意识评估(consciousness assessment)是神经重症医生临床诊疗活动的主要内容,但由于神经重症患者的特殊状态,准确评价患者意识存在一定难度。临床意识障碍(disorder of consciousness,DOC)评估经历了以下几个发展的阶段。

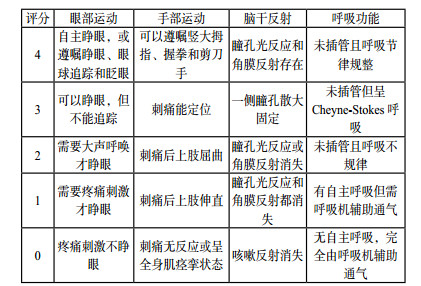

1 量表评估DOC评估最常用的方法就是评分量表,通常包括评价指标(变量)、评分标准和评分数值三个部分。通过分值计算得出分数,从而进行量化评价。评价指标的选择应遵循简易、方便、直接、常规、实用、可重复的原则。诞生于1974年的格拉斯哥评分(Glasgow Coma Scale,GCS)是评估昏迷和意识障碍患者应用最广泛的评估手段[1-4],并成为多种临床评分的重要组成部分,例如APACH Ⅱ评分、SOFA评分、WFNS评分等。但随着临床实践的不断深入和积累,GCS评分也暴露了一些缺陷,如缺乏脑干功能的评估;忽略了瞳孔变化的观察在神经重症患者诊疗中的重要意义;特殊人群(儿童、老年痴呆患者、闭锁综合症患者等)的不适用性[5-6]。因此,一些学者在GCS评分的基础上进行了修正和补充,演变出Glasgow-Pittsberg评分[7]、Adelaide儿科昏迷评分(Adelaide Pediatric Coma Scale,APCS) [8]、格拉斯哥-列日评分(Glasgow-Liège Scale,GLCS)[9]、FOUR(Full Outline of UnResponsiveness)评分(图 1)[10]、西方神经感官刺激(Western Neuro Sensory Stimulation Profile,WNSSP)[11]、因斯布鲁克昏迷量表(Innsbruck Coma Scale,ICS)[12]等。

|

| 图 1 全面无反应性量表评分细则 |

|

|

2005年美国Wijdicks和同事们提出的全面无反应性量表—FOUR评分,曾被誉为“新时代的格拉斯哥评分”。研究证实,相对于GCS评分,FOUR评分能提供更多的神经系统细节,更准确、更适合于神经重症患者的临床评估[13-15]。

遗憾的是,无论何种量表,在评估神经重症患者的意识中都存在着较高的误诊率,尤其是在评估植物状态(vegetative state,VS)、无反应觉醒综合症、微意识状态(minimally conscious state,MCS)等情况[16-18]。这是因为传统评分的量表大多是基于行为或者观察,即通过反复的检查来判定患者对于多种刺激是否具有可重复的、定向的、自主的行为能力,但是有些意识的细微征象很难通过肉眼来观察,或是检测者执行的准确性,判断标准等原因,导致了传统量表在临床意识评估上的缺陷。同时,医学的发展,尤其是影像学的发展,对既往界定的意识下限不断提出新的思考[19]。

2 客观评价方法意识最初的概念是自我与环境之间的完全感知状态,包括觉醒和觉知[20]。觉醒是通过检测患者能否睁开眼睛来判断。但需要强调的是某些意识状态的存在,例如微意识状态(MCS),患者虽能睁眼,但仍存在意识障碍。觉知是指脑对任何一种刺激的感知和反应能力,临床往往是根据患者的行为能否遵循指令或对刺激的响应程度来判定[21],但缺乏精确而有效的方法。很多学者发现,仅基于患者的行为很难准确评估患者意识水平[22-23]。因此,探讨不基于行为的、客观的技术来评估意识障碍,判断患者临床预后是现实的要求。近年来,神经影像技术和脑电图是临床研究最为广泛的两个领域。

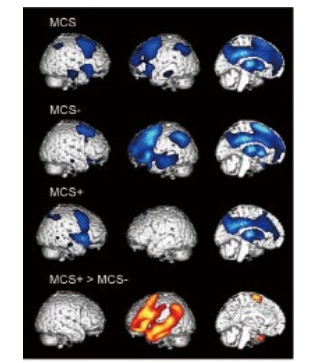

2.1 神经影像 2.1.1 正电子发射型计算机断层显像(positron emission computed tomography,PET)PET是最早应用于意识障碍临床研究的影像技术之一[24-25]。其实质是分子生物学与医学影像学的相互交叉融合,运用标记后的葡萄糖来反映局部脑组织功能。临床研究表明,觉知的损伤和一些特定脑区葡萄糖的摄取量降低有关,如一些联络皮质[26]、两侧丘脑等[27]。利用PET技术,还可以进一步区分一些意识障碍的亚型。如MCS临床可以细分为“MCS+”与“MCS-”,前者的意识水平稍好,可以理解一些语言,并能完成简单的指令动作。PET的对比研究发现,与MCS-患者相比,MCS+患者在语言理解的相关脑区还保留一定的代谢活性[28](图 2)。

|

| 图 2 PET下MCS-患者与MCS+患者图像 |

|

|

与PET相比,fMRI的空间和实践分辨率更高,而且没有电离辐射,它提供了无创、可重复的大脑活化图谱。Moritz等[29]首次报道了利用fMRI预测昏迷患者的脑功能。研究表明,人脑中存在多个脑功能的网络。fMRI证实,DOC患者网络内部功能连接是受损的,且受损程度与患者意识障碍的程度相关[30]。fMRI的缺陷是患者必须保持不动,需要复杂的后处理技术,同时对于一些安装心脏起搏器或体内有金属植入物的患者都有限制。

2.1.3 其他方法除此之外,一些特殊序列和磁共振成像方法为临床评估意识提供了有益帮助,如弥散加权成像(diffusion weighted imaging, DWI)、弥散张量成像(diffusion tensor imaging, DTI)和各向异性系数(fractional anisotropy,FA)等。

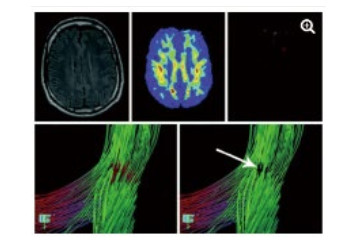

DWI利用梯度回旋技术来监测水分子弥散的难易程度,能比其他影像手段更早发现脑缺血。DTI是DWI的发展和深化, 结合FA等参数能独特显示全脑白质传导束,并且能够评估其功能的完整性。研究表明,重度脑外伤患者胼胝体膝部和压部的FA值下降,同时压部白质纤维束数量减少。这些变化不仅仅与GCS评分有关,还和患者的预后,包括认知评分显著相关[31-34]。借助DTI技术,能从形态学上解释意识障碍存在的结构基础,直观评价患者损伤程度[34](图 3)及预后[35],具有较高的精准性。在心搏骤停后昏迷患者意识评估研究中发现,DTI及FA的联合应用在预测患者预后不良的灵敏度达94%,特异度达100%[35]。

|

| 图 3 一例49岁TBI患者,常规MRI检查未发现明显异常(左上图)运用FA技术显示在左侧额叶白质中发现一个FA减少的区域(上中图),运用DTI显示局部纤维提示不联系(箭头所指) |

|

|

DOC患者应用脑电进行意识评估是指研究人员应用各种刺激后记录刺激所产生的脑电频率或频率的变化,通过了解脑干网状觉醒系统和支持丘脑皮层回路的皮层结构的互动,来评估患者意识变化。常用的方法包括脑电反应、短时诱发电位、节律改变以及经颅磁刺激术(transcranial magnetic stimulation, TMS)[36]等。

3 未来发展方向意识评估是当代神经科学领域最具有挑战性的领域之一。错误评估一方面可能引发伦理问题,另一方面还可能因为缺乏肯定的判断给医疗保健卫生预算造成巨大负担[37-38]。得益于神经影像、计算机技术的发展,神经重症患者意识评估手段不断丰富。fMRI的出现让意识第一次被赋予了“形态学”的特质,但是仍不够精确。Fisher和Appelbaum[39]指出“应用神经影像技术作为法律的一部分来衡量意识”可能会导致一些法律案件的混乱。

3.1 扰动复杂性指数(perturbational complexity index,PCI)PCI指数被认为是近年来对于意识评估研究的一个重要成果。它采用TMS直接对皮层实施一个微刺激,然后在EEG上记录到刺激后的反应信号,通过复杂的数学分析,得到的指数称为PCI。其实质是反映大脑对于信息与整合的能力[40]。PCI的测量可以区分正常觉醒、睡眠、全身麻醉以及DOC的不同亚组(闭锁综合症、微意识状态、无觉醒反应综合征)(图 4)[40]。PCI为神经重症医生提供了一个在无意识到有意识图谱上可重复的度量方法,而不再依靠有或无的方式去认识意识障碍。

|

| 图 4 PCI的测量可以区分DOC患者不同的亚组 |

|

|

PCI指数的出现则意味着意识的“量化”在将来会成为一种可能实现精确评估意识的方向。当然这种量化方式与早期量表评估时经验性设定的数值不可同日而语。因为它还涉及到了神经影像和复杂的计算机技术。

3.2 更微观的模式也有学者从微观的角度去阐述意识障碍的原因。由心搏骤停、窒息或溺水以及创伤等导致的缺血缺氧脑损伤后,常常会引起全脑缺血缺氧的改变,但患者常出现不同的转归,如持续植物状态(PVS),微意识状态(MCS),意识恢复以及脑死亡等。有研究认为是和不同脑组织对于缺血缺氧的抵抗程度不同有关,皮层、海马、纹状体等较易受到损害,下丘脑和脑干损害较轻,导致患者处于昏迷或不同的意识状态中。通过动物的实验模拟及组织切片,目前认为这种差异的存在与Na+/K+ ATP酶分子亚型的不同分布相关。如何尽可能详细地阐述这种机制对于理解不同意识障碍的产生,并由此寻找治疗的靶点去干预,可能会是将来研究的一个热点。

目前DOC存在的机制,尤其是患者对信息的接受、整合、响应的过程及其调控机制,仍有待于进一步的深入研究。如何更精确地判断意识,预测预后仍将是神经重症医生需要不断探索的研究内容。计算机技术的介入,大数据时代的福利,我们相信,神经重症医生对于DOC患者的意识评估会更加细化,亚组的区分以及相互之间的鉴别手段针对性会更强,对于患者的预后判断也更加精准。

| [1] | Teasdale G, Jennett B. Assessment of coma and impaired consciousness. A practical scale[J]. Lancet, 1974, 2(7872): 81-84. DOI:10.1016/s0140-6736(74)91639-0 |

| [2] | Teasdale G, Jennett B. Assessment and prognosis of coma after head injury[J]. Acta Neurochir (Wien), 1976, 34(1-4): 45-55. DOI:10.1007/bf01405862 |

| [3] | Middleton PM. Practical use of the Glasgow Coma Scale: a comprehensive narrative review of GCS methodology[J]. Australas Emerg Nurs J, 2012, 15(3): 170-183. DOI:10.1016/j.aenj.2012.06.002 |

| [4] | Rush C. The history of the glasgow coma scale: an interview with professor Bryan Jennett[J]. Int J Trauma Nurs, 1997, 3(4): 114-118. DOI:10.1016/s1075-4210(97)90005-5 |

| [5] | Kerby JD, MacLennan PA, Burton JN, et al. Agreement between prehospital and emergency department glasgow coma scores[J]. J Trauma, 2007, 63(5): 1026-1031. DOI:10.1097/TA.0b013e318157d9e8 |

| [6] | Bledsoe BE, Casey MJ, Feldman J, et al. Glasgow Coma Scale Scoring is often inaccurate[J]. Prehosp Disaster Med, 2015, 30(1): 46-53. DOI:10.1017/S1049023X14001289 |

| [7] | Edgren E, Hedstrand U, NordinM, et al. Prediction of outcome after cardiac arrest[J]. Crit Care Med, 1987, 15(9): 820-825. DOI:10.1097/00003246-198709000-00004 |

| [8] | Simpson D, Reilly P. Pediatric coma scale[J]. Lancet, 1982, 2(8295): 450. DOI:10.1016/s0140-6736(82)90486-x |

| [9] | Born JD, Albert A, Hans P, et al. Relative prognostic value of best motor response and brain stem reflexes in patients with severe head injury[J]. Neurosurgery, 1985, 16(5): 595-601. DOI:10.1097/00006123-198505000-00002 |

| [10] | Wijdicks EF, Bamlet WR, Maramattom BV, et al. Validation of a new coma scale: The FOUR score[J]. Ann Neurol, 2005, 58(4): 585-593. DOI:10.1002/ana.20611 |

| [11] | Ansell BJ, Keenan JE. The Western Neuro Sensory Stimulation Profile: a tool for assessing slow-to-recover head-injured patients[J]. Arch Phys Med Rehabil, 1989, 70(2): 104-108. |

| [12] | Benzer A, Mitterschiffthaler G, Marosi M, et al. Prediction of non-survival after trauma: Innsbruck Coma Scale[J]. Lancet, 1991, 338(8773): 977-978. DOI:10.1016/0140-6736(91)91840-q |

| [13] | Gorji MA, Hoseini SH, Gholipur A, et al. A comparison of the diagnostic power of the Full Outline of Unresponsiveness scale and the Glasgow coma scale in the discharge outcome prediction of patients with traumatic brain injury admitted to the intensive care unit[J]. Saudi J Anaesth, 2014, 8(2): 193-197. DOI:10.4103/1658-354X.130708 |

| [14] | Jamal A, Sankhyan N, Jayashree M, et al. Full Outline of Unresponsiveness score and the Glasgow Coma Scale in prediction of pediatric coma[J]. World J Emerg Med, 2017, 8(1): 55-60. DOI:10.5847/wjem.j.1920–8642.2017.01.010 |

| [15] | Bruno MA, Ledoux D, Lambermont B, et al. Comparison of the Full Outline of Unresponsiveness and Glasgow Liege Scale/Glasgow Coma Scale in an intensive care unit population[J]. Neurocrit Care, 2011, 15(3): 447-453. DOI:10.1007/s12028-011-9547-2 |

| [16] | Schnakers C, Vanhaudenhuyse A, Giacino J, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of the vegetative and minimally conscious state: clinical consensus versus standardized neurobehavioral assessment[J]. BMC Neurol, 2009, 9: 35. DOI:10.1186/1471-2377-9-35 |

| [17] | Bosco A, Lancioni GE, Olivetti Belardinelli M, et al. Vegetative state: efforts to curb misdiagnosis[J]. Cogn Process, 2010, 11(1): 87-90. DOI:10.1007/s10339-009-0355-y |

| [18] | Goldfine AM, Bardin JC, Noirhomme Q, et al. Reanalysis of " Bedside detection of awareness in the vegetative state: a cohort study"[J]. Lancet, 2013, 381(9863): 289-291. DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60125-7 |

| [19] | Kotchoubey B, Vogel D, Lang S, et al. What kind of consciousness is minimal?[J]. Brain Inj, 2014, 28(9): 1156-1163. DOI:10.3109/02699052.2014.920523 |

| [20] | Laureys S. The neural correlate of (un)awareness: lessons from the vegetative state[J]. Trends Cogn Sci (Regul Ed), 2005, 9(12): 556-559. DOI:10.1016/j.tics.2005.10.010 |

| [21] | Boly M, Massimini M, Garrido MI, et al. Brain connectivity in disorders of consciousness[J]. Brain Connect, 2012, 2(1): 1-10. DOI:10.1089/brain.2011.0049 |

| [22] | Monti MM, Vanhaudenhuyse A, Coleman MR, et al. Willful modulation of brain activity in disorders of consciousness[J]. N Engl J Med, 2010, 362(7): 579-589. DOI:10.1056/NEJMoa0905370 |

| [23] | Owen AM, Coleman MR, Boly M, et al. Using functional magnetic resonance imaging to detect covert awareness in the vegetative state[J]. Arch Neurol, 2007, 64(8): 1098-1102. DOI:10.1001/archneur.64.8.1098 |

| [24] | Selwyn R, Hockenbury N, Jaiswal S, et al. Mild traumatic brain injury results in depressed cerebral glucose uptake: an (18)FDG PET study[J]. J Neurotrauma, 2013, 30(23): 1943-1953. DOI:10.1089/neu.2013.2928 |

| [25] | Bodart O, Gosseries O, Wannez S, et al. Measures of metabolism and complexity in the brain of patients with disorders of consciousness[J]. J Neurotrauma, 2013, 30(23): 1943-1953. DOI:10.1089/neu.2013.2928 |

| [26] | Laureys S, Goldman S, Phillips C, et al. Impaired effective cortical connectivity in vegetative state: preliminary investigation using PET[J]. Neuroimage, 1999, 9(4): 377-382. DOI:10.1006/nimg.1998.0414 |

| [27] | Yamaki T, Suzuki K, Sudo Y, et al. Association between uncooperativeness and the glucose metabolism of patients with chronic behavioral disorders after severe traumatic brain injury: a cross-sectional retrospective study[J]. Biopsychosoc Med, 2018, 12: 6. DOI:10.1186/s13030-018-0125-0 |

| [28] | Bruno MA, Majerus S, Boly M, et al. Functional neuroanatomy underlying the clinical subcategorization of minimally conscious state patients[J]. J Neurol, 2012, 259(6): 1087-1098. DOI:10.1007/s00415-011-6303-7 |

| [29] | Moritz CH, Rowley HA, Haughton VM, et al. Functional MR imaging assessment of a non-responsive brain injured patient[J]. Magn Reson Imaging, 2001, 19(8): 1129-1132. DOI:10.1016/s0730-725x(01)00432-5 |

| [30] | Vanhaudenhuyse A, Noirhomme Q, Tshibanda LJ, et al. Default net-work connectivity reflects the level of consciousness in non-communicative brain-damaged patients[J]. Brain, 2010, 133(Pt 1): 161-171. DOI:10.1093/brain/awp313 |

| [31] | Arfanakis K, Hermann BP, Rogers BP, et al. Diffusion tensor MRI in temporal lobe epilepsy[J]. Magn Reson Imaging, 2002, 20(7): 511-519. DOI:10.1016/S0730-725X(02)00509-X |

| [32] | Rutgers DR, Fillard P, Paradot G, et al. Diffusion tensor imaging characteristics of the corpus callosum in mild, moderate, and severe traumatic brain injury[J]. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol, 2008, 29(9): 1730-1735. DOI:10.3174/ajnr.A1213 |

| [33] | Newcombe V, Chatfield D, Outtrim J, et al. Mapping traumatic axonal injury using diffusion tensor imaging: correlations with functional outcome[J]. PLoS ONE, 2011, 6(5): e19214. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0019214 |

| [34] | Rutgers DR, Toulgoat F, Cazejust J, et al. White matter abnormal-lities in mild traumatic brain injury: a diffusion tensor imaging study[J]. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol, 2008, 29(3): 514-519. DOI:10.3174/ajnr.A0856 |

| [35] | Luyt CE, Galanaud D, Perlbarg V, et al. Neuro Imaging for Coma Emergence and Recovery Consortium. Diffusion tensor imaging to predict long-term outcome after cardiac arrest: a bicentric pilot study[J]. Anesthesiology, 2012, 117(6): 1311-1321. DOI:10.1097/ALN.0b013e318275148c |

| [36] | Rounis E, Maniscalco B, Rothwell JC, et al. Theta-burst transcranial magnetic stimulation to the prefrontal cortex impairs metacognitive visual awareness[J]. Cogn Neurosci, 2010, 1(3): 165-175. DOI:10.1080/17588921003632529 |

| [37] | Ojaghihaghighi S, Vahdati SS, Mikaeilpour A, Ramouz A. Comparison of neurological clinical manifestation in patients with hemorrhagic and ischemic stroke[J]. World J Emerg Med, 2017, 8(1): 34-38. DOI:10.5847/wjem.j.1920–8642.2017.01.006 |

| [38] | Medical aspects of the persistent vegetative state (2). Multi-Society Task Force on PVS[J]. N Engl J Med, 1994, 330(22): 1572-1579. DOI:10.1056/NEJM199406023302206 |

| [39] | Fisher CE, Appelbaum PS. Diagnosing consciousness: neuroimaging, law, and the vegetative state[J]. J Law Med Ethics, 2010, 38(2): 374-385. DOI:10.1111/j.1748-720X.2010.00496.x |

| [40] | Casali AG, Gosseries O, Rosanova M, et al. A theoretically based index of consciousness independent of sensory processing and behavior[J]. Sci Transl Med, 2013, 5(198): 198ra105. DOI:10.1126/scitranslmed.3006294 |

2018, Vol. 27

2018, Vol. 27