脑出血是卒中第二常见的亚型,是常导致严重残疾或死亡的危重疾病[1-3]。脑出血占所有卒中类型中的10%~20%,发病率不断上升,每年的病死率在54%左右。发现可靠、准确的预后危险因素对于脑出血患者的预后有着重要作用,能将患者按其预期的临床结果进行分层,有助于为临床决策提供信息以及进行新的治疗试验[4]。本回顾性研究旨在了解ICU内脑出血患者短期结局的危险因素,早期对患者积极进行干预和治疗,以减少病死率。

1 资料与方法 1.1 一般资料武汉大学中南医院伦理委员会已批准该研究方案,回顾性收集武汉大学中南医院重症医学科2013年1月至2018年1月入住ICU内的脑出血患者362例,入选病例依据影像学检查诊断为脑出血的患者。排除标准:年龄小于18岁、孕妇、发病时间超过7 d、入院时间小于48 h、入院24 h内无肾功能结果、肾小球滤过率(eGFR) < 15 mL/(min·1.73 m2)、既往肾功能不全、规律透析、肾移植患者及病史资料不全的患者。最终300例患者纳入本研究。使用医院内电子信息系统以及重症监护系统,收集记录患者入院时的基本信息,入ICU时格拉斯哥评分(Glasgow coma scale,GCS)、急性生理与慢性健康评分(acute physiology and chronic health evaluation,APACHEⅡ),以及实验室相关检查。临床结局指标:AKI、连续肾脏替代治疗(continuous renal replacement therapy,CRRT)、ICU内死亡结局、院内死亡结局、ICU住院时间、总住院时间、总花费。

1.2 研究方法主要研究结局为院内死亡情况,将患者分为院内死亡组和院内存活组。对患者基线资料、入院情况及辅助检查等方面进行比较。AKI的诊断基于KDIGO指南[5]。

1.3 统计学方法对于分类变量,使用χ2检验或Fisher确切概率法,用频数和百分比表示; 对于正态分布的连续变量,采用独立样本t检验,用均数±标准差(Mean±SD)表示; 对于偏态分布的连续变量,采用U检验,用中位数(四分位数)[M(P25, P75)]表示。预测院内死亡的危险因素,采用二元Logistic回归; 院内死亡情况危险因素的比较使用ROC曲线,及Kaplan-Meier生存曲线评估患者预后。使用统计软件SPSS 20.0,MedCalc及Graphpad,以P < 0.05为差异有统计学意义。

2 结果 2.1 基线资料本单中心、回顾性研究最初记录362例患者,最终纳入300例。表 1示发生院内死亡组有96例,院内存活组有204例,ICU内脑出血患者院内死亡的发生率为32%。发生院内死亡患者年龄为60岁(50,71)岁,院内存活者年龄为58.5岁(50,64)岁,院内死亡者中男性59例(61.5%),院内存活者中男性99例(48.5%),在性别比较上,差异有统计学意义(P=0.036)。此外,院内死亡组与院内存活组中GCS评分分别为7.00分(6.00,9.00)分和9.00分(8.00,10.00)分,其APACHEⅡ评分分别为25.00分(23.00,28.00)分和22.00分(21.00,23.00)分,两者在GCS评分和APACHEⅡ评分比较,差异有统计学意义(均P < 0.01)。

| 指标 | 院内死亡组 (n=96) |

院内存活组 (n=204) |

Z值/χ2值 | P值 |

| 年龄(岁)[M(P25, P75)] | 60(50, 71) | 58.5(50, 64) | -1.308 | 0.191 |

| 男性(例,%) | 59(61.5) | 99(48.5) | 4.377 | 0.036 |

| 既往史(例,%) | ||||

| 先前卒中 | 15(15.6) | 27(13.2) | 0.310 | 0.578 |

| 高血压 | 61(63.5) | 117(57.4) | 1.036 | 0.309 |

| 糖尿病 | 9(9.4) | 14(6.9) | 0.582 | 0.446 |

| 冠心病 | 10(10.4) | 13(6.4) | 1.508 | 0.219 |

| 造影剂(例,%) | 48(50.0) | 77(37.7) | 4.034 | 0.045 |

| 收缩压(mmHg)[M(P25, P75)] | 163.00(139.25, 188.75) | 158.00(140.00, 180.00) | -1.287 | 0.198 |

| 舒张压(mmHg)[M(P25, P75)] | 92.50(78.50, 109.75) | 90.00(76.50, 102.75) | -1.231 | 0.218 |

| GCS(分)[M(P25, P75)] | 7.00(6.00, 9.00) | 9.00(8.00, 10.00) | -5.561 | < 0.01 |

| APACHEⅡ(分)[M(P25, P75)] | 25.00(23.00, 28.00) | 22.00(21.00, 23.00) | -8.773 | < 0.01 |

| 实验室检查[M(P25, P75)] | ||||

| 血钠(mmol/L) | 137.70(134.08, 141.55) | 137.30(133.53, 139.45) | -1.437 | 0.151 |

| 血钾(mmol/L) | 3.68(3.35, 3.93) | 3.66(3.35, 3.91) | -0.108 | 0.914 |

| 血糖(mmol/L) | 8.00(7.11, 9.96) | 7.65(6.41, 9.20) | -2.122 | 0.034 |

| 白细胞(×109/L) | 13.19(10.63, 18.43) | 11.22(8.78, 13.80) | -3.795 | < 0.01 |

| 中性粒细胞百分比(%) | 87.55(83.43, 91.28) | 88.35(82.85, 91.30) | -0.135 | 0.893 |

| 血小板(×109/L) | 185.50(143.50, 223.25) | 179.00(142.00, 212.25) | -0.420 | 0.674 |

| 红细胞(×1012/L) | 4.43(3.76, 4.77) | 4.30(3.86, 4.62) | -0.966 | 0.334 |

| 血红蛋白(g/L) | 132.50(119.15, 144.75) | 129.00(116.13, 139.45) | -0.171 | 0.171 |

| AKI(例,%) | 58(60.4) | 30(14.7) | 65.802 | < 0.01 |

| CRRT(例,%) | 7(7.3) | 0 | 15.230 | < 0.01 |

| ICU住院时间(d) | 5(3, 8) | 3(2, 5) | -5.468 | < 0.01 |

| 住院总时间(d) | 14.5(6, 26) | 22(15, 34) | -4.601 | < 0.01 |

| 注:1 mmHg=0.133 kPa | ||||

应用二元Logistic回归分析预测脑出血患者院内死亡结局时,在考虑到其他影响因素后,表 2结果显示更低的GCS评分(OR=0.629,95%CI:0.523~0.757,P < 0.01)、更高的APACHEⅡ评分(OR=1.590,95%CI:1.369~1.847,P < 0.01)、升高的白细胞(OR=1.082,95%CI:1.028~1.139,P=0.002)和AKI的发生(OR=6.978,95%CI:3.381~14.405,P < 0.01)是脑出血患者发生院内死亡的危险因素。

| 因素 | B值 | OR | 95%CI | P值 |

| 性别 | 0.423 | 1.527 | 0.752~3.100 | 0.242 |

| 造影剂 | 0.310 | 1.363 | 0.672~2.763 | 0.391 |

| GCS评分 | -0.463 | 0.629 | 0.523~0.757 | < 0.01 |

| APACHEⅡ评分 | 0.464 | 1.590 | 1.369~1.847 | < 0.01 |

| 血糖 | 0.040 | 1.041 | 0.946~1.146 | 0.411 |

| 白细胞 | 0.079 | 1.082 | 1.028~1.139 | 0.002 |

| AKI | 1.943 | 6.978 | 3.381~14.405 | < 0.01 |

| 常数 | -10.284 | - | - | - |

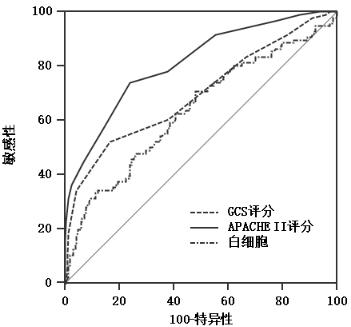

GCS评分、APACHEⅡ评分和白细胞数评估ICU内脑出血患者院内死亡的预测价值,ROC曲线分析显示,GCS评分≤7分、APACHE Ⅱ评分 > 23分、白细胞计数 > 11.26×109/L时,能较好地预测脑出血的死亡结局,其中APACHEⅡ评分的曲线下面积最大,其敏感度和特异度分别为73.96%和75.98%,见图 1,表 3。

|

| 图 1 各指标评估脑出血患者发生院内死亡的ROC曲线 Fig 1 Predictive value of ROC curve for in-hospital mortality in patients with intracerebral hemorrhage |

|

|

| 指标 | 最佳截断值 | 敏感度 (%) |

特异度 (%) |

AUC(95%CI) |

| GCS评分 | ≤7 | 52.08 | 83.33 | 0.696(0.641~0.748) |

| APAPCHEⅡ评分 | > 23 | 73.96 | 75.98 | 0.812(0.763~0.854) |

| 白细胞(×109/L) | > 11.26 | 70.83 | 51.96 | 0.636(0.579~0.690) |

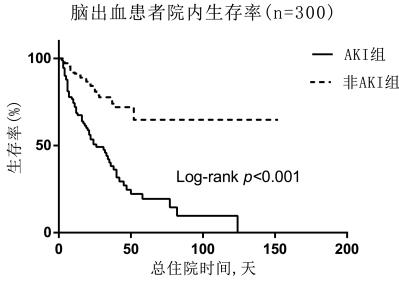

Kaplan-Meier生存曲线结果显示,非AKI患者与AKI患者相比,院内存活率更高(Log rank, χ2=41.12,P < 0.01),见图 2。

|

| 图 2 Kaplan-Meier生存曲线评估脑出血患者院内存活情况 Fig 2 Evaluation of in-hospital survival in patients with intracerebral hemorrhage by Kaplan-Meier survival curve |

|

|

脑出血属于常见的急危重疾病,常威胁人们的生命安全,需要临床工作人员早期快速诊断和治疗。一项研究表明脑出血患者的院内病死率高达30.4%[6],与本研究中院内病死率为32%的结果基本一致。此外,GCS评分作为传统的反映患者昏迷程度的评价方法,其简单、实用、省时,有利于医护人员对患者病情的协调和沟通[7]。本研究中患者的GCS评分越低,短期预后越差,与一项亚洲多中心研究[8]的结论相一致。发热、较低的GCS评分、增大的血肿范围、脑室出血和糖尿病是脑出血患者不良预后的独立预测因素。然而本研究中,既往糖尿病病史不是导致患者院内死亡的独立危险因素。

APACHEⅡ评分包括三个方面,即急性生理学评分、年龄评分及慢性健康状况评分,其中涵盖了GCS评分、患者的基础生命体征、主要的器官功能状况和生化指标的情况。在入ICU时较低的GCS评分和较高的APACHEⅡ评分表明患者严重和复杂的临床状况。APACHEⅡ评分常用于ICU内对于危重病患者预后的评估,也可以有效地评估脑出血患者的预后情况[9]。APACHEⅡ评分对于脑出血患者的预后有着重要的指导作用。在本研究中,早期识别脑出血患者中GCS评分≤7分,APACHEⅡ评分 > 23分,可预防患者疾病的进展。

此外,一些研究表明炎症标志物与脑出血的不良预后有关[6, 10-11]。本研究中,与患者的住院病死率有关,其中白细胞计数 > 11.26×109/L,是脑出血患者院内死亡的危险因素。一项前瞻性纳入ICU内脑出血患者的研究显示,单因素分析中升高的白细胞与患者30 d病死率有关,在多因素分析中白细胞对30 d病死率影响无统计学意义[12]。然而本研究中,在单因素和多因素分析中,升高的白细胞均与脑出血患者的院内病死率有关。这些研究结果进一步证明了炎症是导致继发性脑损害的关键因素之一,炎症介导的脑损伤机制复杂,涉及到多种信号通路。炎症反应可导致脑功能丧失,抗炎可能是脑出血的潜在治疗措施。已有临床研究证实了抑制炎症反应是一种有效的治疗脑出血的措施[13],为临床工作提供了依据。

在ICU内,AKI是常见的临床综合征,有着较高的发病率和病死率[14-15],AKI随后进展至慢性肾功能不全(chronic kidney disease, CKD),需行连续肾脏替代治疗(continuous renal replacement therapy, CRRT)[16],最后可能会进展为终末期肾病(end stage kidney disease, ESKD)。同时,AKI与患者住院时间延长、住院总花费增加、以及短期和长期死亡等不良结局密切相关。近些年来,大多数研究集中在脓毒症、妊娠、心脏手术与AKI的关系[17-20],形成一些预防和治疗性的措施,对于临床上患者的预后有着重要的作用,目前研究最多的是关于心肾综合征(cardio-renal syndrome, CRS),其主要的发病机制可能与血流动力学、炎症因子以及神经激素等因素相关[21],关于大脑和肾脏之间的机制可能与血管张力和血压的调节有关[22]。有研究表明,卒中患者AKI的发生率为17.4%,此外AKI的发生与患者的病死率密切相关[23]。然而在本研究中表明脑出血患者中AKI的发生率高达29.33%,可能与纳入的人群为重症患者有关,其AKI的发生是预测患者院内死亡的危险因素,临床工作人员应早期识别和预防其进展。

本研究仍有一些不足之处。首先为单中心、回顾性研究,患者数量较少,有待行多中心、前瞻性研究来证实本研究结果。由于回顾性研究中数据不完整的局限性,其他影响患者预后情况的指标尚未考虑到。此外,随访仅限于住院期间,缺乏患者出院后长期随访结果。

| [1] | An SJ, Kim TJ, Yoon BW. Epidemiology, risk factors, and clinical features of intracerebral hemorrhage:an update[J]. J Stroke, 2017, 19(1): 3-10. DOI:10.5853/jos.2016.00864 |

| [2] | Fu X, Wong KS, Wei JW, et al. Factors associated with severity on admission and in-hospital mortality after primary intracerebral hemorrhage in China[J]. Int J Stroke, 2013, 8(2): 73-79. DOI:10.1111/j.1747-4949.2011.00712.x |

| [3] | Ojaghihaghighi S, Vahdati SS, Mikaeilpour A, et al. Comparison of neurological clinical manifestation in patients with hemorrhagic and ischemic stroke[J]. World J Emerg Med, 2017, 8(1): 34-38. DOI:10.5847/wjem.j.1920-8642.2017.01.006 |

| [4] | Kayhanian S, Weerasuriya CK, Rai U, et al. Prognostic value of peripheral leukocyte counts and plasma glucose in intracerebral haemorrhage[J]. J Clin Neurosci, 2017, 41: 50-53. DOI:10.1016/j.jocn.2017.03.032 |

| [5] | Kellum JA, Lameire N. Diagnosis, evaluation, and management of acute kidney injury:a KDIGO summary (Part 1)[J]. Crit Care, 2013, 17(1): 204. DOI:10.1186/cc11454 |

| [6] | Agnihotri S, Czap A, Staff I, et al. Peripheral leukocyte counts and outcomes after intracerebral hemorrhage[J]. J Neuroinflammation, 2011, 8: 160. DOI:10.1186/1742-2094-8-160 |

| [7] | Menegazzi JJ, Davis EA, Sucov AN, et al. Reliability of the Glasgow coma scale when used by emergency physicians and paramedics[J]. J Trauma, 1993, 34(1): 46-48. DOI:10.1097/00005373-199301000-00008 |

| [8] | Poungvarin N, Suwanwela NC, Venketasubramanian N, et al. Grave prognosis on spontaneous intracerebral haemorrhage:GP on STAGE score[J]. J Med Assoc Thai, 2006, 89(Suppl 5): S84-93. |

| [9] | Huang Y, Chen J, Zhong S, et al. Role of APACHE Ⅱ scoring system in the prediction of severity and outcome of acute intracerebral hemorrhage[J]. Int J Neurosci, 2016, 126(11): 1020-1024. DOI:10.3109/00207454.2015.1099099 |

| [10] | He D, Zhang Y, Zhang B, et al. Serum procalcitonin levels are associated with clinical outcome in intracerebral hemorrhage[J]. Cell Mol Neurobiol, 2018, 38(3): 727-733. DOI:10.1007/s10571-017-0538-5 |

| [11] | Löppönen P, Qian C, Tetri S, et al. Predictive value of C-reactive protein for the outcome after primary intracerebral hemorrhage[J]. J Neurosurg, 2014, 121(6): 1374-1379. DOI:10.3171/2014.7.JNS132678 |

| [12] | Di Napoli M, Godoy DA, Campi V, et al. C-reactive protein level measurement improves mortality prediction when added to the spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage score[J]. Stroke, 2011, 42(5): 1230-1236. DOI:10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.604983 |

| [13] | Chen S, Yang Q, Chen G, et al. An update on inflammation in the acute phase of intracerebral hemorrhage[J]. Transl Stroke Res, 2015, 6(1): 4-8. DOI:10.1007/s12975-014-0384-4 |

| [14] | Chertow GM, Burdick E, Honour M, et al. Acute kidney injury, mortality, length of stay, and costs in hospitalized patients[J]. J Am Soc Nephrol, 2005, 16(11): 3365-3370. DOI:10.1681/ASN.2004090740 |

| [15] | 黄曼, 耿婷婷. 急性肾损伤的研究进展[J]. 中华急诊医学杂志, 2017, 26(9): 986-991. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.issn.1671-0282.2017.09.002 |

| [16] | 陈敏华, 孙仁华, 李茜. 传统肾脏替代治疗开始指标在判断重症急性肾损伤患者预后的价值[J]. 中华急诊医学杂志, 2016, 25(2): 182-189. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.issn.1671-0282.2016.02.009 |

| [17] | 廖雪莲, 康焰. 脓毒症所致急性肾损伤的研究进展[J]. 中华重症医学电子杂志, 2017, 3(4): 301-304. DOI:10.3877/cma.j.issn.2096-1537.2017.04.014 |

| [18] | Parikh CR, Puthumana J, Shlipak MG, et al. Relationship of kidney injury biomarkers with long-term cardiovascular outcomes after cardiac surgery[J]. J Am Soc Nephrol, 2017, 28(12): 3699-3707. DOI:10.1681/ASN.2017010055 |

| [19] | Huang C, Chen S. Acute kidney injury during pregnancy and puerperium:a retrospective study in a single center[J]. BMC Nephrol, 2017, 18(1): 146. DOI:10.1186/s12882-017-0551-4 |

| [20] | Zhang WR, Garg AX, Coca SG, et al. Plasma IL-6 and IL-10 concentrations predict aki and long-term mortality in adults after cardiac surgery[J]. J Am Soc Nephrol, 2015, 26(12): 3123-3132. DOI:10.1681/ASN.2014080764 |

| [21] | Braam B, Joles JA, Danishwar AH, et al. Cardiorenal syndrome——current understanding and future perspectives[J]. Nat Rev Nephrol, 2014, 10(1): 48-55. DOI:10.1038/nrneph.2013.250 |

| [22] | Afsar B, Sag AA, Yalcin CE, et al. Brain-kidney cross-talk:Definition and emerging evidence[J]. Eur J Intern Med, 2016, 36: 7-12. DOI:10.1016/j.ejim.2016.07.032 |

| [23] | Tsagalis G, Akrivos T, Alevizaki M, et al. Long-term prognosis of acute kidney injury after first acute stroke[J]. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol, 2009, 4(3): 616-622. DOI:10.2215/CJN.04110808 |

2019, Vol. 28

2019, Vol. 28