2. 首都医科大学附属北京世纪坛医院急诊科,北京 100038

2. Department of Emergency Medicine, Beijing Shijitan Hospital, Capital Medical University, Beijing 100038, China

老年社区获得性肺炎(community-acquired pneumonia, CAP)是指≥65岁以上人群发生的肺炎,是老年人感染性疾病死亡的最大原因[1-2]。大约10%的CAP患者发生重症社区获得性肺炎(severe community-acquired pneumonia, SCAP)需入住重症医学科(intensive care unit, ICU),病死率高达25%~50%[3-4]。老年人因高龄、基础疾病多、营养状态差等原因SCAP的发生率及病死率更高,且多数老年SCAP患者就诊急诊。因此,老年SCAP的管理是老年急危重症的重要组成部分。胸部计算机断层扫描(computed tomography, CT)是SCAP患者诊断和(或)治疗效果评估的常规检查方式。近年来,通过胸CT获取的第十二胸椎水平竖脊肌横截面积(cross sectional area of erector spinalis muscle, ESMcsa)被证实与成人SCAP患者不良结局密切相关[5-7]。但是目前国内关于住院期间竖脊肌的动态变化、急性肌肉消耗与不良健康结局相关性的研究有限。本研究旨在探索急性肌肉消耗与老年SCAP患者28 d死亡的关系,为从肌肉角度改善患者预后提供依据。

1 资料与方法 1.1 研究对象本研究为前瞻性队列研究,连续收集2022年1月1日至2022年10月31日就诊北京朝阳医院急诊抢救室的老年患者。研究期间,新型冠状病毒(novel Coronavirus Disease 2019,COVID-19)阳性患者转入指定医院,本研究仅收录阴性患者。入选标准:(1)年龄≥65岁;(2)符合2019年美国感染病学会(Infectious Diseases Society of America,IDSA)/美国胸科学会(American Thoracic Society,ATS)(简称2019 IDSA/ATS)制定的重症肺炎诊断标准[8]。排除标准:(1)入院24 h内和(或)第14天无胸部CT或其他临床资料不完整者;(2)既往周围神经肌肉疾病史或存在急性周围神经肌肉疾病;(3)近3个月内外伤、手术史,既往胸椎手术史;(4)影像图像质量不满意(如有人工制品、解剖结构异常);(5)严重免疫抑制状态的患者。

本研究经北京朝阳医院伦理委员会批准(审批号:2022-ke-430),并在中国临床试验注册中心注册(注册号:ChiCTR230007037)。所有受试者自愿参加研究并签署临床研究知情同意书。

1.2 资料收集收集患者的一般人口学特征:年龄、性别、体重指数(body mass index, BMI)、吸烟史、饮酒史;基础疾病史包括高血压、糖尿病、冠心病、慢性阻塞性肺疾病、慢性肝病、脑卒中等并计算合并症指数(Charlson comorbidity index, CCI)。记录入院后首次血常规、生化、电解质、凝血功能、血气分析结果。24 h内进行量表评估包括临床衰弱量表(clinical frailty scale, CFS)、急性生理与慢性健康评估Ⅱ(acute physiology and chronic health evaluation Ⅱ, APACHE Ⅱ)和CURB65评分标准。

所有入选患者入院24 h内及第14天行胸部CT扫描。采用美国GE公司64排螺旋CT,扫描范围肺尖至肺底。所有图像经PACS发送至AW Volume Share 7工作站(GE Medical Systems S.C.S),应用纵隔窗进行分析,采用工作站自带的CT直方图软件“X Section”,手动勾画感兴趣区域(region of interest, ROI),软件自动计算ROI面积。在胸12椎体下缘水平测量竖脊肌横断面面积,计算双侧总和记为ESMcsa,该操作由两名非影像科专业急诊科医生经培训后分别进行测定取平均值。

1.3 统计学方法运用SPSS 26.0软件,所有定量资料进行正态性检验,符合正态分布数据以均数±标准差(x±s)表示,组间比较采用两独立样本的t检验。非正态分布数据以中位数(四分位数)[M(Q1, Q3)]表示,采用Mann-Whitney U检验。无序分类资料以例(%)表示,采用χ2检验。组内前后ESMcsa的比较根据差值是否正态,若差值符合正态分布,采用配对样本的t检验,差值非正态采用Wilcoxon符号秩检验。采用多因素Cox回归模型分析老年重症肺炎患者28 d死亡的危险因素。采用受试者工作特征(receiver operating characteristic, ROC)曲线分析ESMcsa下降值对28 d死亡的预测价值,相对危险度用风险比(Hazard ratio, HR)和95%置信区间(confidence interval, CI)表示。计算约登指数(Youden index, YI)确定ESMcsa下降值预测90 d的病死率的最佳截断值,并分高肌肉消耗组和低肌肉消耗组。应用Log-rank法进行生存比较,绘制不同肌肉消耗状态的Kaplan–Meier生存曲线。以P < 0.05为差异有统计学意义。

2 结果 2.1 患者一般资料本研究共纳入106例急诊老年SCAP患者,根据28 d随访结果分为死亡组30例和存活组76例,患者一般临床资料见表 1。与生存组患者相比,死亡组患者年龄大,CFS评分高,前白蛋白(pre-albumin, PAB)低(均P < 0.05)。而BMI、CCI得分、吸烟饮酒比例,白细胞计数、血红蛋白、血小板、肌酐、D二聚体、降钙素原、APACHEⅡ和CURB65评分均差异无统计学意义(P > 0.05)。对两组患者入院第1天及第14天ESMcsa下降值进行比较显示,死亡组患者ESMcsa下降值[3.01 (-1.51, 7.73) cm2 vs. 0.80 (-2.58, 4.57) cm2,P=0.020]高于生存组。

| 指标 | 总人数(n=106) | 生存组(n=76) | 死亡组(n=30) | Z/χ2/t值 | P值 |

| 年龄(岁)a | 82.0(70.0, 86.0) | 78.0(69.0, 85.0) | 84.5(80.0, 89.0) | 2.827 | 0.005 |

| 男性(n, %) | 59(55.7) | 40(52.6) | 19(63.3) | 0.998 | 0.318 |

| BMI(kg/m2)a | 22.9(21.2, 25.1) | 22.9(21.1, 24.7) | 22.7(21.2, 27.7) | 0.635 | 0.525 |

| 吸烟史(n, %) | 44(41.5) | 36(47.4) | 8(26.7) | 3.797 | 0.051 |

| 饮酒史(n, %) | 41(38.7) | 32(42.1) | 9(30.0) | 1.329 | 0.249 |

| CCI(分)a | 6(5, 7) | 6(5, 7) | 6(5, 8) | 1.098 | 0.272 |

| WBC(×109/L)a | 10.1(7.9, 15.5) | 10.1(7.9, 15.3) | 10.1(7.8, 16.0) | 0.133 | 0.894 |

| HGB(g/L)a | 118(90, 132) | 121(103, 135) | 113(85, 124) | 1.603 | 0.109 |

| PLT(×109/L)a | 178(138, 239) | 177(135, 251) | 183(134, 232) | 0.382 | 0.702 |

| PCT(ng/mL)a | 0.3(0.1, 3.5) | 0.3(0.1, 4.5) | 0.5(0.1, 2.5) | 0.039 | 0.969 |

| PAB(mg/L)a | 95.0(47.5, 162.5) | 105.0(60.0, 180.0) | 60.0(20.0, 117.5) | 2.995 | 0.003 |

| 肌酐(µmol/L)a | 81.7(63.8, 136.3) | 81.3(62.8, 125.4) | 93.7(65.1, 180.5) | 1.143 | 0.253 |

| CFS(分)a | 6(5, 7) | 6(5, 7) | 7(6, 7) | 2.372 | 0.018 |

| APACHEⅡ(分)a | 17(13, 22) | 17(13, 22) | 19(16, 23) | 1.830 | 0.067 |

| CURB65(分)a | 3(2, 3) | 3(2, 3) | 3(2, 3) | 0.568 | 0.570 |

| ESMcsa下降值(cm2)a | 1.99(-2.25, 4.85) | 0.80(-2.58, 4.57) | 3.01(-1.51, 7.73) | 2.329 | 0.020 |

| 注:BMI为体质量指数,CCI为合并症指数,WBC为白细胞计数,HGB为血红蛋白,PLT为血小板计数,PCT为降钙素原,PAB为前白蛋白,CFS为临床衰弱量表,APACHEⅡ为急性生理学与慢性健康评估Ⅱ,ESMcsa为竖脊肌横截面积;a为M (Q1, Q3) | |||||

对生存组和死亡组患者的第1天和第14天ESMcsa分别进行组间比较。入院第1天:死亡组患者ESMcsa低于生存组[(22.75±5.55) cm2 vs. (26.81±6.87) cm2,P=0.005];第14天:死亡组ESMcsa低于生存组[20.94 (15.31, 24.01) cm2 vs. 25.52 (20.49, 30.92) cm2,P < 0.001],提示死亡组患者ESMcsa在基线及住院第14天均低于生存组。分别对两组患者第1天和第14天ESMcsa进行组内比较,结果显示生存组患者在入院第1天和14 d ESMcsa无明显动态变化(P=0.286),死亡组在入院第14天ESMcsa低于入院第1天(P < 0.001),提示死亡组患者ESMcsa可能存在急性消耗,见表 2。

| 总人数(n=106) | 生存组(n=76) | 死亡组(n=30) | t/Z值 | P值 | |

| 第1天ESMcsa(cm2)a | 25.67±6.75 | 26.81±6.87 | 22.75±5.55 | 2.886 | 0.005 |

| 第14天ESMcsa(cm2)b | 23.67(19.49, 27.66) | 25.52(20.49, 30.92) | 20.94(15.31, 24.01) | 3.847 | < 0.001 |

| Z值 | 2.796 | 1.067 | 3.301 | ||

| P值 | 0.005 | 0.286 | < 0.001 | ||

| 注:a为x±s,b为M(Q1, Q3) | |||||

以是否发生28 d死亡为因变量,将单因素分析中差异有统计学意义的指标(年龄、PAB、CFS和ESMcsa下降值)纳入多因素Cox回归方程进行分析。校正混杂因素后,ESMcsa下降值仍是老年SCAP患者28 d死亡的独立危险因素(HR=1.116, 95%CI: 1.029~1.210,P=0.008),见表 3。

| 变量 | B | SE | Wald | P | HR | 95%CI |

| 年龄 | 0.051 | 0.020 | 6.364 | 0.012 | 1.052 | 1.011~1.094 |

| PAB | -0.010 | 0.004 | 8.024 | 0.005 | 0.990 | 0.983~0.997 |

| ESMcsa下降值 | 0.110 | 0.041 | 7.060 | 0.008 | 1.116 | 1.029~1.210 |

| 注:PAB为前白蛋白,ESMcsa为竖脊肌横截面积 | ||||||

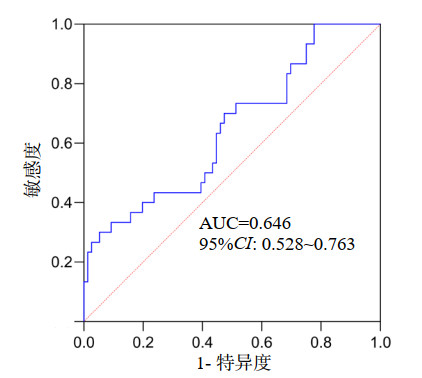

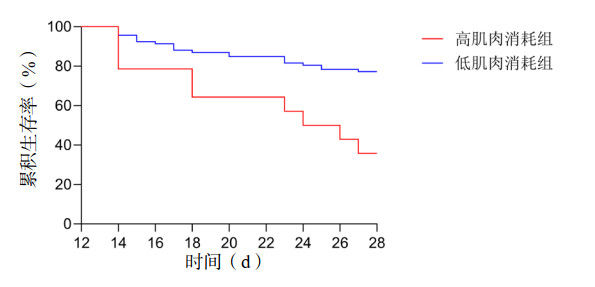

ESMcsa下降值预测老年SCAP患者28 d死亡AUC为0.646(95%CI: 0.528~0.763,P=0.020),见图 1。以最大YI为界,ESMcsa下降值预测老年SCAP患者28 d死亡的最佳截断值为6.22 cm2,敏感度为30.0%,特异度为94.74%。按照最佳截断值将ESMcsa下降值分为高肌肉消耗组和低肌肉消耗组,高肌肉消耗组28 d死亡风险高于低肌肉消耗组(Log-rank χ2=11.412,P=0.001),如图 2。

|

| 图 1 ESMcsa下降值预测老年SCAP患者28 d死亡的ROC曲线 Fig 1 ROC curve of ESMcsa loss for predicting 28-day mortality in older patients with SCAP |

|

|

|

| 图 2 急性肌肉消耗状态与老年SCAP患者28 d死亡的Kaplan–Meier曲线 Fig 2 Kaplan Meier curve of acute muscle wasting status and 28-day mortality in older patients with SCAP |

|

|

2018年,Welch等[9]首次提出急性肌少症的概念,这是因急性炎症负担和肌肉废用导致肌肉的急性丧失。随后,欧洲老年人肌肉减少症工作组也重新确定了急性和慢性肌肉减少症的亚类别[10]。然而,有些患者住院期间肌肉质量和功能发生了显著变化,但不符合肌少症的标准,不能称之为急性肌少症,这种情况可以称为急性肌肉减少,文献中也有的称为急性肌肉消耗性疾病。急性肌肉消耗与住院时间延长、康复费用增加以及出院时需要机构护理或社会护理等卫生经济成本增加有关。此外,危重患者的急性肌肉损失可能是机械通气延迟脱机的主要原因,也是院内病死率和发病率增加的预测因素[11]。因此,急性肌肉消耗是一个非常重要但在急诊领域研究较少的问题,目前有关住院期间胸部影像数据的动态变化、急性肌肉消耗与不良健康结局相关性的研究有限。本研究通过观察老年SCAP的治疗过程中胸部CT来源的竖脊肌的动态变化,证实急性肌肉消耗可预测老年重症肺炎患者28 d死亡。

2013年,Puthucheary等[12]报道称,急性肌肉消耗在危重症患者中发生的早且迅速,股直肌横截面积在入院第一周下降10.3%,在入院前10 d下降17.7%。该研究奠定了急性肌肉消耗的基础。随后,Parry等[13]报道在入院的前10 d内,股直肌、中间股直肌和股四头肌的厚度迅速减少。Pardo等[14]研究发现在重症监护室护理的第一周,危重症患者的股四头肌厚度的下降超过了16%,3周内下降24%,由此可见入院早期肌肉减少的速度更快。Hadda等[15]研究证明超声测量的肌肉变化更早、更大与住院病死率、机械通气持续时间和重症监护病房获得性衰弱(Intensive care unit-aquired weakness, ICU-AW)相关。脓毒症或急性呼吸衰竭患者的早期肌肉改变与出院时躯体功能相关,在ICU提供康复治疗可能对患者的短期和长期结局产生积极影响,增强肌肉力量可缩短机械通气时间和改善生活质量[16]。

近些年来,随着影像技术的发展,CT成为肌肉研究中广泛使用的成像方式,通过CT来评估急性肌肉消耗的研究也越来越多。Yuan等[17]对ICU机械通气患者的一项研究表明急性ESMcsa减少提示存在肌肉萎缩和骨骼肌功能减退,可预测ICU-AW并与患者60 d病死率有密切关系。该研究表示在机械通气患者中使用竖脊肌而不是其他骨骼肌,如胸大肌、股四头肌和腰大肌,是因为ESMcsa可以在不考虑上肢和下肢位置或姿势的情况下进行测量,并且可以在胸部CT时确定。一项纵向研究通过对胸部CT衍生的胸肌面积的系列测量,发现急性呼吸系统恶化与骨骼肌横截面积的加速丧失有关[18]。Gil等[19]研究显示可预测COVID-19幸存者的长期疲劳、肌痛和医疗费用。在一项由95例急性COVID-19住院患者和两次时间不同的CT扫描组成的特征明确的队列研究中[20],急性肌肉减少症(通过胸肌和ESM的标准化降低来确定)与较差的临床结果相关。这些数据为评估动态肌肉损失作为临床结果的预测指标以及针对急性肌肉减少症改善COVID-19患者的临床结果奠定了基础。然而,一项针对脓毒症患者L3水平肌肉的动态观察随访发现,急性肌肉质量损失与3个月时生活质量和身体功能下降有关,与1年病死率无关[21]。考虑不同的研究结果矛盾的原因可能受到入选人群异质性、选择偏差和不同的CT间隔的影响。

本研究创新点是选取了CT间隔时间为14 d的患者,消除了CT间隔对肌肉消耗的影响,在不增加辐射及成本的前提下对胸部CT的资料进行二次分析,得出急性肌肉消耗是老年重症肺炎患者28 d死亡的独立危险因素。本文存在一定局限性:(1)本研究为单中心研究,样本量小,部分危重症患者可能无法完成胸部CT的复查,因此可能存在选择偏倚。(2)本研究中胸部影像数据的分析并不全面,未纳入胸部肌间脂肪组织、肌内脂肪组织。未来,需要进一步开展大样本多中心的研究证实该结论。

综上所述,住院期间的急性肌肉消耗可预测老年SCAP患者28 d死亡,为从肌肉角度改善患者预后提供了依据。

利益冲突 所有作者声明无利益冲突

作者贡献声明 商娜:负责实验设计、采集数据、分析数据、文章撰写;李秋敬:参与数据采集及分析;腾飞、张向群:统计分析指导、材料支持、支持性贡献;郭树彬:对文章进行修改审阅、行政支持和指导

| [1] | Sun YX, Li H, Pei ZC, et al. Incidence of community-acquired pneumonia in urban China: a national population-based study[J]. Vaccine, 2020, 38(52): 8362-8370. DOI:10.1016/j.vaccine.2020.11.004 |

| [2] | Han XD, Zhou F, Li H, et al. Effects of age, comorbidity and adherence to current antimicrobial guidelines on mortality in hospitalized elderly patients with community-acquired pneumonia[J]. BMC Infect Dis, 2018, 18(1): 192. DOI:10.1186/s12879-018-3098-5 |

| [3] | Nair GB, Niederman MS. Updates on community acquired pneumonia management in the ICU[J]. Pharmacol Ther, 2021, 217: 107663. DOI:10.1016/j.pharmthera.2020.107663 |

| [4] | Torres A, Chalmers JD, Dela Cruz CS, et al. Challenges in severe community-acquired pneumonia: a point-of-view review[J]. Intensive Care Med, 2019, 45(2): 159-171. DOI:10.1007/s00134-019-05519-y |

| [5] | Guo K, Cai WM, Chen YX, et al. Skeletal muscle depletion predicts death in severe community-acquired pneumonia patients entering ICU[J]. Heart Lung, 2022, 52: 71-75. DOI:10.1016/j.hrtlng.2021.11.013 |

| [6] | Yoshikawa H, Komiya K, Yamamoto T, et al. Quantitative assessment of erector spinae muscles and prognosis in elderly patients with pneumonia[J]. Sci Rep, 2021, 11(1): 4319. DOI:10.1038/s41598-021-83995-3 |

| [7] | Sun LN, Ma HF, Du GH, et al. Low skeletal muscle area at the T12 paravertebral level as a prognostic marker for community-acquired pneumonia[J]. Acad Radiol, 2022, 29(10): e205-e210. DOI:10.1016/j.acra.2021.12.026 |

| [8] | Metlay JP, Waterer GW, Long AC, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of adults with community-acquired pneumonia. an official clinical practice guideline of the American thoracic society and infectious diseases society of America[J]. Am J Respir Crit Care Med, 2019, 200(7): e45-e67. DOI:10.1164/rccm.201908-1581ST |

| [9] | Welch C, K Hassan-Smith Z, A Greig C, et al. Acute sarcopenia secondary to hospitalisation - an emerging condition affecting older adults[J]. Aging Dis, 2018, 9(1): 151-164. DOI:10.14336/AD.2017.0315 |

| [10] | Cruz-Jentoft AJ, Bahat G, Bauer J, et al. Sarcopenia: revised European consensus on definition and diagnosis[J]. Age Ageing, 2019, 48(4): 601. DOI:10.1093/ageing/afz046 |

| [11] | Ali NA, O'Brien JM Jr, Hoffmann SP, et al. Acquired weakness, handgrip strength, and mortality in critically ill patients[J]. Am J Respir Crit Care Med, 2008, 178(3): 261-268. DOI:10.1164/rccm.200712-1829OC |

| [12] | Puthucheary ZA, Rawal J, McPhail M, et al. Acute skeletal muscle wasting in critical illness[J]. JAMA, 2013, 310(15): 1591-1600. DOI:10.1001/jama.2013.278481 |

| [13] | Parry SM, El-Ansary D, Cartwright MS, et al. Ultrasonography in the intensive care setting can be used to detect changes in the quality and quantity of muscle and is related to muscle strength and function[J]. J Crit Care, 2015, 30(5): 1151.e9-1151.14. DOI:10.1016/j.jcrc.2015.05.024 |

| [14] | Pardo E, El Behi H, Boizeau P, et al. Reliability of ultrasound measurements of quadriceps muscle thickness in critically ill patients[J]. BMC Anesthesiol, 2018, 18(1): 205. DOI:10.1186/s12871-018-0647-9 |

| [15] | Hadda V, Kumar R, Khilnani GC, et al. Trends of loss of peripheral muscle thickness on ultrasonography and its relationship with outcomes among patients with sepsis[J]. J Intensive Care, 2018, 6(1): 81. DOI:10.1186/s40560-018-0350-4 |

| [16] | Mayer KP, Thompson Bastin ML, Montgomery-Yates AA, et al. Acute skeletal muscle wasting and dysfunction predict physical disability at hospital discharge in patients with critical illness[J]. Crit Care, 2020, 24(1): 637. DOI:10.1186/s13054-020-03355-x |

| [17] | Yuan G, Zhang J, Mou ZF, et al. Acute reduction of erector spinae muscle cross-sectional area is associated with ICU-AW and worse prognosis in patients with mechanical ventilation in the ICU: a prospective observational study[J]. Medicine, 2021, 100(47): e27806. DOI:10.1097/MD.0000000000027806 |

| [18] | Mason SE, Moreta-Martinez R, Labaki WW, et al. Respiratory exacerbations are associated with muscle loss in current and former smokers[J]. Thorax, 2021, 76(6): 554-560. DOI:10.1136/thoraxjnl-2020-215999 |

| [19] | Gil S, de Oliveira Júnior GN, Sarti FM, et al. Acute muscle mass loss predicts long-term fatigue, myalgia, and health care costs in COVID-19 survivors[J]. J Am Med Dir Assoc, 2023, 24(1): 10-16. DOI:10.1016/j.jamda.2022.11.013 |

| [20] | Attaway A, Welch N, Dasarathy D, et al. Acute skeletal muscle loss in SARS-CoV-2 infection contributes to poor clinical outcomes in COVID-19 patients[J]. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle, 2022, 13(5): 2436-2446. DOI:10.1002/jcsm.13052 |

| [21] | Cox MC, Booth M, Ghita G, et al. The impact of sarcopenia and acute muscle mass loss on long-term outcomes in critically ill patients with intra-abdominal sepsis[J]. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle, 2021, 12(5): 1203-1213. DOI:10.1002/jcsm.12752 |

2025, Vol. 34

2025, Vol. 34