0.05为差异具有统计学意义。

2 结果 2.1 纳入患者的一般临床资料经筛选,共有120例符合条件的CA患者纳入本研究(图 1)。其中88例(73.3%)神经系统结局不良(CPC 3~5级),32例(26.7%)神经系统结局良好(CPC 1~2级),42例(35.0%)在出院时死亡(CPC 5)级。85例(70.8%)为院内CA,86例(71.7%)为心源性CA,37例(30.8%)为ECPR。

|

| 注:VA-ECMO为动静脉体外膜肺氧合,CA为心脏骤停 图 1 纳入患者流程图 Fig 1 Flowchart of inclusion patients |

|

|

两组比较显示,神经系统结局不良组患者的除颤、连续性肾脏替代治疗(continuous renal replacement therapy, CRRT)比例、凝血酶原时间、国际标准化比值、肌酐、乳酸、序贯器官衰竭评分(sequential organ failure assessment, SOFA)和急性生理与慢性健康评分(acute physiology and chronic health evaluation, APACHEⅡ)均高于良好组,而血小板计数、格拉斯哥昏迷评分(Glasgow coma scale, GCS)均低于良好组。其他变量在两组之间差异无统计学意义。不良组患者的重症监护室(intensive care unit, ICU)住院时长较良好组短。见表 1。

| 变量 | 全体(n=120) | 良好组(n=32) | 不良组(n=88) | 统计值 | P值 |

| 一般情况 | |||||

| 年龄(岁) a | 52.28±15.53 | 50.88±12.20 | 52.80±16.61 | -0.687 | 0.493 |

| 男性b | 89 (74.2) | 22 (68.8) | 67 (76.1) | 0.671 | 0.414 |

| 合并症b | |||||

| 高血压 | 47 (39.2) | 11 (34.4) | 36 (40.9) | 0.422 | 0.517 |

| 糖尿病 | 21 (17.5) | 2 (6.3) | 19 (21.6) | 3.829 | 0.050 |

| 冠状动脉粥样硬化性心脏病 | 52 (43.3) | 13 (40.6) | 39 (44.3) | 0.133 | 0.718 |

| 慢性心力衰竭 | 27 (22.5) | 5 (15.6) | 22 (25.0) | 1.184 | 0.277 |

| 恶性肿瘤 | 7 (5.8) | 3 (94) | 4 (4.6) | 0.307 | 0.577 |

| CA特点b | |||||

| 院外CA | 35 (29.2) | 9 (28.1) | 26 (29.6) | 0.018 | 0.880 |

| 有目击者 | 120 (100) | 32 (100) | 88 (100) | - | - |

| 旁观者心肺复苏 | 106 (88.3) | 30 (93.8) | 76 (86.4) | 0.634 | 0.428 |

| 除颤 | 65 (54.2) | 24 (75.0) | 41 (46.6) | 7.625 | 0.006 |

| 治疗手段b | |||||

| 经皮冠状动脉介入治疗 | 42 (35.0) | 12 (37.5) | 30 (34.1) | 0.121 | 0.729 |

| 连续肾脏替代治疗 | 95 (79.2) | 20 (62.5) | 75 (85.2) | 7.348 | 0.007 |

| 主动脉内球囊反搏 | 44 (36.7) | 9 (28.1) | 35 (39.8) | 1.370 | 0.242 |

| 目标体温管理 | 111 (92.5) | 29 (90.6) | 82 (93.2) | 0.008 | 0.938 |

| 生命体征a | |||||

| 心率(次/min) | 97.27±18.02 | 97.89±20.10 | 96.97±17.53 | 0.121 | 0.903 |

| 收缩压(mmHg) | 114.61±12.36 | 111.89±9.85 | 115.89±13.43 | -0.801 | 0.433 |

| 舒张压(mmHg) | 74.77±9.92 | 70.56±7.95 | 76.76±10.31 | -1.588 | 0.124 |

| 平均动脉压(mmHg) | 86.14±8.22 | 83.15±8.32 | 87.55±7.99 | -1.344 | 0.190 |

| 呼吸频率(次/min) | 17.02±5.52 | 16.11±1.41 | 17.45±6.64 | -0.593 | 0.559 |

| 实验室检查c | |||||

| 血红蛋白(g/L) | 94.00 (77.00, 116.00) | 104.00 (85.50, 126.50) | 91.50 (73.00, 115.00) | -1.566 | 0.117 |

| 白细胞(×109/L) | 14.80 (10.10, 18.90) | 14.80 (12.00, 20.20) | 14.85 (9.33, 18.88) | -0.694 | 0.489 |

| 血小板(×109/L) | 120.00 (82.00, 176.00) | 140.00 (112.50, 198.00) | 113.50 (64.25, 171.25) | -1.991 | 0.047 |

| 凝血酶原时间(s) | 19.20 (16.50, 25.15) | 17.40 (15.55, 22.75) | 19.80 (16.93, 25.40) | -2.191 | 0.029 |

| 国际标准化比值 | 1.69 (1.34, 2.32) | 1.46 (1.28, 1.94) | 1.74 (1.38, 2.35) | -2.087 | 0.036 |

| 胆红素(μmol/L) | 18.90 (12.40, 37.60) | 16.80 (12.10, 22.55) | 19.35 (12.65, 45.67) | -1.689 | 0.091 |

| 肌酐(μmol/L) | 145.00 (101.00, 184.00) | 116.00 (84.50, 171.00) | 151.00 (107.50, 185.00) | -2.200 | 0.028 |

| 乳酸(mmol/L) | 8.89 (5.60, 13.80) | 7.50 (4.01, 10.04) | 10.50 (6.10, 14.40) | -2.000 | 0.045 |

| 氧分压(mmHg) | 195.60 (102.30, 331.50) | 217.40 (112.75, 339.60) | 195.25 (103.28, 303.65) | -0.522 | 0.606 |

| 二氧化碳分压(mmHg) | 31.70 (27.20, 37.70) | 30.80 (24.95, 34.95) | 32.10 (27.68, 38.72) | -0.991 | 0.320 |

| 实际碳酸氢盐(mmol/L) | 18.80 (15.10, 21.70) | 19.10 (16.80, 21.05) | 17.85 (14.30, 21.93) | -0.655 | 0.507 |

| ECMO参数c | |||||

| CA至ECMO启动时间(min) | 89.00 (62.00, 177.00) | 85.00 (63.50, 138.00) | 98.00 (62.75, 184.75) | -0.991 | 0.325 |

| 持续时间(d) | 5.21 (3.96, 7.78) | 4.71 (3.96, 6.98) | 5.29 (3.98, 8.25) | -0.466 | 0.637 |

| 初始泵流量(L/min) | 3.20 (2.90, 3.60) | 3.25 (2.91, 3.70) | 3.20 (2.90, 3.50) | -0.063 | 0.956 |

| 初始气流量(L/min) | 3.00 (3.00, 4.00) | 3.50 (3.00, 5.00) | 3.00 (3.00, 4.00) | -0.172 | 0.866 |

| 初始转速(r/min) | 3 500.00 (3 060.00, 3 820.00) | 3 620.00 (3 325.50, 4 057.50) | 3 500.00 (3 001.25, 3 742.50) | -0.207 | 0.227 |

| 评分c | |||||

| GCS评分 | 3.00 (3.00, 3.00) | 3.00 (3.00, 5.00) | 3.00 (3.00, 3.00) | -3.114 | 0.002 |

| SOFA评分 | 12.00 (11.00, 16.00) | 11.00 (9.00, 12.00) | 13.00 (11.00, 16.00) | -3.329 | < 0.001 |

| APACHEⅡ评分 | 29.00 (25.00, 35.00) | 25.00 (22.00, 31.00) | 30.00 (26.00, 37.75) | -3.353 | < 0.001 |

| NSE (μg/L) c | |||||

| 24 h | 67.72 (41.88, 129.05) | 43.60 (32.96, 59.90) | 88.10 (56.60, 164.03) | -4.471 | < 0.001 |

| 48 h | 88.53 (36.61, 201.45) | 33.65 (24.30, 48.12) | 121.70 (63.91, 255.57) | -6.199 | < 0.001 |

| 72 h | 103.75 (32.10, 287.48) | 24.25 (20.29, 34.00) | 159.05 (76.90, 326.50) | -6.862 | < 0.001 |

| 注:CA为心脏骤停,ECMO为体外膜肺氧合,GCS为格拉斯哥昏迷评分,SOFA为序贯器官衰竭评分,APACHE Ⅱ为急性生理与慢性健康评分,NSE为神经元特异性烯醇化酶;a为x±s,b为例(%),c为M(Q1,Q3) | |||||

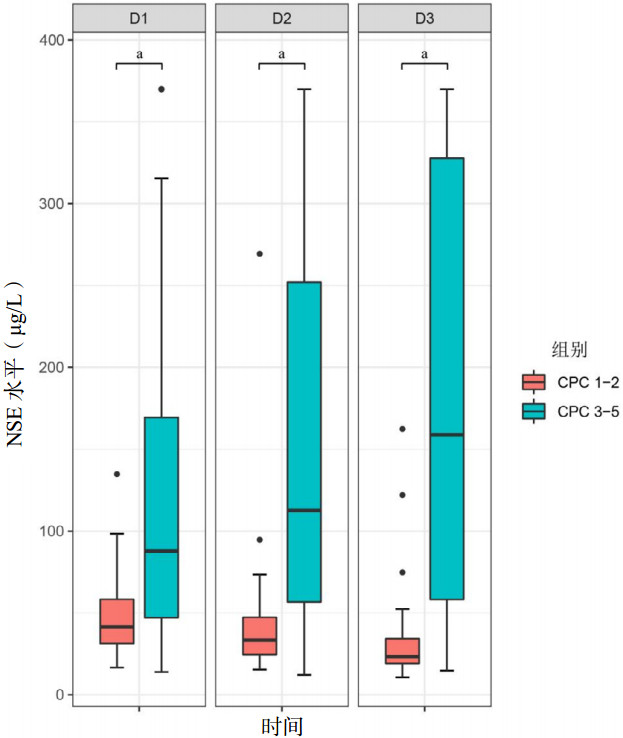

如表 1和图 2所示,VA-ECMO转机后24、48、72 h的血清NSE水平在神经系统结局不良组和良好组之间均差异有统计学意义(均P < 0.001),不良组的NSE水平明显高于良好组。

|

| 图 2 两组患者血清NSE水平的箱形图 Fig 2 Boxplots of serum NSE levels in the two groups |

|

|

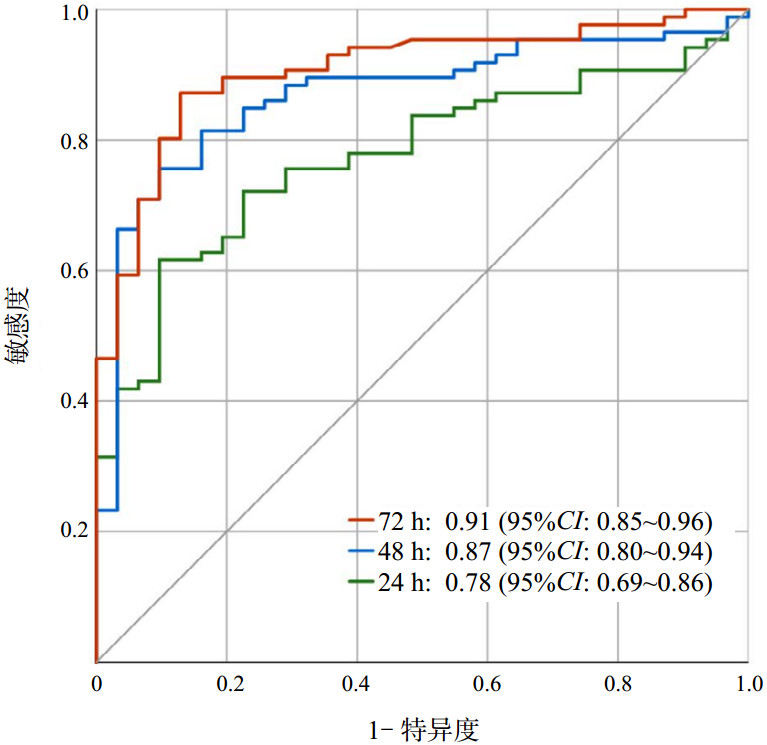

ROC曲线展示了不同时段的血清NSE水平预测VA-ECMO支持下CA患者不良结局的准确性,见图 3和表 2。72 h NSE水平的AUC为0.91(95%CI: 0.85~0.96),48 h的AUC为0.87(95%CI: 0.80~0.94),24 h的AUC为0.78(95%CI: 0.69~0.86)。DeLong检验显示,72 h NSE在预测神经系统不良结局方面优于48 h和24 h(均P < 0.05)。Youden指数最大时的血清NSE水平确定为最佳截断值,72 h为42.0 μg/L,48 h为64.5 μg/L,24 h为70.6 μg/L。

|

| 图 3 不同时段NSE预测不良结局的ROC曲线 Fig 3 ROC curves of NSE predicting poor outcomes at different time periods |

|

|

| 指标 | AUC (95%CI) | 截断值 | Youden指数 | 敏感度(95%CI) | 特异度(95%CI) |

| 24 h NSE | 0.78 (0.69~0.86) | 70.6 | 0.49 | 0.87 (0.70~0.96) | 0.62 (0.51~0.72) |

| 48 h NSE | 0.87 (0.80~0.94) | 64.5 | 0.66 | 0.90 (0.74~0.98) | 0.76 (0.65~0.84) |

| 72 h NSE | 0.91 (0.85~0.96) | 42.0 | 0.74 | 0.87 (0.70~0.96) | 0.87 (0.78~0.93) |

| 注:AUC为曲线下面积,NSE为神经元特异性烯醇化酶 | |||||

多因素逻辑回归对表 1中P < 0.05的变量与VA-ECMO支持下CA患者不良神经系统结局之间的关系进行了分析,结果显示,仅72 h的血清NSE水平与不良结局有关(P < 0.05),而与48 h和24 h的NSE水平无关。72 h NSE > 42.0 μg/L是预测不良结局的独立危险因素,OR=20.29(95%CI: 2.90~92.15)。见表 3。

| 变量 | β | S.E | Z | P值 | OR (95%CI) |

| 72 h NSE > 42.0 μg/L | 3.01 | 0.99 | 3.03 | 0.002 | 20.29 (2.90~92.15) |

| 48 h NSE > 64.5 μg/L | 0.25 | 1.17 | 0.21 | 0.834 | 1.28 (0.13~12.75) |

| 24 h NSE > 70.6 μg/L | 1.25 | 1.13 | 1.11 | 0.265 | 3.51 (0.39~31.85) |

| 除颤 | -0.86 | 0.83 | -1.04 | 0.300 | 0.42 (0.08~2.15) |

| CRRT | 0.11 | 1.12 | 0.10 | 0.919 | 1.12 (0.12~10.07) |

| 血小板 | 0.00 | 0.00 | -0.07 | 0.943 | 1.00 (0.99~1.01) |

| 凝血酶原时间 | -0.12 | 0.32 | -0.37 | 0.713 | 0.89 (0.48~1.66) |

| 国际标准化比值 | 1.85 | 3.35 | 0.55 | 0.581 | 6.34 (0.11~46.94) |

| 肌酐 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.30 | 0.767 | 1.00 (0.99~1.02) |

| 乳酸 | -0.12 | 0.08 | -1.42 | 0.154 | 0.89 (0.75~1.05) |

| GCS评分 | -0.40 | 0.29 | -1.37 | 0.169 | 0.67 (0.38~1.19) |

| SOFA评分 | 0.16 | 0.16 | 1.04 | 0.300 | 1.18 (0.86~1.61) |

| APACHEⅡ评分 | 0.02 | 0.06 | 0.39 | 0.697 | 1.02 (0.91~1.16) |

| 注:NSE为神经元特异性烯醇化酶,APACHE Ⅱ为急性生理与慢性健康评分,SOFA为序贯器官衰竭评分,GCS为格拉斯哥昏迷评分,CRRT为连续性肾脏替代治疗 | |||||

以年龄、性别、CA地点、ECPR进行亚组分析,结果显示(表 4),在年龄≥60岁的患者中,ECMO启动后72 h的血清NSE水平与CA患者神经系统不良结局无关(P > 0.05)。在年龄 < 60岁、男性或女性、院外或院内CA、是否进行ECPR的患者中,72 h的血清NSE水平是CA患者神经系统不良结局的独立危险因素(均P < 0.05),且各个亚组与NSE之间不存在交互作用。

| 变量 | 例(%) | OR (95%CI) | P值 | P交互值 |

| 年龄 | 0.097 | |||

| < 60岁 | 84 (70.0) | 1.05 (1.02~1.08) | < 0.001 | |

| ≥60岁 | 36 (30.0) | 1.02 (1.00~1.04) | 0.100 | |

| 性别 | 0.299 | |||

| 男性 | 32 (36.7) | 1.02 (1.00~1.05) | 0.039 | |

| 女性 | 88 (73.3) | 1.04 (1.02~1.07) | 0.001 | |

| CA地点 | 0.338 | |||

| 院外 | 35 (29.2) | 1.02 (1.00~1.05) | 0.026 | |

| 院内 | 85 (70.8) | 1.04 (1.02~1.06) | < 0.001 | |

| ECPR | 0.229 | |||

| 否 | 83 (69.2) | 1.04 (1.02~1.07) | 0.001 | |

| 是 | 37 (30.8) | 1.02 (1.00~1.04) | 0.046 | |

| 注:CA为心脏骤停,ECPR为体外心肺复苏 | ||||

心肺复苏后患者的预后评估对于及时调整诊疗策略、合理配置医疗资源、改善整体生存率具有重要意义。预后评估应当是多模态的,包括体格检查、生物标志物以及影像学等手段。但是由于镇静药物的干扰、技术原因的限制等多种因素,仅血清生物标志物能提供相对稳定而准确的预后评估[6-7]。NSE是目前唯一推荐用于CA患者预后评估的生物标志物。指南认为48 h或72 h NSE > 60 μg/L与CA患者的不良神经系统结局有关[5]。但对于VA-ECMO支持下CA患者的神经功能评估,指南尚未做出明确的建议。

已有一些研究探索了血清NSE水平与VA-ECMO支持下CA患者不良预后的关联。Schrage等[15]在129例ECPR患者中,发现48 h的血清NSE水平辨别不良结局的能力最强,AUC为0.87,截断值为70 μg/L。但这项研究的结局分组标准有所不同,认为CPC评分3分的患者尚有神经康复的希望而纳入预后良好组。Floerchinger等[14]在134例的ECPR患者中,同样确定48 h的血清NSE水平是预测脑损伤和住院病死率的最佳选择,AUC分别为0.733和0.737,但这项研究使用脑部CT来评价神经功能而不是CPC评分。而Kim等[11]在ECPR患者的研究中,发现72 h的NSE水平区分不良预后的能力最强,AUC为0.897,截断值为53.2 μg/L。但这项研究的样本量仅25例,无法代表整个ECPR人群,因此存在较大偏倚。此外,Reuter等[12]前瞻性地研究了103例VA-ECMO支持下CA患者的NSE水平与不良结局之间的关系,认为第3天的NSE > 25 μg/L与28 d的病死率和90 d的不良功能预后独立相关,而第1天和第7天的NSE水平则与之无关。Brodska等[19]对Prague-OHCA试验展开了事后分析,其中包括使用NSE对92例ECPR患者180 d的神经预后进行评估,结果发现48 h和72 h的NSE水平在神经预后良好组和不良组之间差异有统计学意义,区分预后良好的AUC均为0.9,截断值分别为61.3 μg/L和56.9 μg/L,而24 h的NSE水平在两组之间差异无统计学意义。

本项多中心研究在浙江省杭州市的两家三级医院内展开,旨在探索血清NSE水平与VA-ECMO支持下CA患者不良神经系统结局之间的关联性。首先,本研究通过多因素逻辑回归分析,发现72 h的血清NSE水平与不良的神经系统结局相关(P < 0.05),并且预测价值最高,AUC为0.91(95%CI: 0.85~0.96)。与先前的一些研究不同,本研究发现24 h和48 h的NSE与不良结局之间并不相关(P > 0.05)。其次,本研究通过计算Youden指数的最大值确定最佳截断值为42.0 μg/L,并且72 h NSE > 42.0 μg/L是预测不良结局的独立危险因素(OR=20.29,95%CI: 2.90~92.15)。

本研究也存在一些局限性。第一,NSE是存在于神经元细胞、红细胞、血小板中的一种生物酶[20-21],ECMO运行导致的溶血可能会影响血清NSE的水平[22]。研究认为前12 h内的溶血很大程度上损害了NSE测量值的可靠性[23];但也有研究认为VA-ECMO期间潜在的溶血不会显著影响NSE的预后价值[24]。第二,ECMO的适应症限制了它在CA患者体外生命支持中的应用,致使病例数远少于传统复苏的CA患者,因此仍存在样本量偏小的问题。第三,由于ECPR患者只占30.8 %,虽然亚组分析结果显示无论是否进行ECPR,血清NSE水平升高都是不良神经预后的独立预测因素,但非ECPR患者从ROSC到ECMO启动之间的时间间隔各异,这可能影响初始NSE数值,因此需要更大的ECPR队列开展进一步研究。第四,这是一项回顾性研究,非盲法的数据收集可能导致偏倚。第五,虽然NSE易于获取并相对准确,但预后评估仍应该是多模态的。

综上,本研究发现72 h的血清NSE水平升高与VA-ECMO支持下的CA患者的不良神经系统结局有关,为确定NSE的预后价值提供了支持,未来仍需要更大规模的、前瞻性的研究进行验证。

利益冲突 所有作者声明无利益冲突

作者贡献声明 倪培峰:数据收集、统计学分析、论文撰写;张伟东,张根生,陈启江:数据收集及整理;刁孟元,胡炜,朱英:研究设计、论文修改

| [1] | Tsao CW, Aday AW, Almarzooq ZI, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics-2023 update: a report from the American heart association[J]. Circulation, 2023, 147(8): e93-e621. DOI:10.1161/CIR.0000000000001123 |

| [2] | Burrell A, Kim J, Alliegro P, et al. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for critically ill adults[J]. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 2023, 9(9): CD010381. DOI:10.1002/14651858.CD010381.pub3 |

| [3] | Low CJW, Ramanathan K, Ling RR, et al. Extracorporeal cardiopulmonary resuscitation versus conventional cardiopulmonary resuscitation in adults with cardiac arrest: a comparative meta-analysis and trial sequential analysis[J]. Lancet Respir Med, 2023, 11(10): 883-893. DOI:10.1016/S2213-2600(23)00137-6 |

| [4] | Holmberg MJ, Granfeldt A, Guerguerian AM, et al. Extracorporeal cardiopulmonary resuscitation for cardiac arrest: an updated systematic review[J]. Resuscitation, 2023, 182: 109665. DOI:10.1016/j.resuscitation.2022.12.003 |

| [5] | Nolan JP, Sandroni C, Böttiger BW, et al. European resuscitation council and European society of intensive care medicine guidelines 2021: post-resuscitation care[J]. Intensive Care Med, 2021, 47(4): 369-421. DOI:10.1007/s00134-021-06368-4 |

| [6] | Rossetti AO, Rabinstein AA, Oddo M. Neurological prognostication of outcome in patients in Coma after cardiac arrest[J]. Lancet Neurol, 2016, 15(6): 597-609. DOI:10.1016/S1474-4422(16)00015-6 |

| [7] | Sandroni C, D'Arrigo S, Cacciola S, et al. Prediction of poor neurological outcome in comatose survivors of cardiac arrest: a systematic review[J]. Intensive Care Med, 2020, 46(10): 1803-1851. DOI:10.1007/s00134-020-06198-w |

| [8] | Ben-Hamouda N, Ltaief Z, Kirsch M, et al. Neuroprognostication under ECMO after cardiac arrest: are classical tools still performant?[J]. Neurocrit Care, 2022, 37(1): 293-301. DOI:10.1007/s12028-022-01516-0 |

| [9] | Song H, Bang HJ, You Y, et al. Novel serum biomarkers for predicting neurological outcomes in postcardiac arrest patients treated with targeted temperature management[J]. Crit Care, 2023, 27(1): 113. DOI:10.1186/s13054-023-04400-1 |

| [10] | Kurek K, Swieczkowski D, Pruc M, et al. Predictive performance of neuron-specific enolase (NSE) for survival after resuscitation from cardiac arrest: a systematic review and meta-analysis[J]. J Clin Med, 2023, 12(24): 7655. DOI:10.3390/jcm12247655 |

| [11] | Kim HB, Yang JH, Lee YH. Are serial neuron-specific enolase levels associated with neurologic outcome of ECPR patients: a retrospective multicenter observational study[J]. Am J Emerg Med, 2023, 69: 58-64. DOI:10.1016/j.ajem.2023.03.047 |

| [12] | Reuter J, Peoc'h K, Bouadma L, et al. Neuron-specific enolase levels in adults under venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation[J]. Crit Care Explor, 2020, 2(10): e0239. DOI:10.1097/CCE.0000000000000239 |

| [13] | Petermichl W, Philipp A, Hiller KA, et al. Reliability of prognostic biomarkers after prehospital extracorporeal cardiopulmonary resuscitation with target temperature management[J]. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med, 2021, 29(1): 147. DOI:10.1186/s13049-021-00961-8 |

| [14] | Floerchinger B, Philipp A, Camboni D, et al. NSE serum levels in extracorporeal life support patients-Relevance for neurological outcome?[J]. Resuscitation, 2017, 121: 166-171. DOI:10.1016/j.resuscitation.2017.09.001 |

| [15] | Schrage B, Rübsamen N, Becher PM, et al. Neuron-specific-enolase as a predictor of the neurologic outcome after cardiopulmonary resuscitation in patients on ECMO[J]. Resuscitation, 2019, 136: 14-20. DOI:10.1016/j.resuscitation.2019.01.011 |

| [16] | 心肺复苏后昏迷患者早期神经功能预后评估专家共识组. 心肺复苏后昏迷患者早期神经功能预后评估专家共识[J]. 中华急诊医学杂志, 2019, 28(2): 156-162. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.issn.1671-0282.2019.02.006 |

| [17] | Edgren E, Hedstrand U, Kelsey S, et al. Assessment of neurological prognosis in comatose survivors of cardiac arrest. BRCT I Study Group[J]. Lancet, 1994, 343(8905): 1055-1059. DOI:10.1016/s0140-6736(94)90179-1 |

| [18] | Gajkowski EF, Herrera G, Hatton L, et al. ELSO guidelines for adult and pediatric extracorporeal membrane oxygenation circuits[J]. ASAIO J, 2022, 68(2): 133-152. DOI:10.1097/MAT.0000000000001630 |

| [19] | Brodska H, Smalcova J, Kavalkova P, et al. Biomarkers for neuroprognostication after standard versus extracorporeal cardiopulmonary resuscitation - A sub-analysis of Prague-OHCA study[J]. Resuscitation, 2024, 199: 110219. DOI:10.1016/j.resuscitation.2024.110219 |

| [20] | Schmechel D, Marangos PJ, Zis AP, et al. Brain endolases as specific markers of neuronal and glial cells[J]. Science, 1978, 199(4326): 313-315. DOI:10.1126/science.339349 |

| [21] | Day IN, Thompson RJ. Levels of immunoreactive aldolase C, creatine kinase-BB, neuronal and non-neuronal enolase, and 14-3-3 protein in circulating human blood cells[J]. Clin Chim Acta, 1984, 136(2/3): 219-228. DOI:10.1016/0009-8981(84)90295-x |

| [22] | Geisen U, Benk C, Beyersdorf F, et al. Neuron-specific enolase correlates to laboratory markers of haemolysis in patients on long-term circulatory support[J]. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg, 2015, 48(3): 416-420. DOI:10.1093/ejcts/ezu513 |

| [23] | Johnsson P, Blomquist S, Lührs C, et al. Neuron-specific enolase increases in plasma during and immediately after extracorporeal circulation[J]. Ann Thorac Surg, 2000, 69(3): 750-754. DOI:10.1016/s0003-4975(99)01393-4 |

| [24] | Haertel F, Babst J, Bruening C, et al. Effect of hemolysis regarding the characterization and prognostic relevance of neuron specific enolase (NSE) after cardiopulmonary resuscitation with extracorporeal circulation (eCPR)[J]. J Clin Med, 2023, 12(8): 3015. DOI:10.3390/jcm12083015 |

2025, Vol. 34

2025, Vol. 34