2. 青岛市市立医院急诊科,青岛 266032;

3. 山东中医药大学附属医院急诊科,济南 250011

2. Department of Emergency, Qingdao Municipal Hospital, Qingdao 266032, China;

3. Department of Emergency, Affiliated Hospital of Shandong University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Jinan 250011, China

急性心肌梗死(acute myocardial infarction, AMI)是冠心病最严重的一种类型,对全球健康产生了重大影响[1]。虽随着医疗水平不断提高,其预后已有明显改善,但AMI患者病死率仍然很高[2],即使院内病死率,仍然在4%~5%左右[3-4]。而在早期并发恶性室性心律失常(MVA)是AMI患者发生院内死亡的主要原因[5-7],占其早期死亡人数的51%~78%[8-9]。但目前关于AMI并发MVA的危险因素尚无统一定论,且临床上缺乏有效实用的风险预测模型。因此,本研究目的是借助大样本人群队列分析出危险因素,形成可靠的临床证据,利用这些危险因素构建出可应用于临床实践的风险预测模型并进行验证,实现对AMI患者的早期分层、早期干预,以降低MVA的并发率及AMI患者的病死率。

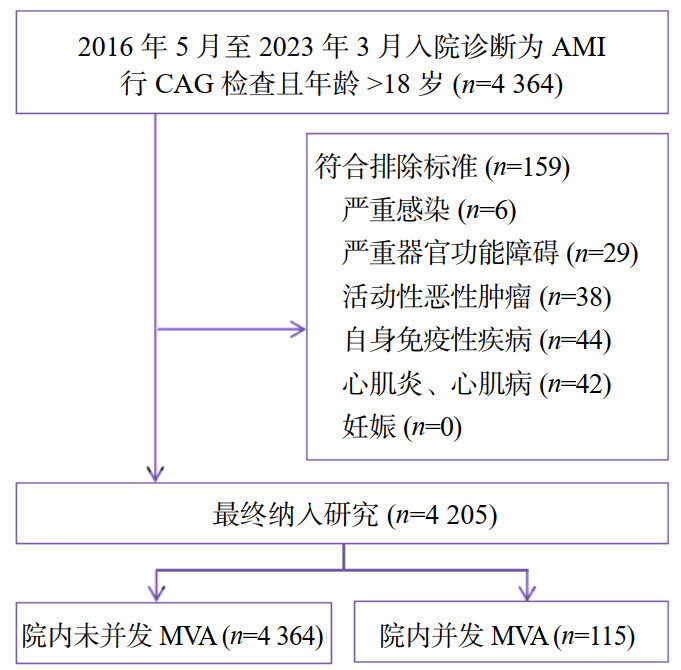

1 资料与方法 1.1 研究对象本研究为单中心回顾性队列研究,选取山东大学齐鲁医院2016年5月至2023年3月入院诊断为AMI行冠状动脉造影术(coronary angiography, CAG)检查的患者。纳入标准:①符合第三版及第四版心肌梗死通用定义中的标准;②行CAG检查;③年龄≥18岁。排除标准:①严重感染;②严重器官功能障碍;③活动性恶性肿瘤;④自身免疫性疾病;⑤心肌炎、心肌病;⑥妊娠。详细流程图如图 1所示。MVA被定义为室颤、应用电复律或静脉应用抗心律失常药物进行终止的室速。本研究通山东大学齐鲁医院伦理委员会审批(批号:KYLL-202411-060),伦理委员会同意免除签署知情同意书。

|

| 注:AMI为急性心肌梗死,CAG为冠状动脉造影术,MVA为恶性室性心律失常 图 1 研究队列人群的筛选流程 Fig 1 Flowchart of the selection process for the study cohort |

|

|

通过专病库导出一般临床资料及首份检验指标:年龄、性别、共病(有无高血压、糖尿病、冠心病)、心肌梗死病史、个人史(是否吸烟、饮酒)、收缩压、舒张压、呼吸频率、心率、体重指数;中性粒细胞计数、红细胞平均宽度、单核细胞计数、淋巴细胞计数、血小板计数、白蛋白、肌酐、尿素氮、高密度脂蛋白胆固醇、低密度脂蛋白胆固醇、血糖、血钾、血镁、同型半胱氨酸、胱抑素C、D-二聚体、肌酸激酶同工酶、高敏肌钙蛋白Ⅰ、NT-proBNP。通过电子病例系统,收集心电图指标:AMI类型(有无ST段抬高)、有无J波出现;收集CAG结果:左主干(LM)、左前降支(LAD)、左回旋支、右冠状动脉是否狭窄≥50%,是否存在双支病变(以上血管中存在任意2条狭窄≥50%,但不包括LM),是否存在≥3支病变(以上血管中存在任意≥3条狭窄≥50%,或≥50%的血管中包含LM)。

1.3 统计学方法借助R软件(版本4.4.1,2024-06-14,https://www.r-project.org/)进行统计分析。对连续变量进行D'Agostino正态性检验,若符合正态分布,以均数±标准差(x±s)表示,两组间Student's t检验评估;若不符合正态分布,以中位数和四分位数[M(Q1, Q3)]表示,两组间Mann-Whitney U检验。对分类变量,以频数(%)表示,两组间χ2检验或Fisher精确概率法比较。采用二元logistic回归进行AMI并发MVA的单因素分析,借助逐步回归法筛选构建最佳预测模型的变量并进行多因素分析。绘制列线图将模型可视化。绘制ROC曲线以评价模型的预测性能。采用Bootstrap自抽样(B=1000)法进行内部验证。绘制校准曲线以评估模型预测概率与实际概率的一致性。绘制决策曲线以评估模型临床获益度。计算VIF评价各变量有无多重共线性。以P < 0.05为差异有统计学意义。

2 结果 2.1 队列人群的基线特征该队列共纳入4 205例入院诊断为AMI的患者,其中有115例在院期间并发MVA,占比2.735%。有无并发MVA的基线特征比较见表 1。与未并发MVA人群相比,并发MVA人群年龄更大、男性占比更低、BMI更低、心率更快、收缩压及舒张压均较低、呼吸频率更快,血糖、单核细胞计数、红细胞平均宽度、肌酐、尿素氮、同型半胱氨酸、胱抑素C、D-二聚体、肌酸激酶同工酶、高敏肌钙蛋白Ⅰ、NT-proBNP、中性粒细胞计数/淋巴细胞计数、LM及LAD狭窄≥50%的比例、≥3支血管狭窄≥50%的比例、STEMI及J波出现的比例、Killip分级为Ⅱ级或Ⅲ级或Ⅳ级的比例均较高,而血钾及白蛋白较低(以上所有P均 < 0.05)。

| 指标 | 非MVA (n=4090) | MVA (n=115) | t/χ2/Z值 | P值 |

| 年龄(岁)a | 62.00 (53.00, 69.00) | 66.00 (59.00, 76.00) | -5.185 | < 0.001 |

| 男性b | 3 132 (76.6) | 74 (64.3) | 8.573 | 0.003 |

| BMI (kg/m2)a | 25.59 (23.51, 27.73) | 24.73 (22.94, 26.78) | 2.450 | 0.014 |

| 心率(次/min)a | 73.00 (65.00, 82.00) | 81.00 (69.50, 91.00) | -4.734 | < 0.001 |

| 收缩压(mmHg)a | 128.00 (115.00, 142.00) | 123.00 (108.50, 134.00) | 3.549 | < 0.001 |

| 舒张压(mmHg)a | 75.00 (67.00, 84.00) | 71.00 (61.50, 82.00) | 3.108 | 0.002 |

| 呼吸频率(次/min)a | 18.00 (17.00, 19.00) | 18.00 (17.00, 20.00) | -4.198 | < 0.001 |

| 共病b | ||||

| 高血压 | 2517 (61.5) | 75 (65.2) | 0.494 | 0.482 |

| 冠心病 | 3991 (97.6) | 114 (99.1) | 0.444d | |

| 糖尿病 | 1395 (34.1) | 45 (39.1) | 1.040 | 0.308 |

| 既往心梗b | 256 (6.3) | 11 (9.6) | 1.538 | 0.215 |

| 吸烟b | 2240 (54.8) | 62 (53.9) | 0.008 | 0.931 |

| 饮酒b | 2083 (50.9) | 56 (48.7) | 0.143 | 0.705 |

| 血液学指标 | ||||

| 血糖(mmol/L)a | 5.45 (4.80, 7.00) | 7.74 (5.32, 12.10) | -7.055 | < 0.001 |

| 单核细胞(×109/L)a | 0.47 (0.37, 0.62) | 0.58 (0.44, 0.78) | -4.978 | < 0.001 |

| 红细胞分布宽度(%)a | 12.70 (12.30, 13.10) | 12.90 (12.50, 13.50) | -4.129 | < 0.001 |

| 血小板(×109/L)a | 224.00 (186.25, 266.00) | 220.00 (188.00, 263.00) | -0.098 | 0.922 |

| 白蛋白(g/L)a | 40.60 (37.80, 43.30) | 37.20 (34.40, 40.75) | 7.133 | < 0.001 |

| 肌酐(μmol/L)a | 74.00 (64.00, 85.00) | 82.00 (68.00, 101.00) | -3.939 | < 0.001 |

| 尿素氮(mmol/L)a | 4.90 (4.00, 6.05) | 6.99 (4.64, 9.65) | -6.032 | < 0.001 |

| 同型半胱氨酸(umol/L)a | 14.30 (11.50, 18.10) | 15.90 (11.80, 19.95) | -2.233 | 0.026 |

| 胱抑素C(mg/L)a | 0.93 (0.80, 1.09) | 1.04 (0.86, 1.27) | -4.066 | < 0.001 |

| HDL-C (mmol/L)a | 1.00 (0.86, 1.16) | 1.03 (0.87, 1.17) | -1.054 | 0.292 |

| LDL-C (mmol/L)a | 2.42 (1.91, 3.00) | 2.44 (1.96, 3.10) | -0.342 | 0.733 |

| 血钾(mmol/L)a | 4.12 (3.88, 4.37) | 3.90 (3.60, 4.32) | 4.723 | < 0.001 |

| 血镁(mmol/L)a | 0.89 (0.84, 0.94) | 0.88 (0.83, 0.94) | 0.928 | 0.353 |

| D-二聚体(μg/mL)a | 0.13 (0.08, 0.26) | 0.29 (0.16, 0.66) | -8.421 | < 0.001 |

| 肌酸激酶同工酶(ng/mL)a | 2.20 (1.30, 8.90) | 6.60 (2.35, 85.50) | -6.444 | < 0.001 |

| log10 (hs-cTnI)(ng/L)c | 2.69 (1.24) | 3.25 (1.26) | -18.317 | < 0.001 |

| log10 (NT-proBNP)(pg/mL)a | 2.86 (2.45, 3.24) | 3.41 (2.91, 3.77) | -8.472 | < 0.001 |

| NLR a | 2.92 (2.15, 4.24) | 5.16 (2.97, 8.32) | -7.349 | < 0.001 |

| AMI类型b | 45.748 | < 0.001 | ||

| STEMI | 1 706 (41.7) | 83 (72.2) | ||

| NSTEMI | 1 565 (38.3) | 14 (12.2) | ||

| 未分类 | 819 (20.0) | 18 (15.7) | ||

| J波b | 606 (14.8) | 32 (27.8) | 13.716 | < 0.001 |

| 冠状动脉狭窄≥50%b | ||||

| LM | 428 (10.5) | 20 (17.4) | 4.934 | 0.026 |

| LAD | 3 482 (85.1) | 106 (92.2) | 3.883 | 0.049 |

| LCX | 2 540 (62.1) | 75 (65.2) | 0.339 | 0.561 |

| RCA | 2 688 (65.7) | 84 (73.0) | 2.354 | 0.125 |

| 2支血管 | 1 142 (27.9) | 24 (20.9) | 2.435 | 0.119 |

| ≥3支血管 | 1 890 (46.2) | 68 (59.1) | 6.994 | 0.008 |

| Killip分级b | < 0.001d | |||

| Ⅰ级 | 3 216 (78.6) | 53 (46.1) | ||

| Ⅱ级 | 613 (15.0) | 22 (19.1) | ||

| Ⅲ级 | 177 (4.3) | 12 (10.4) | ||

| Ⅳ级 | 84 (2.1) | 28 (24.3) | ||

| 注:a为M(Q1, Q3),b为(例, %),c为x±s,d为Fisher精确概率法;BMI为体重指数,HDL-C为高密度脂蛋白胆固醇,LDL-C为低密度脂蛋白胆固醇,hs-cTnI为高敏肌钙蛋白Ⅰ,NT-proBNP为N末端B型利钠肽前体,NLR为中性粒细胞计数/淋巴细胞计数,AMI为急性心肌梗死,STEMI为ST段抬高型心肌梗死,NSTEMI为非ST段抬高型心肌梗死,LM为左主干,LAD为左前降支,LCX为左回旋支,RCA为右冠状动脉,MVA为恶性室性心律失常;1 mmHg=0.133 kPa | ||||

单因素Logistic回归分析显示,年龄、男性、BMI、心率、收缩压、舒张压、呼吸频率、血糖、单核细胞计数、红细胞平均宽度、白蛋白、肌酐、尿素氮、胱抑素C、血钾、D-二聚体、肌酸激酶同工酶、高敏肌钙蛋白Ⅰ、NT-proBNP、中性粒细胞计数/淋巴细胞计数、心肌梗死类型、J波出现、LM及LAD狭窄≥50%、≥3支血管狭窄≥50%、Killip分级均与MVA发生相关。采用双向逐步Logistic回归法筛选出可构建最佳预测模型的变量,分别为年龄(X1)、舒张压(X2)、呼吸频率(X3)、血糖(X4)、血钾(X5)、对数化的NT-proBNP(X6)、心肌梗死类型(NSTEMI=X7, 未分类=X8)、J波(X9)、Killip分级(Ⅱ=X10, Ⅲ=X11, Ⅳ=X12),将以上变量纳入多因素Logistic回归分析,得出回归方程为ln(p/1-p)=-4.699+0.029×X1-0.012×X2+0.059×X3+0.148×X4-1.175×X5+0.866×X6-1.427×X7-0.475×X8+0.758×X9+0.294×X10+0.902×X11+1.815×X12。回归分析结果见表 2。

| 因素 | 单因素logistic回归 | 多因素logistic回归, 截距=-4.699 | |||||

| OR | 95%CI | P值 | β | OR | 95%CI | P值 | |

| 年龄 | 1.050 | (1.032, 1.069) | < 0.001 | 0.029 | 1.03 | (1.010, 1.051) | 0.004 |

| 男性 | 0.552 | (0.376, 0.821) | 0.003 | – | – | – | – |

| BMI | 0.938 | (0.887, 0.992) | 0.026 | – | – | – | – |

| 心率 | 1.033 | (1.021, 1.043) | < 0.001 | – | – | – | – |

| 收缩压 | 0.982 | (0.972, 0.992) | < 0.001 | – | – | – | – |

| 舒张压 | 0.975 | (0.960, 0.990) | 0.001 | -0.012 | 0.988 | (0.972, 1.004) | 0.131 |

| 呼吸频率 | 1.195 | (1.115, 1.275) | < 0.001 | 0.059 | 1.061 | (0.984, 1.140) | 0.117 |

| 血糖 | 1.237 | (1.184, 1.292) | < 0.001 | 0.148 | 1.159 | (1.102, 1.218) | < 0.001 |

| 单核细胞计数 | 6.025 | (3.367, 10.503) | < 0.001 | – | – | – | – |

| 红细胞分布宽度 | 1.208 | (1.071, 1.340) | 0.001 | – | – | – | – |

| 白蛋白 | 0.860 | (0.827, 0.895) | < 0.001 | – | – | – | – |

| 肌酐 | 1.006 | (1.003, 1.009) | < 0.001 | – | – | – | – |

| 尿素氮 | 1.163 | (1.112, 1.212) | < 0.001 | – | – | – | – |

| 胱抑素C | 2.106 | (1.487, 2.988) | < 0.001 | – | – | – | – |

| 血钾 | 0.266 | (0.167, 0.423) | < 0.001 | -1.175 | 0.309 | (0.196, 0.482) | < 0.001 |

| D-二聚体 | 1.102 | (1.031, 1.164) | 0.001 | – | – | – | – |

| 肌酸激酶同工酶 | 1.003 | (1.002, 1.005) | < 0.001 | – | – | – | – |

| log10(hs-cTnI) | 1.459 | (1.248, 1.714) | < 0.001 | – | – | – | – |

| log10(NT-proBNP) | 4.948 | (3.539, 6.969) | < 0.001 | 0.866 | 2.378 | (1.598, 3.570) | < 0.001 |

| NLR | 1.117 | (1.085, 1.152) | < 0.001 | – | – | – | – |

| AMI类型 | |||||||

| STEMI | Reference | Reference | |||||

| NSTEMI | 0.184 | (0.100, 0.315) | < 0.001 | -1.427 | 0.24 | (0.126, 0.426) | < 0.001 |

| 未分类 | 0.452 | (0.261, 0.739) | 0.003 | -0.475 | 0.622 | (0.348, 1.057) | 0.091 |

| J波 | 2.217 | (1.442, 3.328) | < 0.001 | 0.758 | 2.135 | (1.339, 3.335) | 0.001 |

| LM | 1.800 | (1.072, 2.884) | 0.019 | – | – | – | – |

| LAD | 2.056 | (1.096, 4.393) | 0.039 | – | – | – | – |

| ≥3支血管 | 1.684 | (1.159, 2.468) | 0.007 | – | – | – | – |

| Killip分级 | |||||||

| Ⅰ级 | Reference | Reference | |||||

| Ⅱ级 | 2.177 | (1.290, 3.557) | 0.003 | 0.294 | 1.341 | (0.763, 2.284) | 0.292 |

| Ⅲ级 | 4.112 | (2.064, 7.579) | < 0.001 | 0.902 | 2.463 | (1.183, 4.777) | 0.011 |

| Ⅳ级 | 20.227 | (12.075, 33.373) | < 0.001 | 1.815 | 6.138 | (3.289, 11.245) | < 0.001 |

| 注:BMI为体重指数,hs-cTnI为高敏肌钙蛋白Ⅰ,NT-proBNP为N末端B型利钠肽前体,NLR为中性粒细胞计数/淋巴细胞计数,AMI为急性心肌梗死,STEMI为ST段抬高型心肌梗死,NSTEMI为非ST段抬高型心肌梗死,LM为左主干,LAD为左前降支,MVA为恶性室性心律失常,–表示无相关数据 | |||||||

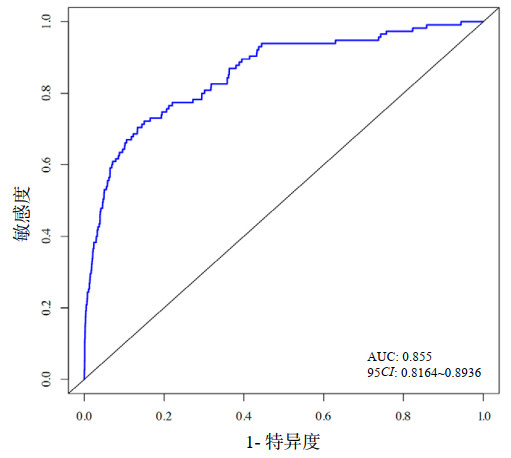

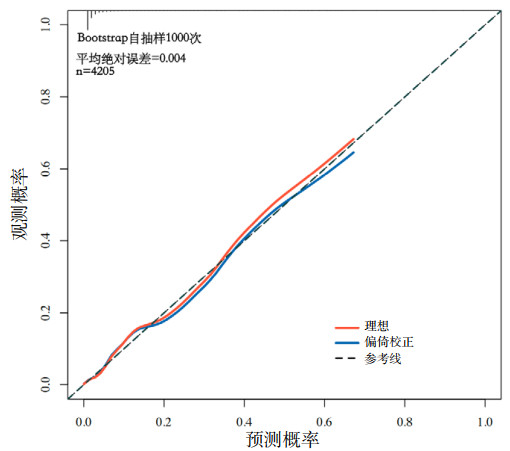

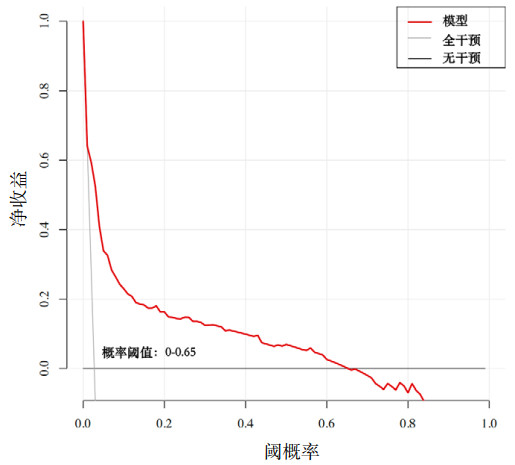

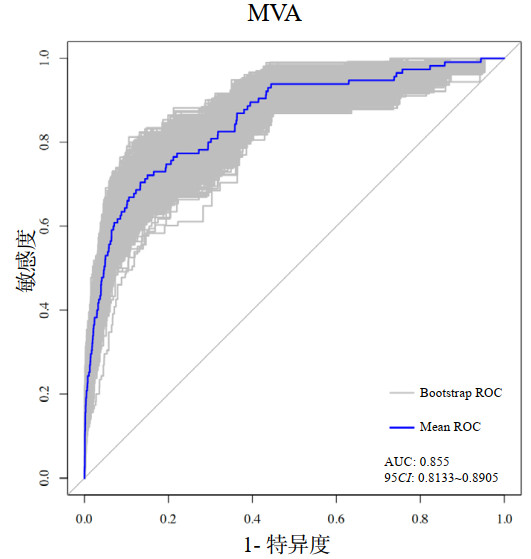

该模型ROC曲线(图 2)的曲线下面积(AUC)为0.855(95%CI: 0.816~0.894),表明该模型具有较好的预测性能。Hosmer-Lemeshow检验(χ2=14.178,P=0.077)及校准曲线(图 3)均显示其预测概率与实际概率具有较好的一致性。决策曲线(图 4)显示该模型在概率阈值为0%~65%时具有较好的临床净获益。

|

| 图 2 AMI并发MVA风险预测模型的ROC曲线 Fig 2 ROC curve of the risk prediction model for AMI complicated with MVA |

|

|

|

| 图 3 AMI并发MVA风险预测模型的校准曲线 Fig 3 Calibration curve of the risk prediction model for AMI complicated with MVA |

|

|

|

| 图 4 AMI并发MVA风险预测模型的决策曲线 Fig 4 Decision curve of the risk prediction model for AMI complicated with MVA |

|

|

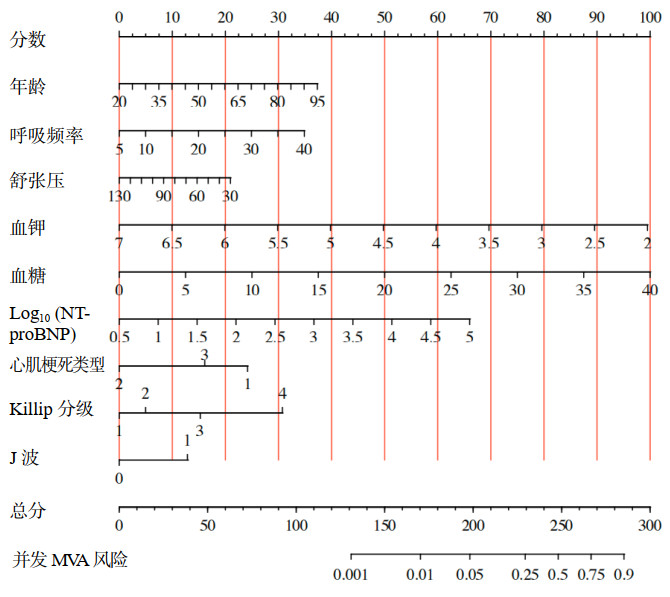

对年龄、舒张压、呼吸频率、血糖、血钾、对数化的NT-proBNP、心肌梗死类型、J波、Killip分级9个变量构建出的预测模型绘制列线图(图 5),根据每个变量的数值或类型对应points轴上的分数,计算出总分,根据总分得出并发MVA的风险。采用Bootstrap自助重抽样法(n=1 000次)进行内部验证(图 6),说明该模型具有良好的判别性能(AUC: 0.855, 95%CI: 0.813~0.891)。

|

| 图 5 AMI并发MVA风险预测的列线图模型 Fig 5 Nomogram model for risk prediction of AMI complicated with MVA |

|

|

|

| 图 6 Bootstrap自助重抽样法(n=1 000次)内部验证ROC曲线 Fig 6 Internal validation of ROC curve using Bootstrap resampling method (n=1 000) |

|

|

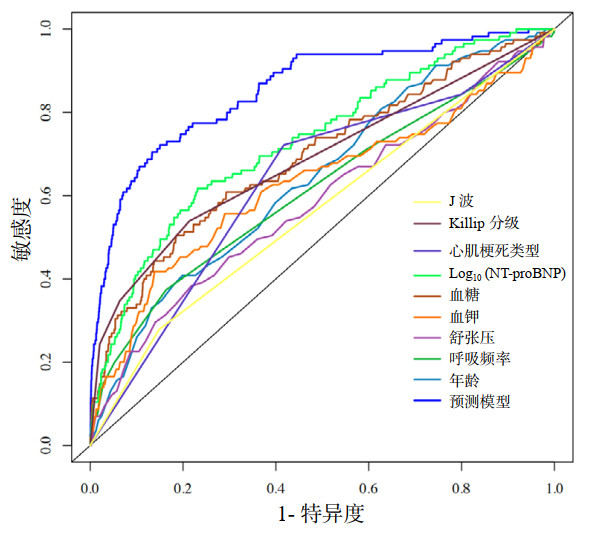

9个变量联合应用显示出最高的AUC(AUC: 0.855, 95%CI: 0.816~0.894),表示该预测模型较任何单一因子预测性能更强(均P < 0.001)(图 7):年龄(AUC: 0.642, 95%CI: 0.591~0.693)、舒张压(AUC: 0.585, 95%CI: 0.527~0.643)、呼吸频率(AUC: 0.615, 95%CI: 0.556~0.673)、血糖(AUC: 0.693, 95%CI: 0.638~0.747)、血钾(AUC: 0.629, 95%CI: 0.568~0.690)、对数化的NT-proBNP(AUC: 0.731, 95%CI: 0.682~0.781)、心肌梗死类型(AUC: 0.635, 95%CI: 0.586~0.684)、J波(AUC: 0.565, 95%CI: 0.524~0.607)、Killip分级(AUC: 0.687, 95%CI: 0.636~0.738)。

|

| 图 7 预测模型及各单一预测因子ROC曲线(预测性能)的比较 Fig 7 Comparison of ROC curves for the prediction model and individual predictors (predictive performance) |

|

|

纳入模型各变量的广义方差膨胀因子(GVIF)及调整自由度(Df)后的GVIF[GVIF(1/(2df))]均接近于1(表 3),表明纳入模型的各变量间无多重共线性。

| 变量 | 年龄 | 呼吸频率 | 舒张压 | 血钾 | 血糖 | log10(NT-proBNP) | AMI类型 | Killip分级 | J波 |

| GVIF | 1.204 | 1.047 | 1.057 | 1.013 | 1.069 | 1.290 | 1.093 | 1.152 | 1.005 |

| Df | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 |

| GVIF[1/(2df)] | 1.097 | 1.023 | 1.028 | 1.007 | 1.034 | 1.136 | 1.023 | 1.024 | 1.002 |

| 注:GVIF为广义方差膨胀因子,NT-proBNP为N末端B型利钠肽前体,AMI为急性心肌梗死 | |||||||||

本研究中,MVA的并发率为2.73%,与既往研究结果相近[10-11],分析得出对模型贡献度最大的三个因素为血液学指标。血钾降低可通过心肌细胞自律性改变、动作电位时程延长、传导速度降低、有效不应期缩短及动态底物变化等多种机制诱发MVA[12-13],低钾血症易并发MVA已成为近年来公认的医学事实[14-15]。血糖升高致使AMI患者易并发MVA亦提出了多种机制,高血糖可能与胰岛素抵抗和儿茶酚胺过量产生有关,导致脂肪分解和游离脂肪酸的释放[16],从而引起心肌细胞膜损伤和钙超载[17];另外高血糖可致QT间期延长和离散[18],还与较大的梗死面积、较差的左心室功能[19-20]及血清炎症生物标志物的增加[20-21]等相关,以上均可能促使MVA发生。NT-proBNP作为反应心肌应激状态的生物标志物,其升高与心功能下降及预后密切相关[22-23]。类似的研究中亦指出,作为与NT-proBNP有同一来源且分裂比例相同的BNP[24],是AMI患者并发MVA的独立危险因素[25-26]。

心电指标中,ST段抬高和J波出现时更易并发MVA。STEMI相对于NSTEMI通常意味着冠状动脉阻塞更完全、心肌坏死的范围更大及程度更重,从而更易并发MVA。从机制上来讲,有部分研究认为ST段抬高程度代表了动作电位第2相再入的潜在弥散梯度,这是导致早期后除极的主要因素[27],而早期后除极为发生MVA的潜在机制[28]。目前,J波促使MVA发生的机制未明,主要有早期复极或晚期去极两种学说[29],有待进一步明确机制,以早期药物干预,阻断J波产生从而避免MVA发生。

年龄较大被普遍认为是影响AMI患者预后的重要因素之一[30-31],衰老会降低心脏对应激的耐受性、增加对缺血的易感性[30-32],随着年龄的增长,心脏储备功能及舒张功能都逐渐减弱[33-34],在心功能较差的基础上更易并发MVA[35-37],既往研究[38]与本研究均支持这一结论。呼吸频率作为反应病情严重程度的生命体征之一,在一项前瞻性队列研究中显示,呼吸频率越快,AMI患者预后越差[39]。呼吸频率增快可视为交感神经过度激活的表观指征,而交感神经过度激活是AMI并发MVA的重要机制[40]。

Killip分级反映AMI后有无心力衰竭及血流动力学改变严重程度,其等级较高、心功能较差时,心电活动极不稳定[41],促使MVA的发生[42]。同时,血流动力学不稳定最直观的表现即为血压下降,在动脉顺应性逐渐降低的中老年人群中,DBP或许比SBP表现更敏感[43],而冠脉血液灌注相对更依赖于DBP,从而形成心肌缺血并发MVA的恶性循环。

最后,本研究有一定的局限性。第一,构建预测模型的候选变量为依据临床经验及既往研究结论选取,但这或许并不能包含所有真正的危险因素,更有意义的指标有待挖掘;第二,本研究未根据AMI发生至并发MVA的时间分层探讨,有待扩大样本量进行分层分析,识别出不同时间段内并发MVA的危险因素并构建预测模型,从而更有针对性的早期干预;第三,本研究为单中心回顾性队列研究,未进行外部验证,有待进行前瞻性、多中心队列研究,进一步验证本研究结果。

综上所述,AMI并发MVA的预测因素有:年龄较大、呼吸频率较快、血糖及NT-proBNP水平较高、血钾及舒张压水平较低、ST段抬高、J波出现、Killip分级较高,均为临床常规指标,构建出的预测模型经评价和验证具有良好性能,可借助列线图简单、准确地进行风险评估后对AMI患者有针对性的早期干预。因此,本研究对降低MVA的并发率及AMI患者的病死率具有较高的临床价值。

利益冲突 所有作者声明无利益冲突

作者贡献声明 宋东丽:选题,设计研究、实施研究、统计分析、论文撰写;刘胜囡:设计研究指导;吴硕:统计分析指导;高洁、张晓、崔维凯、王怡帆:数据采集;王甲莉:研究指导、论文修改、经费支持;陈玉国:研究指导、论文修改

| [1] | Reed GW, Rossi JE, Cannon CP. Acute myocardial infarction[J]. Lancet, 2017, 389(10065): 197-210. DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30677-8 |

| [2] | Wang YK, Tang JN, Shen YL, et al. Prognostic utility of soluble TREM-1 in predicting mortality and cardiovascular events in patients with acute myocardial infarction[J]. J Am Heart Assoc, 2018, 7(12): e008985. DOI:10.1161/JAHA.118.008985 |

| [3] | Margaritis M, Sanna F, Lazaros G, et al. Predictive value of telomere length on outcome following acute myocardial infarction: evidence for contrasting effects of vascular vs. blood oxidative stress[J]. Eur Heart J, 2017, 38(41): 3094-3104. DOI:10.1093/eurheartj/ehx177 |

| [4] | Long Z, Liu W, Zhao ZP, et al. Case fatality rate of patients with acute myocardial infarction in 253 chest pain centers - China, 2019-2020[J]. China CDC Wkly, 2022, 4(24): 518-521. DOI:10.46234/ccdcw2022.026 |

| [5] | Priori SG, Blomström-Lundqvist C, Mazzanti A, et al. 2015 ESC Guidelines for the management of patients with ventricular arrhythmias and the prevention of sudden cardiac death: The Task Force for the Management of Patients with Ventricular Arrhythmias and the Prevention of Sudden Cardiac Death of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Endorsed by: Association for European Paediatric and Congenital Cardiology (AEPC)[J]. Eur Heart J, 2015, 36(41): 2793-2867. DOI:10.1093/eurheartj/ehv316. |

| [6] | Szymanski C, Bel A, Cohen I, et al. Comprehensive annular and subvalvular repair of chronic ischemic mitral regurgitation improves long-term results with the least ventricular remodeling[J]. Circulation, 2012, 126(23): 2720-2727. DOI:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.033472 |

| [7] | Fei YD, Wang Q, Hou JW, et al. Macrophages facilitate post myocardial infarction arrhythmias: roles of gap junction and KCa3.1[J]. Theranostics, 2019, 9(22): 6396-6411. DOI:10.7150/thno.34801 |

| [8] | Masuda M, Nakatani D, Hikoso S, et al. Clinical impact of ventricular tachycardia and/or fibrillation during the acute phase of acute myocardial infarction on in-hospital and 5-year mortality rates in the percutaneous coronary intervention era[J]. Circ J, 2016, 80(7): 1539-1547. DOI:10.1253/circj.CJ-16-0183 |

| [9] | Kurmi P, Patidar A, Patidar S, et al. Incidence and prognostic significance of arrhythmia in acute myocardial infarction presentation: an observational study[J]. Cureus, 2024, 16(10): e71564. DOI:10.7759/cureus.71564 |

| [10] | Garcia R, Marijon E, Karam N, et al. Ventricular fibrillation in acute myocardial infarction: 20-year trends in the FAST-MI study[J]. Eur Heart J, 2022, 43(47): 4887-4896. DOI:10.1093/eurheartj/ehac579 |

| [11] | Xu X, Wang Z, Yang JG, et al. Burden of cardiac arrhythmias in patients with acute myocardial infarction and their impact on hospitalization outcomes: insights from China acute myocardial infarction (CAMI) registry[J]. BMC Cardiovasc Disord, 2024, 24(1): 218. DOI:10.1186/s12872-024-03889-w |

| [12] | Tazmini K, Frisk M, Lewalle A, et al. Hypokalemia promotes arrhythmia by distinct mechanisms in atrial and ventricular myocytes[J]. Circ Res, 2020, 126(7): 889-906. DOI:10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.119.315641 |

| [13] | Tse G, Li KHC, Cheung CKY, et al. Arrhythmogenic mechanisms in hypokalaemia: insights from pre-clinical models[J]. Front Cardiovasc Med, 2021, 8: 620539. DOI:10.3389/fcvm.2021.620539 |

| [14] | Ahmed A, Zannad F, Love TE, et al. A propensity-matched study of the association of low serum potassium levels and mortality in chronic heart failure[J]. Eur Heart J, 2007, 28(11): 1334-1343. DOI:10.1093/eurheartj/ehm091 |

| [15] | Colombo MG, Kirchberger I, Amann U, et al. Association of serum potassium concentration with mortality and ventricular arrhythmias in patients with acute myocardial infarction: a systematic review and meta-analysis[J]. Eur J Prev Cardiol, 2018, 25(6): 576-595. DOI:10.1177/2047487318759694 |

| [16] | Paolisso P, Foà A, Bergamaschi L, et al. Impact of admission hyperglycemia on short and long-term prognosis in acute myocardial infarction: MINOCA versus MIOCA[J]. Cardiovasc Diabetol, 2021, 20(1): 192. DOI:10.1186/s12933-021-01384-6 |

| [17] | Martínez MS, García A, Luzardo E, et al. Correction: energetic metabolism in cardiomyocytes: molecular basis of heart ischemia and arrhythmogenesis[J]. Vessel Plus, 2018, 2(10): 32. DOI:10.20517/2574-1209.2017.34 |

| [18] | Marfella R, Rossi F, Giugliano D. QTc dispersion, hyperglycemia, and hyperinsulinemia[J]. Circulation, 1999, 100(25): e149. DOI:10.1161/01.cir.100.25.e149 |

| [19] | Capes SE, Hunt D, Malmberg K, et al. Stress hyperglycaemia and increased risk of death after myocardial infarction in patients with and without diabetes: a systematic overview[J]. Lancet, 2000, 355(9206): 773-778. DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(99)08415-9 |

| [20] | Marfella R, Siniscalchi M, Esposito K, et al. Effects of stress hyperglycemia on acute myocardial infarction: role of inflammatory immune process in functional cardiac outcome[J]. Diabetes Care, 2003, 26(11): 3129-3135. DOI:10.2337/diacare.26.11.3129 |

| [21] | Deedwania P, Kosiborod M, Barrett E, et al. Hyperglycemia and acute coronary syndrome: a scientific statement from the American heart association diabetes committee of the council on nutrition, physical activity, and metabolism[J]. Circulation, 2008, 117(12): 1610-1619. DOI:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.188629 |

| [22] | McKie PM, Burnett JC Jr. NT-proBNP: the gold standard biomarker in heart failure[J]. J Am Coll Cardiol, 2016, 68(22): 2437-2439. DOI:10.1016/j.jacc.2016.10.001 |

| [23] | Sakamoto D, Sotomi Y, Matsuoka Y, et al. Prognostic utility and cutoff differences in NT-proBNP levels across subgroups in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: insights from the PURSUIT-HFpEF registry[J]. J Card Fail, 2024: S1071-9164(24)00925-4. DOI: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2024.10.440. |

| [24] | Weber M, Hamm C. Role of B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP) and NT-proBNP in clinical routine[J]. Heart, 2006, 92(6): 843-849. DOI:10.1136/hrt.2005.071233 |

| [25] | Blangy H, Sadoul N, Dousset B, et al. Serum BNP, hs-C-reactive protein, procollagen to assess the risk of ventricular tachycardia in ICD recipients after myocardial infarction[J]. Europace, 2007, 9(9): 724-729. DOI:10.1093/europace/eum102 |

| [26] | 陈继兴, 陈世雄, 唐庆业, 等. Gal-3、hs-CRP及BNP在急性心肌梗死并发恶性室性心律失常患者中的应用价值[J]. 海军医学杂志, 2023, 44(5): 501-505. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1009-0754.2023.05.017 |

| [27] | Wang XP, Wei LF, Wu Y, et al. ST-segment elevation predicts the occurrence of malignant ventricular arrhythmia events in patients with acute ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction[J]. BMC Cardiovasc Disord, 2023, 23(1): 61. DOI:10.1186/s12872-023-03099-w |

| [28] | Di Diego JM, Antzelevitch C. Cellular basis for ST-segment changes observed during ischemia[J]. J Electrocardiol, 2003, 36(Suppl): 1-5. DOI:10.1016/j.jelectrocard.2003.09.001 |

| [29] | Zhang LY, Dong SJ, Zhao WB, et al. Relationship between an ischaemic J wave pattern and ventricular fibrillation in ST-elevation myocardial infarction patients[J]. Int J Gen Med, 2021, 14: 8725-8735. DOI:10.2147/IJGM.S337638 |

| [30] | Dong M, Yang ZY, Fang HC, et al. Aging attenuates cardiac contractility and affects therapeutic consequences for myocardial infarction[J]. Aging Dis, 2020, 11(2): 365-376. DOI:10.14336/AD.2019.0522 |

| [31] | Dhalla NS, Rangi S, Babick AP, et al. Cardiac remodeling and subcellular defects in heart failure due to myocardial infarction and aging[J]. Heart Fail Rev, 2012, 17(4/5): 671-681. DOI:10.1007/s10741-011-9278-7 |

| [32] | Preston CC, Oberlin AS, Holmuhamedov EL, et al. Aging-induced alterations in gene transcripts and functional activity of mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation complexes in the heart[J]. Mech Ageing Dev, 2008, 129(6): 304-312. DOI:10.1016/j.mad.2008.02.010 |

| [33] | Yang XP, Sreejayan N, Ren J. Views from within and beyond: narratives of cardiac contractile dysfunction under senescence[J]. Endocrine, 2005, 26(2): 127-137. DOI:10.1385/ENDO:26:2:127 |

| [34] | Gates PE, Tanaka H, Graves J, et al. Left ventricular structure and diastolic function with human ageing. Relation to habitual exercise and arterial stiffness[J]. Eur Heart J, 2003, 24(24): 2213-2220. DOI:10.1016/j.ehj.2003.09.026 |

| [35] | Guo T, Fan YZ, Chen M, et al. Cardiovascular implications of fatal outcomes of patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19)[J]. JAMA Cardiol, 2020, 5(7): 811-818. DOI:10.1001/jamacardio.2020.1017 |

| [36] | Kwon Y, Koene RJ, Kwon O, et al. Effect of sleep-disordered breathing on appropriate implantable cardioverter-defibrillator therapy in patients with heart failure: a systematic review and meta-analysis[J]. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol, 2017, 10(2): e004609. DOI:10.1161/CIRCEP.116.004609 |

| [37] | Park S, Nguyen NB, Pezhouman A, et al. Cardiac fibrosis: potential therapeutic targets[J]. Transl Res, 2019, 209: 121-137. DOI:10.1016/j.trsl.2019.03.001 |

| [38] | 朱小刚, 韩凌, 赵燕, 等. BNP、LVEF和年龄对非ST段抬高性急性冠脉综合征患者院内恶性室性心律失常的预测价值[J]. 临床和实验医学杂志, 2016, 15(20): 2007-2010. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1671-4695.2016.20.014 |

| [39] | Barthel P, Wensel R, Bauer A, et al. Respiratory rate predicts outcome after acute myocardial infarction: a prospective cohort study[J]. Eur Heart J, 2013, 34(22): 1644-1650. DOI:10.1093/eurheartj/ehs420 |

| [40] | Wang Y, Hu HS, Yin J, et al. TLR4 participates in sympathetic hyperactivity Post-MI in the PVN by regulating NF-κB pathway and ROS production[J]. Redox Biol, 2019, 24: 101186. DOI:10.1016/j.redox.2019.101186 |

| [41] | Kobayashi Y, Tanno K, Ueno A, et al. In-hospital electrical storm in acute myocardial infarction - clinical background and mechanism of the electrical instability[J]. Circ J, 2018, 83(1): 91-100. DOI:10.1253/circj.CJ-18-0785 |

| [42] | Piers SRD, Everaerts K, van der Geest RJ, et al. Myocardial scar predicts monomorphic ventricular tachycardia but not polymorphic ventricular tachycardia or ventricular fibrillation in nonischemic dilated cardiomyopathy[J]. Heart Rhythm, 2015, 12(10): 2106-2114. DOI:10.1016/j.hrthm.2015.05.026 |

| [43] | Bahat G, Ribeiro H, Sheppard JP, et al. Twelve hot questions in the management of hypertension in patients aged 80+ years and their answers with the help of the 2023 European Society of Hypertension Guidelines[J]. J Hypertens, 2024, 42(11): 1837-1847. DOI:10.1097/HJH.0000000000003844 |

2025, Vol. 34

2025, Vol. 34